Chartres Cathedral: Pilgrimage to the Sainte Chemise

Introduction

Located about 50 miles outside of Paris, Chartres Cathedral is a site with a long history of destruction and reconstruction. The most famous example of this would be in September of 1194 when a large fire burned down most of the building. All that survived was the west facade, the two towers, the crypt, and, miraculously, the relic of the Sainte Chemise: the undergarment said to have been worn by the Virgin Mary when she gave birth to the Christ Child.

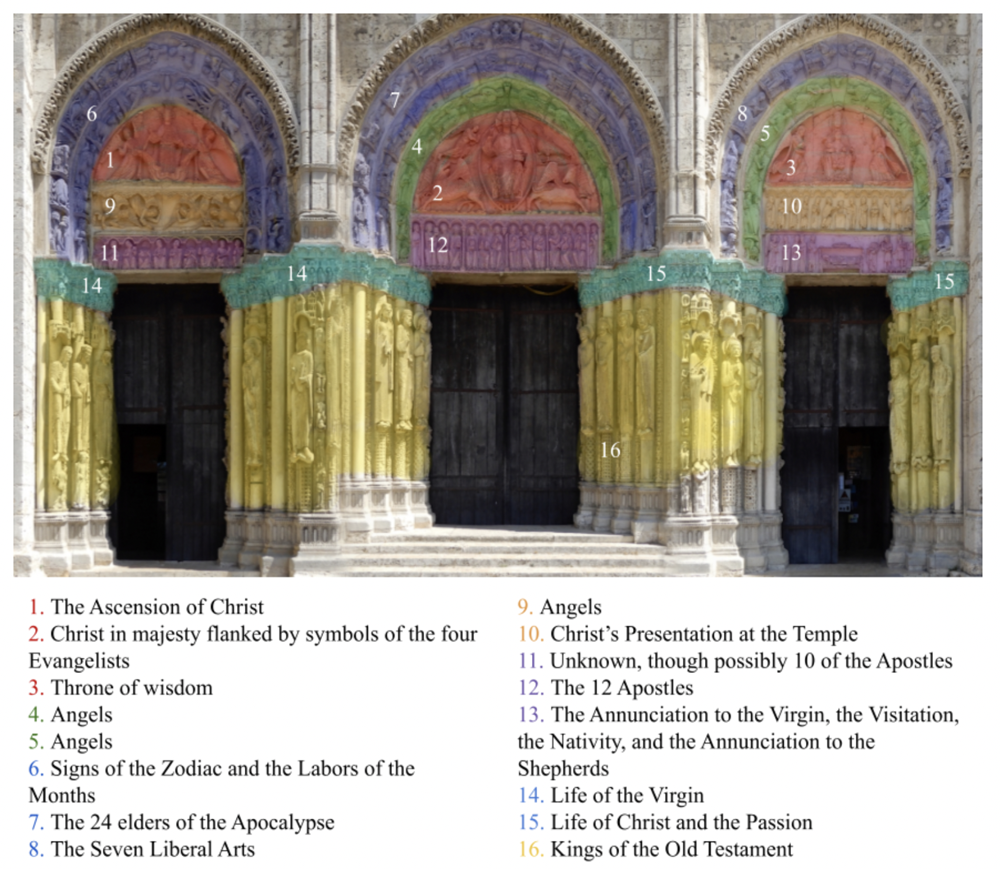

For three days after the fire, the Chemise was thought to have been tragically destroyed; however, the cathedral chapter soon learned that a few priests had been able to sneak it out the back of the crypt at the last minute.1 Though the relic had already garnered attention from pilgrims, the institution wanted to capitalize off of this early miracle and frame the cathedral specifically as a site of pilgrimage. They built the Gothic structure that we know so well today with its basilica plan, a wide double-aisled ambulatory, and many radiating chapels.2 This design would allow large numbers of pilgrims close access to relics without interrupting masses at the altar. The 1194 miracle also led to Chartres making Mary the patron saint of the cathedral, bringing with this a plethora of Marian imagery to greet pilgrims.3 Today, approximately 175 different representations of the Virgin can be found throughout the cathedral.4

