Thomas Becket Badges: Developments and Interpretations of His Cult since the Twelfth Century

Introduction

Thomas Becket (1120–70) was an archbishop, martyr, and saint. He is one of the most researched men from the Middle Ages. Badges of him, which have been discovered in abundance, not only attest to his cult but also help us understand and evaluate the vibrant developments of art and literature about the pilgrimage to Canterbury. Various interpretations of these badges have been made by Jennifer Lee, Kay Slocum, and Hanneke Van Asperen, in terms of their production, consumption, and distribution.

The Martyrdom of Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Becket

Little is known about the early life of Thomas Becket, but apparently when he was young he was introduced, possibly by his father, to Theobald, who preceded him as archbishop of Canterbury. He possessed knowledge of the canon law that governed the Catholic Church, and, with Theobald’s support, was promoted to royal chancellor to Henry II in 1155, when he was 34 or 35 years old. Becket’s appointment as archbishop of Canterbury six years later was a watershed in his relationship with the king; they became hostile to each other thereafter. Indeed, Becket’s conflicting attitudes have long been a subject of debate. However, it is clear that the royal court wanted to exert more control over the ecclesiastical court, but to no avail.1 The archbishop soon abandoned his role as the king’s chancellor, but the king brought the case to court. Becket was declared guilty and exiled from England in 1164. Yet, his years of exile gave him the opportunity to follow an ascetic life, and he was not alone. Pope Alexander III and Louis VII of France sided with Becket and they negotiated with Henry II, who was increasingly concerned about the formality of passing the crown to his son, Philip II, whose coronation was held without the archbishop, but rather with the bishops of York and London, who were excommunicated as a result of their breach of duty.

