The Medieval Vulva: Signs and Symbols of Sexuality in Medieval Pilgrimage

Introduction

Pilgrim badges are wearable tokens of devotion that medieval people would pin to their clothes, like brooches, in order to signal to others that they were pilgrims who had partaken on or completed a journey.

Pilgrimage and Badges: A Brief History

During the Middle Ages, many individuals chose to partake in pilgrimage. Women oftentimes faced more restrictions and barriers than men, both before and on their pilgrimages. They often had to gain permission from male figures around them, whether that be father, husband, or local clergy members.1 There is one thing, a phenomenon born from the tribulations of generations of pilgrims, that unites them—communitas.2 Communitas is essentially a shared sense of community. Communitas constitutes “[a] likeness of lot and intention…converted into commonness of feeling.”3 There are many things that help create this sense of community: hardship, camaraderie, illness, completion of the journey etc.; these are all abstract and “intangible” experiences. One example of a tangible and unifying object specific to pilgrimage are what we know today as pilgrim badges… “[they] were meant to be seen and to be understood.”4

Pilgrim badges were discovered in large quantities in the nineteenth century. The majority of badges have been found in or along the side of rivers. Many pilgrim badges were recognizable as used on specific pilgrimages like the shell of the Compostela. These badges were wearable tokens of devotion that medieval people would pin to their clothes, like brooches, in order to signal to others that they were pilgrims who had partaken on or completed a journey.

Profane (Secular) Vs. Holy (Pious)

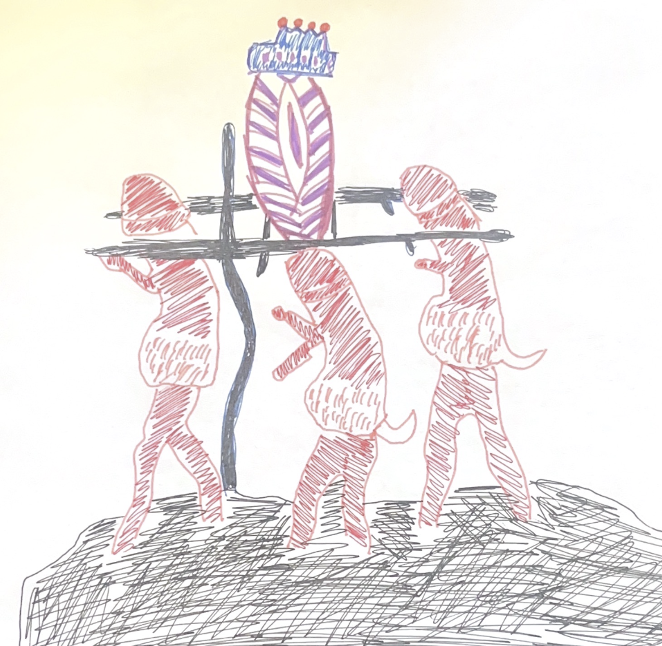

Some of the most enigmatic pilgrim badges to medieval scholars are profane or obscene badges, described this way because of their sexual nature. These profane badges were produced across the fourteenth through sixteenth centuries. Despite being worn on these innately religious pilgrimages, in museum collections they are labeled secular but stored alongside the “holy” badges. The “semantic choice in labeling badges with sexual content as profane and cataloging them alongside sacred pilgrim badges implies that the two types are linked, albeit oppositional.”5 Medieval scholars have debated whether these badges were satirical, making fun of women, or empowering women, and celebrating their sexuality. The profane badges show the vulva both alone and amongst phalluses. The badges range in their content matter; some of the badges show the vulva holding a phallus shaped staff, others show phalluses carrying the vulva in a processional fashion.6

Listen to a podcast on medieval sexuality:

Menstruation in Medieval Society

In the Middle Ages, menstruation was heavily associated with illness, this was related to the main theory of medicinal understanding—humor theory. Humor theory proposed that “[t]he human body was thought to contain a mix of the four humors: black bile (also known as melancholy), yellow or red bile, blood, and phlegm. Each individual had a particular humoral makeup, or “constitution,” and health was defined as the proper humoral balance for that individual. An imbalance of the humors resulted in disease.”7 Thus a period was seen as the body letting go and purifying itself of an excess of blood humor.