The Sainte Chemise

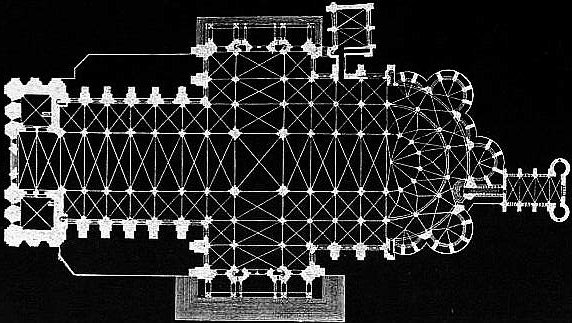

While the Sainte Chemise’s popularity grew as a result of late medieval pilgrimages to Chartres, it had a rich history predating the 1194 fire. Today it seems clear that the relic was a gift from Holy Roman Emperor Charles the Bald in 876.5 However, popular legend at the time held that the relic was given to the cathedral by Charlemagne, who obtained it during a supposed campaign to the Holy Land.6 This narrative is told in the Charlemagne stained glass window. In one panel, he is shown crowned and kneeling before an altar, presenting a monk with his crusade spoils. This imagery acts as a way to authenticate the chemise. It relates the relic to the power of the first Holy Roman Emperor and validates its ownership by the cathedral. And this was certainly an important relic for Chartres to claim. The Virgin did not leave bodily relics when she died, the way other saints did. She was said to have been assumed into heaven by God after her death, and her heavenly enthronement left no physical body behind on earth.7 Certain corporeal relics of hers did become popular, like breast milk or blood, although contact relics like the chemise were the primary means of building a material connection to the Virgin.8

Pilgrims’ Badges from Chartres

One place where the mass interest in the Sainte Chemise becomes clear is through imagery of the tunic on pilgrims’ badges. The most common badges were double-sided: one side featuring the chemise and the other the Virgin and Child. These badges were given a rather architectural shape, with a central nave and two aisles represented by arches along the top. Centered on the front is the chemise in a simplified geometric cutout shape. In many badges, the tunic is shown being carried by men on either side in a famous procession that was a popular attraction for pilgrims.9 Interestingly enough, the Virgin and Child on the reverse are also shown in procession, signifying potentially a representation of a lost Romanesque sculpture of the Throne of Wisdom that would often have been carried in procession alongside the tunic.10 Giving so much precedence to imagery of relics as opposed to the actual bodily presence of the Virgin was somewhat unusual for a French pilgrim’s badge.11 Later badges sold at Chartres would even be simplified to just a small chemise worn as a pendant around the neck, which are often called chemisettes.12 It is easy to imagine the significance of wearing imagery of these relics on your body at all times and carrying the Virgin Mary’s divine protection with you.

Because the Virgin lacked bodily relics and the Sainte Chemise’s power already relied on its close contact with her body, contact relics from Chartres were seen as particularly potent.13 Wealthy people would buy their own tunics that they would touch to the chemise reliquary to then wear under their own clothes.14 There are even many miracle stories from Chartres that are attributed to these replica chemises. For those who could not afford these textiles, a pilgrim’s badge served as the next best thing. While some badges were made of precious metals for the wealthy, most were mass-produced and cheaply made of tin or lead, making them accessible to a wide range of pilgrims.15 But these inexpensive items still gained strong meaning both as contact relics and as memory aids of a meaningful pilgrimage.

Depiction of Mary on the Western Portal

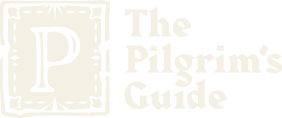

Another place where Marian imagery greets pilgrims at Chartres is on the west portal, the cathedral’s main entrance for visitors. Built in the mid-twelfth century, this was one of the few parts of the cathedral to survive the 1194 fire and today stands as a major example of early Gothic architecture.16 The main sculptures on the portal’s three tympana are what one might expect from a Gothic Cathedral: Christ in Majesty at the center, flanked by the Ascension of Christ above the northern portal and the Infancy of Christ above the southern. However, it is in the long narrative frieze that lines the column capitals where a less common narrative of the Virgin Mary’s life is told. The story begins with Mary’s parents Anne and Joachim struggling with infertility and their prayers being answered as the angel announces that Anne would soon conceive. Following this we see the bath of the Virgin (imagery that would often replace scenes of her birth)17 and simple family scenes with little biblical significance. The narrative then follows her youth up until when she is presented to her husband Joseph. This strong emphasis on family is still at the core of the narrative on the other side of the frieze, which depicts the life of the Christ Child. In the scene of the Annunciation, which would typically only need to include the Virgin, Joseph is shown sitting by her side, creating a familial scene.

Chartres attracted many female pilgrims, and the scenes of family and Mary as the epitome of perfect motherhood were likely expected to resonate for these women viewers. Many of the Sainte Chemise’s miracle stories tell of mothers coming to pray for the safety of their children, with stories of babies drowning and swallowing glass only to be miraculously revived in the presence of the Virgin at Chartres.18 Additionally, many women would have come to Chartres to pray for safety in childbirth. Wealthy and royal women would even buy replica tunics, which they touched to the reliquary of the Sainte Chemise and would later wear while giving birth.19 But despite all of this, the imagery of family on the west facade is not entirely positive for female pilgrims. Mary becomes the pinnacle of perfect motherhood for these women to aspire to, though it is a sort of divine perfection as both ideal mother and virgin that would always be out of reach for even the most devout pilgrims. This sort of imagery complicates medieval female devotion, making true salvation seem just out of reach.