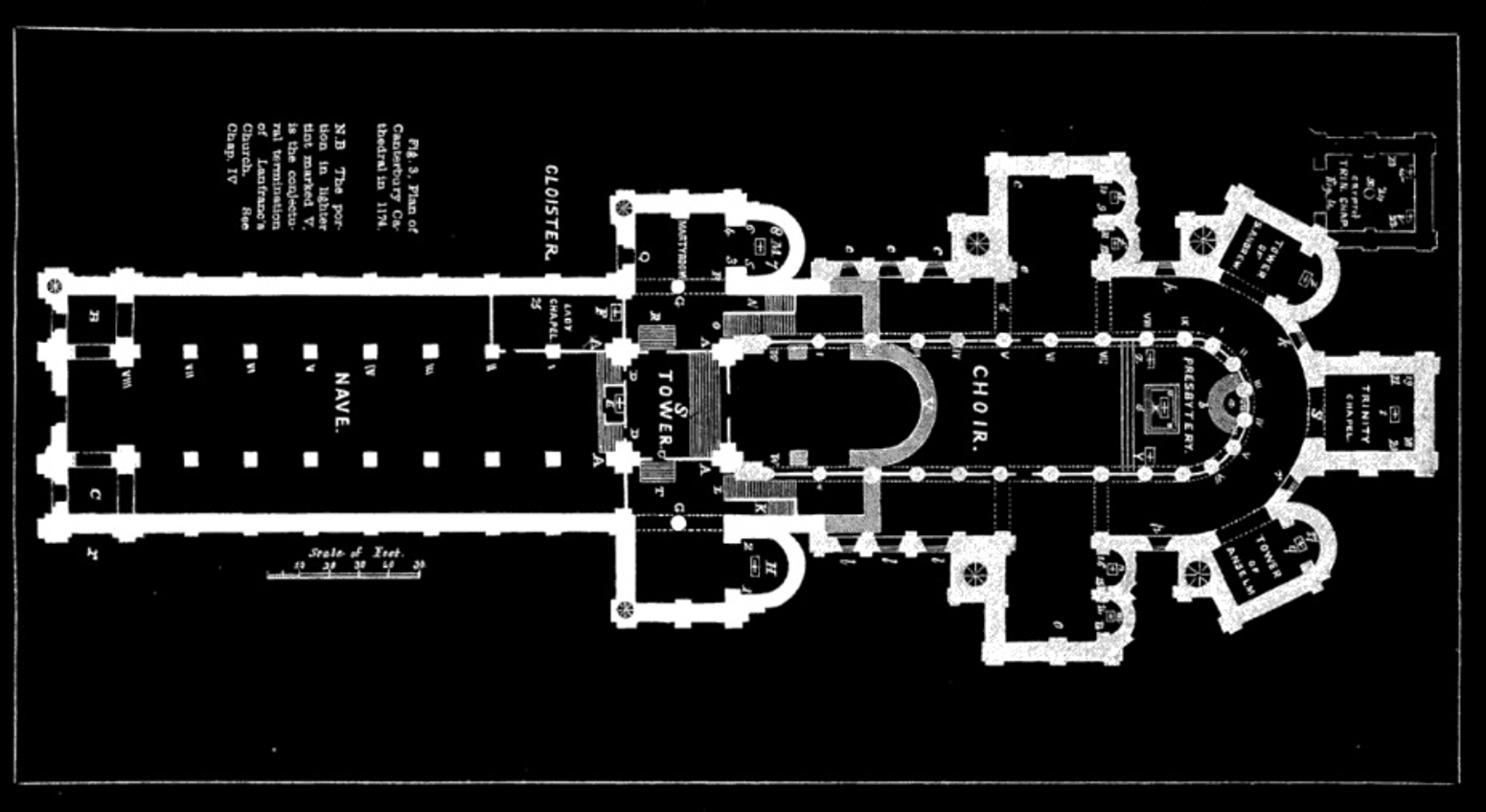

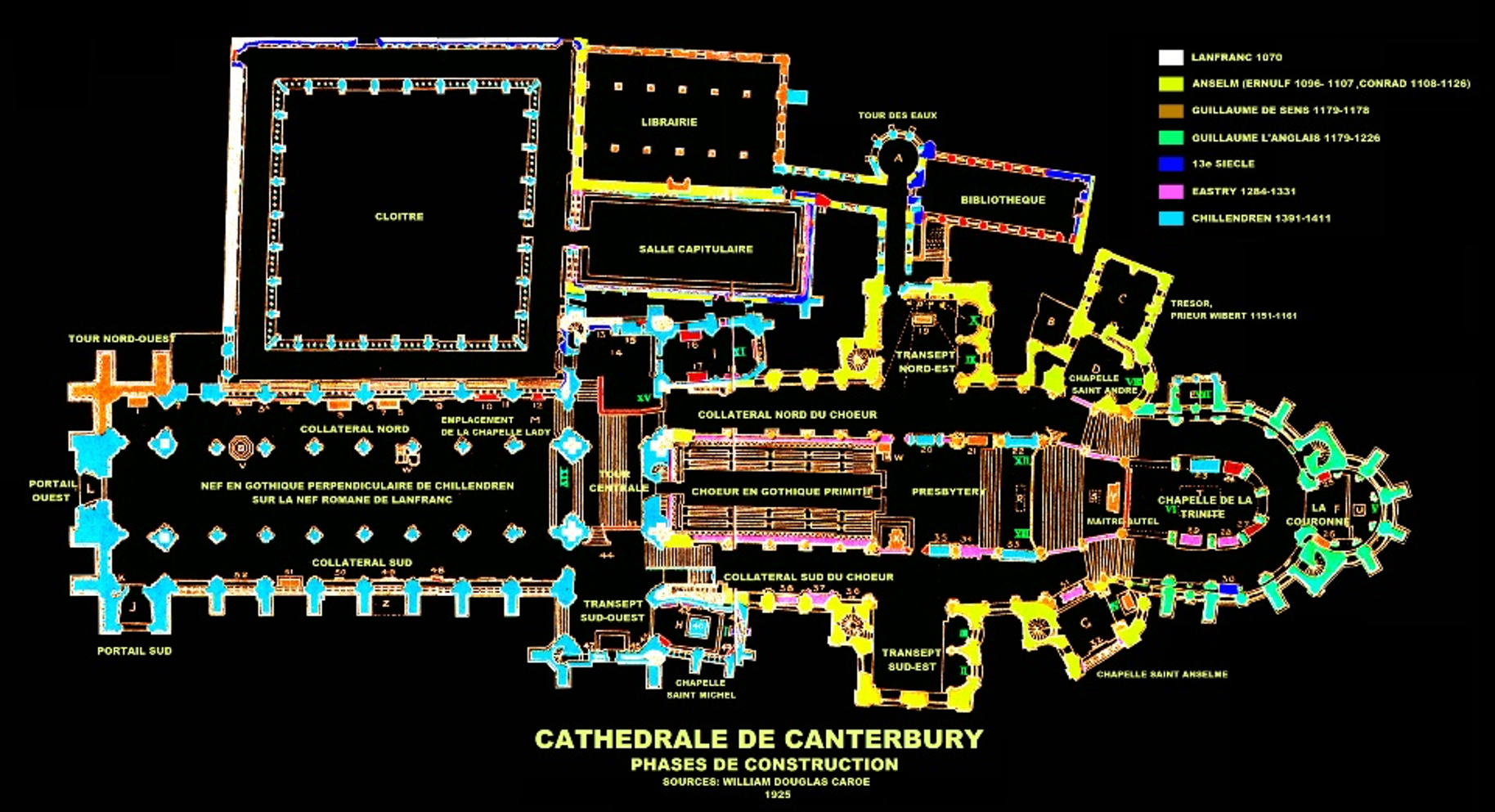

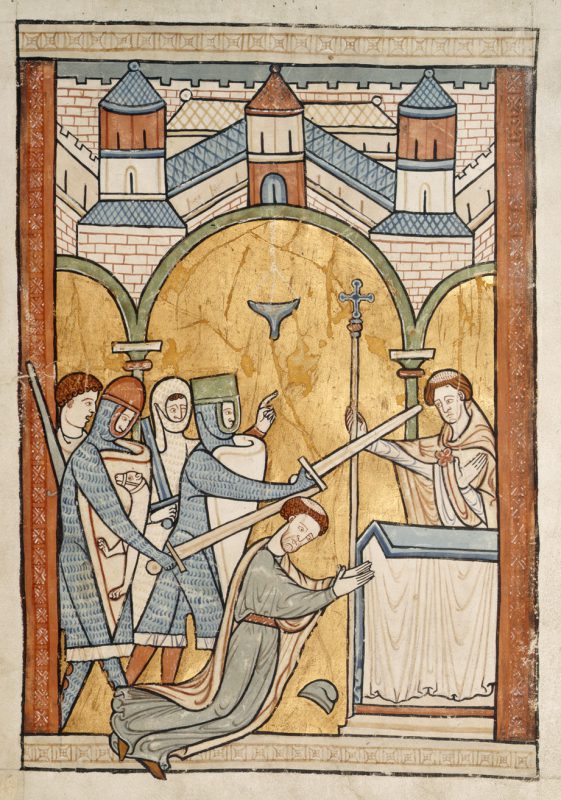

The king finally agreed to Becket’s return in 1170; however, it was a short-lived “armistice.” Disputes between the crown and the churches of England could not be resolved. Toward the end of the same year, on December 29th, four knights of the king—Hugh de Morville, Reginald Fitzurse, Richard le Bret, and William de Tracy—staged the assassination of Becket at his cathedral during the singing of vespers (fig. 1a-b). A priest, Edward Grim, tried to stop the knights but was injured. It is believed that the archbishop adopted a submissive pose when he knew that he would be killed and that Fitzurse made the fatal blow. His death was shocking. Consequently, Henry II did public penance, walking barefoot from Saint Dunstan’s Church to Canterbury Cathedral, and upon arrival asked the monks to flog him. The cathedral was closed the following year. When it reopened, it was flooded with pilgrims who went to see Becket’s tomb in the crypt. In 1173 Becket was canonized, and Canterbury Cathedral officially became his shrine.