Bloodletting was a common practice through which medieval people would pierce skin to let blood pour out: “letting blood was believed to allow the body to reach a healthier balance. How much bleeding was done and where in the body the blood came from could change depending on individual conditions and on the training and beliefs of individual doctors—some of whom took a dangerously extreme approach. Bloodletting was also done seasonally as a tonic.”8 Therefore a periodical release of blood by the body was inherently associated with illness, and “everyone who had a period was in some way diseased.”9 The othering of those who menstruated went as far as “[m]any believ[ing] that anyone who was currently menstruating could make people near them sick. And menstrual blood itself was thought to dull mirrors and even kill crops.”10 This view of menstruation is confusing when we consider that some scholars believe these badges were used to ward off evil and illness.

Women Pilgrims: Exempla but Worthless, and Hysterical

The demand of women to rise beyond the occasion yet remain meek is evident in the writings of friar, preacher, and reformer Felix Fabri, who was a pilgrim to Jerusalem between 1480-1483.11 Fabri writes about six matrons who, as he observed, stuck together during the pilgrimage; his “support for the six matrons was often couched in praise of their displays of humility and meekness. Indeed he even went so far as to favorably compare their quiet behavior to the rowdiness of the male pilgrims.” Fabri’s writings present a view of men towards women as expendable, only comparable to them if they stayed in their predetermined, pre-established lane. Oftentimes that role meant care-giver, one concrete example of this was Fabri’s interpretation of the matron’s caregiving abilities:12

We…cast ourselves down on our beds, very sick; and the number of the sick became so great, that there was no one to wait upon them and furnish them with necessaries. Howbeit, those ancient matrons, seeing our miseries, were moved with compassion, and ministered to us, for there was not one of them that was sick. Herein God, by the strength of these old women, confounded the valor of those knights, who at Venice treated them with scorn, and had been unwilling to sail with them. They moved to and fro throughout the galley from one sick man to another, and ministered to those who had mocked and scorned them as they lay stricken down on their beds.

It was not until the matrons expended themselves beyond measure to care for the men that they were respected, and still Fabri takes a dig at them by calling them ancient. It is these very illnesses towards which badges were thought to offer protection. Thus, this suggests that the imagery of these profane badges, in the medieval mind, might have served more a satirical purpose than an empowering one. If a wandering vulva badge represents the female pilgrim, and the female pilgrim was regarded in this fashion, this leaves little room to believe that the badges were anything but satirical.

Badges Today

Today it is quite rare to find someone wearing a badge but pins are in use. Often pins are attached to backpacks and other bags but sometimes they are worn on clothing, like brooches. Many of these pins are used to signify solidarity with a cause or aspects of one’s own identity like these pronoun badges made at the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center.

You can also buy reproductions of medieval pilgrims’ badges today:

Bibliography

Craig, Leigh Ann. Wandering Women and Holy Matrons: Women as Pilgrims in the Later Middle Ages. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2009.

Hinds, Sarah. “Late medieval sexual badges as sexual signifiers.” Medieval Feminist Forum 55, no. 2 (2020): 170-191. https://doi.org/10.17077/1536-8742.2224.

“Humoral Theory.” Contagion – CURIOSity Digital Collections. Harvard Library. Accessed June 1st, 2024. curiosity.lib.harvard.edu/contagion/feature/humoral-theory.

Koldeweij, Jos. “Shameless and Naked Images: Obscene Badges as Parodies of Popular Devotion.” In Art and Architecture of Late Medieval Pilgrimage in Northern Europe and the British Isles, edited by Rita Tekippe and Sarah Blick. Boston and Leiden: Brill, 2005.

Rasmussen, Ann Marie. Medieval Badges: Their Wearers and Their Worlds. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021.

Turner, Victor W., and Edith L. B. Turner. Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 1978.

