Dissecting the Miracles and Architectural Design of the Cathedral of Saint-Lazare, Autun

Introduction

Located in the French city of Autun, the Cathedral of Saint Lazarus of Autun (fig. 1) is an example of intricately designed Romanesque architecture. It receives countless pilgrims on their journeys toward Santiago de Compostela. Venerating Saint Lazarus, the cathedral exhibits religious significance from a variety of elements; it is a substantial force in the “pilgrim economy” of Burgundy.

Miracles and the Tomb of Saint-Lazare

According to the Easton Bible, Lazarus was the brother of Mary and Martha of Bethany who contracted a serious illness that led to his death. In desperation, Mary and Martha sent a plea to Jesus Christ, and subsequently Lazarus was resurrected when Christ visited his tomb in Marseilles.1 Risen from the dead, Saint Lazarus devoted himself to preaching in Provence for the remainder of his life.

Consecrated in 1130 by Pope Innocent II, the Cathedral of Saint-Lazare was built to host the relics of Saint Lazarus from Marseilles.2 Although the actual relic failed to survive the upheavals associated with the French Revolution in the eighteenth century, the Tomb of Saint-Lazare exhibits substantial religious significance for visitors.

Instead taking the form of a sarcophagus, the Tomb of Saint Lazarre was constructed as a miniature marble church—two stories tall—located behind the altar of the cathedral. Figure 2 shows a miniature version of the shrine, constructed in wood, currently in the Rolin Museum. Described by art historian Mariette Verhoeven, the shrine featured Lazarus’s resurrection, with sculptures of Christ, Saint Peter, Saint Andrew, the Virgin Mary, and Mary Magdalene surrounding his relics.3

A series of miracles was also performed after the relics were transported into the church, as Elina Gertsman has outlined. The archdeacon of Reims, Ursus, who was suffering from leprosy, was healed in front of the church; a “possessed deaf-mute” was cured after being in proximity to the Lazarus relics.4 Moreover, a pagan princess was cured of infertility, leading to her and her husband’s subsequent conversion to Christianity.5

The significance of the Cathedral of Saint-Lazare rests upon the theme of resurrection. Medieval pilgrims engaged with this theme by stepping into the shrine and experiencing their own resurrection through a mise-en-scène. The intricacy of the marble figures, exemplified by Christ in figure 3, reinforces the visitors’ immersion when stepping “side by side” with these religious figures. Moreover, this theme was accompanied by stories of the miraculous healing effects induced by the church, which added a practical aspect to the pilgrims’ visits.

The Last Judgment Tympanum

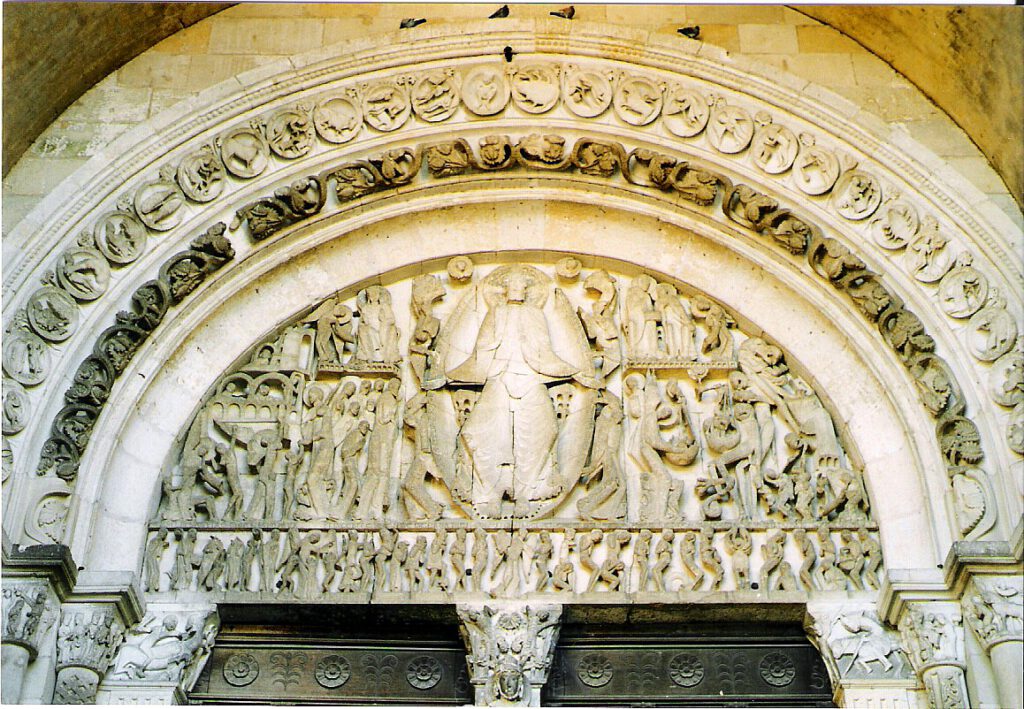

The main portal of the Saint-Lazare depicts the scene of the Last Judgment, which is illustrated in figure 4:

According to art historian Don Denny, the Last Judgment tympanum of Saint-Lazare is a one of a kind:

The tympanum of Autun Cathedral (c. 1130) is in several respects without precedent in western depictions of the Last Judgment.6

Denny reveals how the piece seems disparate from its Byzantium precedents. In Saint-Lazare’s Last Judgment, the artist, who may be identified by the inscribed name Gislebertus at the bottom of the program, has used a novel way to organize the figures, with the Virgin Mary sitting in a frontal position in the top left corner—a depiction unseen in prior Last Judgment sculptures—in the register of heaven (fig. 5).7 Although her role as an intercessor is manifested by situating her at Christ’s right, their relationship is rendered here with ambiguity, as she is affiliated with heaven and clearly separated from the levels below. Moreover, the apostles in this work are not depicted as complementary judges—in coherence with previous works—but rather are more generalized portrayals resembling pious individuals expressing their devotion by looking up to Christ with gestures (fig. 6). These depictions by Gislebertus are likely to have downplayed the authority of their religious affiliations, while Christ’s authority as an “agent of judgment” is heightened by his enlargement and centralization among the clearly delineated scenes of resurrection, judgment, and the entry into heaven.

In contrast with more accurate depictions of the Gospels, Gislebertus was more concerned with the portrayal of human souls in this tympanum, as elucidated by Jamie Wheeler.8 This is clearly manifested in features such as the absence of the lake of fire, a feature of hell mentioned in Revelations. Instead, he invested in the portrayal of the range of torture methods that are inflicted upon the abundant damned to the left of Christ. From the viewers’ perspective, on the right of Christ the archangel Michael weighs the souls while a demon disrupts the process (fig. 7). The damned are subjected to torture: a woman who committed the sin of lust is bitten by snakes and three other figures are tied together by their necks by a demon (fig. 8).

Wheeler suggests that the contrast between heaven and hell should not be seen as opposites—hell is not an isolated domain that contrasts heaven in equal potency, while “Heaven has authority even in Hell, and God’s messenger of just judgment equally dominates the hellish side of image.”9 This is depicted by the incoherence between the depictions of Saint Peter (fig. 9) and the Archangel Michael—while the former guides the worthy in their ascent into heaven, the latter does not dispel souls into hell but rather judges the deeds of the resurrected. This suggests a power dynamic between heaven and hell, as the former still exhibits religious authority and governance over the realm of the damned.

Looking at this novel portrayal of the Last Judgment, a pilgrim was likely to have various religious realizations. The most significant catalyst for such a reaction can be found in the emphasis upon Christ’s omnipotence—extending to a fearful level of authority in the Last Judgment. He is centralized and balances the realms of heaven and hell, extending into the scenes of resurrection, judgment, and ascension. This would have cautioned pilgrims to live an ecclesiastical life, as the damned were subject to a range of tortures. Moreover, among the cascade of mortals waiting to be resurrected are two pilgrims carrying bags marked with pilgrim badges (fig. 10). The cross symbolizes the journey to Jerusalem and the scallop shell to Santiago de Compostela.10 The depiction of these pilgrims allowed real pilgrims to imagine themselves represented in the scene, reinforcing the religious power of the tympanum visitors.

The Lintel of the Temptation of Eve

Drag and zoom to explore the above interactive 3D model. Model by Zoilo Perrino on Sketchfab.

The lintel fragment from the North Portal (ca. 1130) of Saint-Lazare depicts the Temptation of Eve (fig. 11). This lintel fragment, discovered in 1856, is said to be the only surviving part of the North Portal of Saint-Lazare.11 However, a written account composed in 1482 indicates that the North Portal consisted of the Resurrection of Saint Lazarus on the tympanum with stories of Adam and Eve—exemplified by this lintel fragment—depicted below.12 Although the depiction of Adam is lost, there are various features of Eve that are worthy of examination. In this fragment, Eve is depicted with a curled body crawling on the ground, alluding to God’s punishment that she mimic the serpent following her temptation. Her curved body shape, stereoscopic breasts, the vines covering her genitals, and the plucking of the forbidden fruit with her right arm indicate the inherent themes of lust and desire.13

The lintel fragment of the Temptation of Eve is rich in religious motifs. Art historian O. K. Werckmeister has delved into the significance of Eve’s pose. Eve’s right hand gently supports her head and her fingers are outstretched, while her body reclines toward the left, in close proximity with the vine.14 The Bible of San Paolo references such gestures as denotations of grief. Accompanied by the vines used to cover her shame and the forbidden act performed by her left hand, the image of Eve resembles a web of lustful intentions, her inherent shame, and grief after the punishment by God.