The Cult of Saint Thomas Becket

Miracles were reported immediately after the martyrdom of Thomas Becket, notably by the monks Benedict of Peterborough and William of Canterbury. The saint was known to cure many illnesses: Benedict notes that Edilda and Wlviva resumed the ability to walk; Edmund of Canterbury, Robert from the Isle of Thanet, and Henry of Fordwich regained their eyesight; Muriel and Agnes were rescued from death; Ethelburga’s shoulder pain was relieved; and Eilward of Tenham recovered his sense of smell, all of which were associated with Becket, as they had all visited his cathedral.2 Pilgrims with health issues were motivated to go on a pilgrimage to Canterbury.

Between the thirteenth and mid-sixteenth centuries, the cult of Becket continued to grow, and he appeared frequently in art and literature. Apart from manuscript illustrations of his martyrdom (the header image) and the collections of his miracles, Becket was portrayed in wall paintings, mosaics, and enamel works, as well as written about in biographies and popular tales and poems, such as William Langland’s Piers Plowsman (1367–86) and Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales (1387–1400). The latter are both satires of the decline of morality surrounding the life of pilgrims. Though unfinished, The Canterbury Tales is a detailed account of a group of thirty pilgrims from all walks of life who meet in a hospice. Together with their host, they form a community of faith, but rather than showing how religious they are, the book tells who they were in terms of occupation. In addition to the clergymen, the group was composed of a knight, a merchant, a sergeant, a doctor, a woman from Bath, a pardoner, landowners, officials, farmers, and other commoners.3 This demonstrates the complexity of pilgrimage in the late medieval period. The vast array of art and literature on the pilgrimage to Canterbury marks Becket’s growing popularity. However, his cult was put to an end in 1538, when Henry VIII ordered the destruction of his shrine. The king attacked not only the living shrine, but also the dead Becket, for the king blamed him for his own martyrdom, claiming that Becket had broken with the Catholic Church. This was the golden age of the Counter-Reformation.

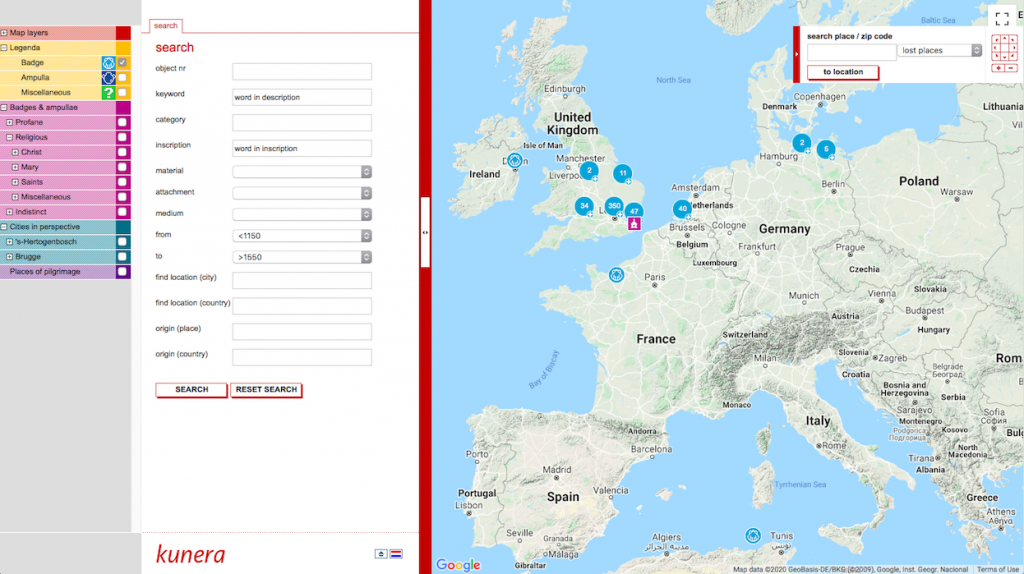

[Guide for using the map: *To see the labelled map, select “Saints” (under “Badges & ampullae”) in the dropdown menu on the left. Then, scroll down and select “Thomas Becket, Canterbury”. **To switch between Dutch and English, click on the flag icon on the bottom right corner in the white column.]