Waldorf, Sarah, and Larisa Grollemond. “Getting Your Period in the Middle Ages.” Getty News, J. Paul Getty Trust. Last modified May 4th, 2024, www.getty.edu/news/education-periods-facts-women-medieval-history-past-before-pads-tampons/.

Image Credits

Header image. Drawing by author of a medieval badge showing three phalluses carrying a vulva in a procession.

Fig. 1. Shell from a Santiago de Compostela pilgrim, Paris (found), ca. 1000-1400, now at the Musée Carnavalet, Histoire de Paris (inventory no. AY99/2). Source: Musée Carnavalet, Histoire de Paris, https://www.parismuseescollections.paris.fr/fr/musee-carnavalet/oeuvres/coquille-saint-jacques-de-pelerin#infos-principales. Licensed under Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Deed.

Fig. 2. Pilgrim’s Badge of the Shrine of St. Thomas Becket at Canterbury, Canterbury, England (made), 1350-1400. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/473470. Public domain.

Fig. 3. Reproduction of a fourteenth-century brooch. Photograph by user “Serial Number 54129”, July 28, 2019. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Photograph_of_a_reproduction_of_a_14th-century_brooch.jpg. Licensed under Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0 Deed.

Fig. 4. Pilgrim badge with the Virgin and Christ Child, Germany (found), 13th century. Photograph by user “Daderot”, January 31, 2016. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pilgrim_token,_found_at_Hagenmarkt,_Braunschweig,_early_13th_century_AD,_tin,_lead_-_Braunschweigisches_Landesmuseum_-_DSC04581.JPG. Licensed under Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Deed.

Fig. 5. Illuminated initial ‘N’ with scene of bloodletting, Li Livres dou Santé., France, late 13th century. London: British Library Sloane 2435, fol. 11v. Source: British Library Images, https://imagesonline.bl.uk/asset/4887/. Courtesy British Library.

Fig. 6. Student wearing pronoun pins made at the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center. Photograph by author.

Fig. 7. One of the search results for vulva pilgrim badges (reproductions) on Etsy, listed on the Etsy Shop, PeraPeris. Screenshot, June 28, 2024. Source: Etsy, https://www.etsy.com/uk/listing/1484088781/crude-erotic-medieval-pilgrim-badge?ga_order=most_relevant&ga_search_type=all&ga_view_type=gallery&ga_search_query=vulva+pilgrim+badge&ref=sr_gallery-1-1&content_source=36b8f06c0b6ae7b2efaf23b2a5e8c1166d0932b8%253A1484088781&search_preloaded_img=1&organic_search_click=1.

Fig. 8. One of the search results for vulva pilgrim badges (reproductions) on Etsy, listed on the Etsy Shop, LembergShop. Screenshot, June 28, 2024. Source: Etsy, https://www.etsy.com/uk/listing/996531810/shameless-medieval-pilgrim-badge?ga_order=most_relevant&ga_search_type=all&ga_view_type=gallery&ga_search_query=vulva+medieval+pilgrim+badge&ref=sr_gallery-1-2&sca=1&ret=1&content_source=595e77b2a14d1163ce116b9f9bb857223d702cca%253A996531810&search_preloaded_img=1&organic_search_click=1.

Fig. 9. One of the search results for vulva pilgrim badges (reproductions) on Etsy, listed on the Etsy Shop, GypsyKingArmor. Screenshot, June 28, 2024. Source: Etsy, https://www.etsy.com/uk/listing/603698697/medieval-times-badges-hunting-vagina?ga_order=most_relevant&ga_search_type=all&ga_view_type=gallery&ga_search_query=vulva+medieval+pilgrim+badge&ref=sr_gallery-1-31&pro=1&sca=1&ret=1&content_source=4c9581d68c16d9264da6af2afbc896978f3448db%253A603698697&search_preloaded_img=1&organic_search_click=1.

The Author

Betsy Subiros is an Art History and Queer Studies double major at Vassar College who is interested in exploring the gender line in medieval life and pilgrimage.