Linda Seidel argues that Eve’s character overlaps with that of Saint Mary Magdalene. For Seidel, the particular depiction of Eve at Autun, prostrate and weeping, recalls the behavior of Mary Magdalene at the feast at Bethany following Lazarus’s resurrection.15

Adding to the discussion of the curious depiction of Eve, Marian Bleeke focuses on Eve’s grief, an emotionalism that may have reflected and encouraged that of pilgrims. She carefully explores the details of Eve’s face (fig. 12), noting that her pupils are enlarged, the contours of light giving a sense of moisture and “softness,” which may support Seidel’s argument.16 The assertion that Eve and Saint Mary Magdalene are conflated is made all the more plausible after understanding that Lazarus’s resurrection is only depicted in two locations—in the mise-en-scène within the shrine and on the destroyed tympanum of the North Portal above the lintel—while the sculpture of Saint Mary Magdalene (fig. 13) and Eve’s lintel accompany each of these scenes.

This parallel is reinforced by the common facial features between the depictions. The eyes of the two figures have deep-set eyes with heavy eyelids, reinforcing that the figures were emotionally distressed—Eve for her punishment and Mary Magdalene (often conflated with Mary of Bethany in the Middle Ages) for the grief of her brother, Lazarus.

The fact that Eve and Saint Mary Magdalene and Martha flank the two resurrection scenes of Lazarus—with their common facial features—supports the “conflation” of Eve in the lintel with Saint Mary Magdalene. The placement of the Fall of Man under Lazarus’s resurrection allows the pilgrim not only to visualize the range of secular wrongdoings that were common in medieval life, but also to realize “the importance of their acceptance and admittance of their sins.”17 Moreover, the conflation of Eve and Saint Mary Magdalene was speculated to induce self-reflection in pilgrims—as Eve resembles a common sinner—after being emotionally affected by the resurrection in the shrine, accompanied with sculptures of saints like Mary Magdalene.

Conclusion

It is evident that Saint-Lazare offers a comprehensive view of the theme of resurrection, with each of its elements engaging pilgrims in slightly different ways. The miracles, whether of the holy resurrection of Saint Lazarus or the healing powers of his relics, encouraged the pilgrims to engage with the cathedral and the shrine. The Last Judgment tympanum, however, illustrates the lawful order and authority of Christ in weighing mortal deeds, suggesting the importance of living a faithful and pious life. Lastly, the lintel of Adam and Eve—with the Resurrection of Lazarus as its tympanum—evokes significant emotional turmoil in pilgrims and elicits self-reflection on their own sins. The complexity of novel expressions—exemplified by the “resurrection” of Saint Lazarus—in the Romanesque Christian world calls for a “schematic way” of organizing beliefs and meaning. As Marthiel Mathews claims, “there are many levels of meaning to be found in the work of Gislebertus in the Cathedral of Saint Lazarus by those wise in the Romanesque way of seeing.”18

Bibliography

Cassar, Elizabeth. Foreword to Who Was Saint Lazarus?, 5–6. Malta: Lulu Press Inc., 2017.

Denny, Don. “The Last Judgment Tympanum at Autun: Its Sources and Meaning.” Speculum 57, no. 3 (1982): 532–47. https://doi.org/10.2307/2848692.

Gallagher, Edward J. “The ‘Visio Lazari,’ the Cult, and the Old French Life of Saint Lazarus: An Overview.” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 90, no. 3/4 (1989): 331–39. www.jstor.org/stable/43343942.

Gertsman, Elina, and Marian Bleeke. “The Eve Fragment from Autun and the Emotionalism of Pilgrimage.” In Crying in the Middle Ages: Tears of History, 16–31. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Kraus, Henry. “Eve and Mary: Conflicting Images of Medieval Woman.” Feminism and Art History (2018): 78–99. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429500534–6.

Latin Vulgate Bible with Douay-Rheims and King James Version Side-by-Side Complete Sayings of Jesus Christ.

Mathews, Marthiel. “Gislebertus Hoc Fecit.” Gesta 1/2 (1964): 22–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/766619.

Rockford, Riley J. “Representations of Eve and the Church at Autun.” Religion and the Human Condition Conference. Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2019.