A Preliminary Typology of Thomas Becket Badges

The cult of Thomas Becket went underground during the reign of Henry VIII. It later revived, and he is still venerated as a saint today. Becket’s cult peaked in the late Middle Ages. When Canterbury Cathedral came to prominence across the continent as a sacred site, it was already a common practice for pilgrims to bring home souvenirs. They held commercial value as a source of income for the churches. Souvenirs could also be considered an alternative to relics and reliquaries, and thus they protected the precious relics from the craze for sanctity. The traditional view is that one can be purified through contact with relics, but at that time pilgrims also had the compulsion to take away pieces, if not the whole item—that is to say, they desired possession. Ampullae were the prototype, which was gradually replaced by badges. As Kay Slocum suggests, ampullae were both practical and beautiful, whereas badges were solely an emblem of one’s relationship with the saint (as in figs. 3–8, where Becket is symbolized rather than depicted); the faithful thus favored badges.4

The Becket badges described in this essay can be found at the British Library, Museum of London, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art and mostly date to the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. It was only in the mid-twentieth century that archaeologists, with the aid of metal detectors, unearthed a large number of badges, and historians like Beuningen, Koldeweij, and Spencer facilitated dating. As shown in figure 2, Becket badges came from northern and western parts of Europe, in what is now England, Scotland, Ireland, Denmark, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany. A few were found in faraway Poland. The majority of them were discovered in waterways; for instance, hundreds were excavated from the River Thames in London. Scholars have proposed several reasons for their provenance: they were scattered because badges were dumped and recycled into other metal works in whatever destination they reached, and they were deposited in rivers because it was a ritual for pilgrims to break the badges and throw them into water as wishes or as gestures of thanksgiving.5 These explanations are not satisfactory without evidence and require further research. Nevertheless, Becket badges are traces of his far-reaching cult, both temporally and geographically, and their iconography tells appealing stories.

Becket badges are plentiful and below I will attempt to extract some common types that can be used as models for identifying these badges in general. Figure 3 is an example of the first type. It shows only a bust of Becket, who wears the pointed miter and chasuble, liturgical vestments characteristic of a bishop (compare this with fig. 5a, in which the archbishop is depicted head to toe, and in addition to miter and chasuble holds a hooked crozier). Figure 3 is a stable and straightforward representation of the saint, which was often depicted. It correlates highly in form with the reliquary bust once displayed in the Corona Chapel at Canterbury Cathedral, which was used to house the martyr’s skull.

Figure 4a–c demonstrates the second type. It emerged from the first type, but here the bust is framed and the frame inscribed. Figure 4a adopts an architectural frame, and the inscription on the base. “an:th,” means Saint Thomas. Like a coin, figure 4b bounds Becket’s bust in a circular frame, which was indeed a conventional design of late medieval badges. The frame of figure 4c is wavy, protruding like a star and much more sophisticated than figure 4b. Openwork niches were added to the empty space flanking Becket, and “+ SANCTVS THOMAS,” inscribed clockwise on the frame, also means Saint Thomas. It was believed that inscriptions rendered the badges more protective.

Figure 5a–c shows the third type and depicts full-scale, standing figures tied to a particular event in Becket’s life. In figure 5a, Becket is holding a mass, while in figure 5b he is riding a horse oriented toward the west, which signifies his return from exile in France. This iconography resembles that of Christ’s triumphal entry to Jerusalem. Figure 5c depicts the martyrdom of Becket. Henry II’s knights are packed into a rectangular frame. Their shields are shown frontally and have different patterns, and hence they are tools for identification.