Mary also appears on the southern tympanum of the west portal. At the center of scenes of his young life, the Christ Child is shown in the lap of the Virgin Mary. Flanked by angels on either side, the Virgin and Child sit frontally in a rather stoic position. This sort of Marian imagery is referred to as the Throne of Wisdom as Mary acts as a throne for the Christ Child and his Divine Wisdom.20 At times referred to as the Virgin and Child in Majesty, she is shown as exactly that – in majesty – embodying her enthronement as the Queen of Heaven.21 This Throne of Wisdom pose was a very popular way to represent the Virgin and Child in the late Middle Ages and can be seen throughout the cathedral. The most famous example of the Throne of Wisdom at Chartres would of course be the lost Romanesque statue seen on most pilgrim’s badges.

Many scholars have attempted to complicate this imagery by pointing out that Mary here is not meant to embody wisdom and power herself, but is simply a throne for Christ’s wisdom.22 With all of this, there is certainly a heavily patriarchal view coloring the figure of Mary in that although she is powerful, her power is always less than that of her son. And so, while imagery of the Virgin at Chartres would certainly help attract female crowds, ultimately her power only extended as far as to lead women to the doctrine of Christ.

Figs. 4a-b. Chartres west facade.

Bibliography

Burns, E. Jane. “Saracen Silk and the Virgin’s ‘Chemise’: Cultural Crossing in Cloth.” Speculum 81, no. 2 (2006): 365–97. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20463715.

Caviness, Madeline. “The Feminist Project: Pressuring the Medieval Object.” FKW/Journal of Gender Studies and Visual Culture, no. 24 (1997): 13-21. https://doi.org/10.57871/fkw241997609.

Lamarre, Mark. “The Symbolic Functions of the Enthroned Virgin in the Cathedral of Chartres.” Academia.edu, 2013. https://www.academia.edu/1139016/The_Symbolic_functions_of_the_Enthroned_Virgin_in_the_Cathedral_of_Chartres.

Le Marchant, Jean. Miracles de Notre-Dame de Chartres. Ottawa: Éditions de l’Université d’Ottawa, 1973.

Randles, Sarah. “Signs of Emotion: Pilgrimage Tokens from the Cathedral of Notre-Dame of Chartres.” In Feeling Things: Objects and Emotions through History, edited by Stephanie Downes, Sally Holloway, and Sarah Randles, 43-57. Oxford: Oxford Academic, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198802648.003.0004.

Rousseau, Katherine. “Pilgrimage, Spatial Interaction, and Memory at Three Marian Sites.” PhD diss., University of Denver, 2016. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1129.

Schenck, Mary Jane. “The Charlemagne Window at Chartres: Visual Chronicle of a Royal Life.” Word & Image 28, no. 2 (2012): 135–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/02666286.2012.660306.

Spitzer, Laura. “The Cult of the Virgin and Gothic Sculpture: Evaluating Opposition in the Chartres West Facade Capital Frieze.” Gesta 33, no. 2 (1994): 132–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/767164.

Wolin, Emma. “Mary of Chartres and Eve of Autun: Conflicting Images of Women in the Middle Ages.” New College of Florida Journal of Pre-Modern Studies, no. 2 (2014): 13-22.

Image Credits

Header image. Northern porch of Chartres Cathedral. Photograph by “Txllxt TxllxT”, April 28, 2011. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chartres_-_Clo%C3%AEtre_Notre-Dame_-_Cath%C3%A9drale_Notre-Dame_de_Chartres_1193-1250_-_North_porch_of_Cath%C3%A9drale_Notre-Dame_de_Chartres_%26_Northern_Spire_10.jpg. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 Deed.

Fig. 1. Plan of Chartres Cathedral, in Hugh Chisholm, ed., Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition (1911). Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:EB1911_Cathedral_-_Fig._5.%E2%80%94Plan_of_Chartres_Cathedral.jpg. Public domain.

Fig. 2. Charlemagne presenting a monk with relics on one panel of the Charlemange window. Photograph by Vladimir Renard, October 18, 2023. Source: Vladimir Renard via Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cath%C3%A9drale_de_Chartres,_Vitrail_de_Charlemagne,_Charlemagne_d%C3%A9pose_les_reliques_%C3%A0_Aix.jpg, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 Deed.

Fig. 3. A common pilgrim’s badge showing the Sainte Chemise being carried in procession. Photograph by Jim Forest, February 1, 2007. Source: Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/jimforest/376577224/in/photostream/. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Deed.

Fig. 4a. Chartres west facade. Photograph by Nina Aldin Thune, November 12, 2005. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chartres.jpg. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 Deed.

Fig. 4b. Modified version of fig. 4a.

The Author

Sarah Culhane is a third year student at Vassar College studying art history and religion, with a passion for medieval art.