The fourth type of Becket badge departs from the first three types in that it no longer uses bodily forms but rather simple symbols, such as the bell, sheath (fig. 6a), sword (fig. 6b-d), and a pair of gloves (fig. 7). These symbols are reductive but meaningful as the key attributes of Becket’s martyrdom, and they perfectly match the defining characteristics of badges—they are recognizable, portable, and intended for long-time wear. Badges made in the form of a bell are reminiscent of the miraculous ringing of all bells in Canterbury Cathedral when Fitzurse took Becket’s life and reminded pilgrims of their own aural experience of pilgrimage to Canterbury. As described in The Canterbury Tales, on the way to Becket’s shrine pilgrims sang and there were many other sounds. Sound is also emitted from the movement of the actual bells sold as souvenirs.

The swords, sheaths, and shields used by Becket’s assailants are contact relics and were transformed into badges in miniature. Usually, the sword and sheath were made in pairs. Often, however, either the sword or the sheath has been lost, as one can observe in figure 6a and figure 6b, respectively. Like figure 6b, figure 6c and figure 6d represent the sword that killed Becket beneath large circular shields. We can still see the tip and quillon of the sword in figure 6c, whereas the sword in figure 6d is completely obscured.

The fifth and final type of Becket badge is the most difficult to characterize, for it narrates an imaginative story that took place at Canterbury Cathedral. Figure 8a shows the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ on a central throne, Becket to their left and a king to their right, all inside the shrine of Our Lady Undercroft. Similarly, in figure 8b Becket is depicted in his tomb, which is gilded and decorated with jewels, including the then largest ruby, with two ships flanking its sides.

Making, Using, and Keeping Badges in the Middle Ages

It is rare to find a delicate medieval badge. Most of them were coarsely produced using a casting technique: the craftsperson poured liquefied metal alloy, often lead mixed with tin or pewter, into a mold, and when the metal solidified, the mold was removed and the wasted pieces broken off. This 3-D model is an example of a stone mold and is only one of the two halves needed to hold the materials in shape. Its design looks like that of figure 5b, Becket on horseback, but this example has a richer background. Supposedly, the other half was cut with another design for the back of the badge or, as demonstrated in the video, it was split into another two halves that completed the pin and catch. Since these raw materials were cheap and readily accessible, casting was easy, and pilgrims could afford to buy them regardless of their wealth. They then often sewed their badges onto hats, coats, and bags. There were also expensive copies that necessitated finer craftsmanship. For example, figure 8b, Becket’s tomb, was made by the famed goldsmith Walter of Colchester.

Becket on horseback mold, England, fourteenth century, stone, 97 x 85 x 24 mm, © The Trustees of the British Museum

“Making a Medieval Pilgrim Souvenir,” © Digital Pilgrim.

As mentioned above, badges were souvenirs to commemorate one’s pilgrimage to a holy site. They could also be votive offerings for blessings or used as tokens of appreciation, amulets to protect pilgrims on their return trips, and gifts for dear friends or relatives. Hanneke Van Asperen expands on another function of badges: as bookmarks kept in prayer books.6 There is evidence of such use with Thomas Becket badges, offsets of which are left on pages of manuscripts dedicated to prayers to the saint. In one such manuscript, coin-shaped badges like figure 4b were found, which are exemplary of what Van Asperen argues—that the book itself was a treasure chest. In sum, badges in books of hours served dual purposes, practically as bookmarks and spiritually as the visualization of tools for pilgrims to take a mental journey to the holy site and to the saint.

Bibliography

Blick, Sarah. “Votives, Images, Interaction and Pilgrimage to the Tomb and Shrine of St. Thomas Becket, Canterbury Cathedral.” In Push Me, Pull Me: Imaginative, Emotional, Physical, and Spatial Interaction in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art, edited by Sarah Blick and Laura Gelfand, 21–58. Leiden: Brill, 2011.

“British Museum.” Sketchfab. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://sketchfab.com/britishmuseum/collections/digital-pilgrim.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Canterbury Tales. Champaign: Project Gutenberg, 2000. http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/2383/pg2383-images.html.

Davies, Horton, and Marie-Hélène Davies. “The Motivations of Pilgrimage.” In Holy Days and Holidays, edited by Horton and Marie-Hélène Davies, 17–41. London: Associated University Press, 1982.

Jeffs, Amy, and Gabriel Byng. “The Digital Pilgrim Project: 3D Modeling and GIS Mapping Medieval Badges at the British Museum.” Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 6, no. 2 (2017): 80–90.

Lee, Jennifer. “Medieval Pilgrims’ Badges in Rivers: The Curious History of a Non-Theory.” Journal of Art Historiography 11, no. 1 (December 2014): 1–11.

———. “Signs Of Affinity: Canterbury Pilgrims’ Signs Contextualized, 1171–538.” PhD diss., Emory University, 2003.

“Medieval Pilgrim Souvenirs.” Museum of London. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/online/group/19998.html.

Ostkamp, Sebastiaan. “The World Upside Down, Secular Badges and the Iconography of the Late Medieval Period: Ordinary Pins with Multiple Meanings.” Journal of Archaeology in the Low Countries 5, no. 1 (November 2009): 1–2.

Simonsen, Margrete Figenschou. “Medieval Pilgrim Badges: Souvenirs or Valuable Charismatic Objects?” In Charismatic Objects: From Roman Times to the Middle Ages, edited by Marianne Vedeler, Ingunn M. Røstad, et al, 169–96. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk, 2019.

Slocum, Kay Brainerd. The Cult of Thomas Becket: History and Historiography through Eight Centuries. Oxon: Routledge, 2019.

“The Met Collection.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection.

Van Asperen, Hanneke. “The Book as Shrine, the Badge as Bookmark: Religious Badges and Pilgrims’ Souvenirs in Devotional Manuscripts.” In Domestic Devotions in the Early Modern World, edited by Marco Faini and Alessia Meneghin, 288–312. Leiden: Brill, 2018.

“Virtual Tour.” Canterbury Cathedral. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.canterbury-cathedral.org/virtual-tour/.

Whalen, Brett Edward. Pilgrimage in the Middle Ages: A Reader. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011.“William Langland, Piers Plowman.” British Library. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.bl.uk/learning/timeline/item126920.html.

Image Credits

Header. Martyrdom of Thomas Becket – Psalter (c.1220), f.32 – BL Harley MS 5102. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Martyrdom_of_Thomas_Becket_-_Psalter_(c.1220),_f.32_-_BL_Harley_MS_5102.jpg#/media/File:Martyrdom_of_Thomas_Becket_-_Psalter_(c.1220),_f.32_-_BL_Harley_MS_5102.jpg. Cropped image licensed under CC0 1.0 (Universal Public Domain Dedication).

Fig. 1a. Plan of Canterbury Cathedral, reconstructed after a fire in 1174 burnt down the choir, 1174, from Robert Willis, The Architectural History of Canterbury Cathedral (London: Longman & Co., 1845), p.38, digitalized by Google Books, Nov 27, 2006. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Plans_of_Canterbury_Cathedral#/media/File:Canterbury_Cathedral_1174b.png. Modified image in the public domain.

Fig. 1b. Plan of Canterbury Cathedral, with phases of construction, modified from the original by William Dougla Caroe (1857-1938). Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Plans_of_Canterbury_Cathedral#/media/File:Canterbury1925.png, modified image licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Fig. 2. Map of digitalized pilgrim badges and ampullae from the late medieval period, those related to Becket are labeled. Credit: Kunera, https://www.kunera.nl/Kunerapage.aspx. Permission to use image granted by Kunera.

Fig. 3. Pilgrim badge of Becket’s bust, c.1320-1375, Canterbury, Kent. British Museum number: 2001,0702.1, © The Trustees of the British Museum. Source: The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_2001-0702-1, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Fig. 4a. Pilgrim badge of Becket’s bust, late 14th-15th century, Canterbury, lead alloy, 83 x 45 mm. Museum of London ID: 97.95/2, © Museum of London. Source: Museum of London, https://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/online/object/290893.html. Fair dealing of image for non-commercial research.

Fig. 4b. Pilgrim badge of Becket’s bust, 15th century, Canterbury, tin-lead alloy, 24 x 2 mm. The Cloisters Collection, 1986. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Accession Number: 1986.77.4, © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/469970. Public domain.

Fig. 4c. Pilgrim badge of Becket’s bust, 14th century, Canterbury, tin-lead alloy, 60 x 71 mm. Museum of London ID: 8784, © Museum of London. Source: Museum of London, https://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/online/object/37239.html. Fair dealing of image for non-commercial research.

Fig. 5a. Pilgrim badge of Becket, early-mid-15th century, Canterbury, lead alloy, 96 x 25 mm. Museum of London ID: 86.202/13, © Museum of London. Source: Museum of London, https://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/online/object/29245.html. Fair dealing of image for non-commercial research.

Fig. 5b. Pilgrim badge of Becket on horseback, 14th-15th century, Canterbury, lead alloy, 100 x 80 x 3 mm. Museum of London ID: A24766/1, © Museum of London. Source: Museum of London, https://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/online/object/37282.html. Fair dealing of image for non-commercial research.

Fig. 5c. Pilgrim badge of the knights, mid-late 14th century, Canterbury, lead alloy, 35 x 30 mm. Museum of London ID: 82.255/3, © Museum of London. Source: Museum of London, https://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/online/object/29279.html. Fair dealing of image for non-commercial research.

Fig. 6a. Pilgrim badge of a hollow sheath, c.1350-1450, possibly made in England, 97.48 x 18.63 mm. British Museum number: OA. 1817, © The Trustees of the British Museum. Source: The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_OA-1817, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Fig. 6b. Pilgrim badge of the sword, 14th-15th century, Canterbury, lead alloy, 84 x 24 mm. Museum of London ID: 79.135/4, © Museum of London. Source: Museum of London, https://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/online/object/29374.html. Fair dealing of image for non-commercial research.

Fig. 6c. Pilgrim badge of the sword and the shield, 14th century, Canterbury, lead alloy, 62 mm. Museum of London ID: 80.154/1, © Museum of London. Source: Museum of London, https://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/online/object/28777.html. Fair dealing of image for non-commercial research.

Fig. 6d. Pilgrim badge of the sword and the shield, 14th century, Canterbury, lead alloy, 57 x 10 mm. Museum of London ID: O2194, © Museum of London. Source: Museum of London, https://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/online/object/32122.html. Fair dealing of image for non-commercial research.

Fig. 7. Pilgrim badge of Becket’s gloves, 15th century, Bury St Edmunds, England, tin-pewter alloy, 30 x 26 x 6 mm. Gift of William and Toni Conte, 2002. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Accession Number: 2002.306.20, © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/474382?searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&ft=British%2c+Canterbury&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=13. Public domain.

Fig. 8a. Pilgrim badge of Mary, Christ, Becket and a king in the shrine of Our Lady Undercroft, late 14th century, Canterbury, lead alloy, 121 x 71 mm. Museum of London ID: 84.394, © Museum of London. Source: Museum of London, https://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/online/object/29153.html. Fair dealing of image for non-commercial research.

Fig. 8b. Pilgrim badge of Becket’s tomb, made by Walter of Colchester, 1350–1400, Canterbury, tin-lead alloy, 79 x 64 x 3 mm. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. W. Conte, 2001. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Accession Number: 2001.310, © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/473470. Public Domain.

The Author

Jane Chan is a BA candidate at the University of Hong Kong, as well as a recipient of the UOB Scholarship in Fine Arts. She has a broad interest in the history of art and architecture, spanning from works in Asia to those in Europe and America; recently, she has also been introduced to digital humanities. This is the first time she has researched popular medieval pilgrimage routes, particularly those leading to Canterbury.