Seidel, Linda. Legends in Limestone: Lazarus, Gislebertus, and the Cathedral of Autun. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Stokstad, Marilyn. “Romanesque Art.” In Medieval Art. London: Routledge, 2019.

Verhoeven, Mariëtte. “Appropriation and Architecture: Mary Magdalene in Vézelay.” In Monuments & Memory Christian Cult Buildings and Constructions of the Past, 107–20. Edited by Lex Bosman, Hanneke van Asperen, and Mariëtte Verhoeven. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2016.

Waller, J. G. “On a Sculptured Capital in the Cathedral of Autun.” Archaeological Journal 27, no. 1 (1870): 255–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/00665983.1870.10851488.

Werckmeister, O. K. “The Lintel Fragment Representing Eve from Saint-Lazare, Autun.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 35 (1972): 1. https://doi.org/10.2307/750920.

Wheeler, Jamie. “Gislebertus d’Autun and the Narrative of Scripture.” Aletheia 3, no. 1 (2018): 3–8. https://doi.org/10.21081/ax0149.

Image Credits

Fig 1. Saint-Lazare. Source: “Autun Cathédrale St. Lazare” by Zairon, taken from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Autun_Cathédrale_St._Lazare_7.jpg, is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Fig. 2. A miniature of the shrine, made in wood. Source: “Tomb of Saint Lazare, Autun” by Anne Heath, taken from https://scalar.usc.edu/works/la-trinit-de-vendme/media/Web%20Tomb%20Lazare.jpg, is licensed under CC BY 3.0.

Fig. 3. Sculpture of Saint Andrew in the shrine. Source: “This World With Devils Filled: Gislebertus at Autun,” © Counterlight’s Peculiars. Taken from http://counterlightsrantsandblather1.blogspot.com/2014/08/this-world-with-devils-filled.html. Owner of blog permits free use of his or her images.

Fig. 4. The Last Judgment Portal. Source: “Autun St Lazare Tympanum” by Lamettrie, taken from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Autun_St_Lazare_Tympanon.jpg, is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Fig. 5. Virgin Mary on the Last Judgment tympanum. Source: “Autun St Lazare Tympanum” by Lamettrie, taken from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Autun_St_Lazare_Tympanon.jpg, is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Fig. 6. Apostles looking up to Christ. Source: “This World With Devils Filled: Gislebertus at Autun.,” © Counterlight’s Peculiars. Taken from http://counterlightsrantsandblather1.blogspot.com/2014/08/this-world-with-devils-filled.html. Owner of blog permits free use of his or her images..

Fig. 7. Archangel Michael weighing souls. Source: “St. Michael weighing souls” by Sarah Cantor, part of the “Images of Medieval Art and Architecture” project © Alison Stones, taken from https://www.medart.pitt.edu/image/France/autun/WestFacade/CentralPortal/Tympanum/Autun-CTymp-014-s.jpg. Permission is granted for reproduction and use of images for non-profit research and educational purposes.

Fig. 8. The damned receiving torture. Source: “Archivolts, Last Judgment Tympanum, St. Lazare, Autun” by Steven Zucker, taken from https://www.flickriver.com/search/Last+Judgment+Tympanum+autun/ licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Fig. 9. Saint Peter on the tympanum. Source: “Archivolts, Last Judgment Tympanum, St. Lazare, Autun” by Steven Zucker, taken from https://www.flickriver.com/search/Last+Judgment+Tympanum+autun/ licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Fig. 10. Portrayal of pilgrims. Source: “Lintel detail: Blessed souls” by Sarah Cantor, part of the “Images of Medieval Art and Architecture” project © Alison Stones, taken from https://www.medart.pitt.edu/image/France/autun/WestFacade/CentralPortal/Tympanum/Autun-CTymp-019-s.jpg. Permission is granted for reproduction and use of images for non-profit research and educational purposes.

Fig. 11. The lintel fragment of the Temptation of Eve. Source: “St. Lazare, Autun: Eve as Temptress, fragment of lintel from portal of north transept, sculpted by Gislebertus” by University of Michigan Library, taken from https://quod.lib.umich.edu/a/aict/x-rq049/RQ049?auth=world;lasttype=boolean;lastview=reslist;resnum=2375;size=50;sort=aict_ti;start=2351;subview=detail;view=entry;rgn1=ic_all;q1=aict. Licensed under CC0 1.0.

Fig. 12. Detail of Eve. Source: “St. Lazare, Autun: Eve as Temptress, fragment of lintel from portal of north transept, sculpted by Gislebertus” by University of Michigan Library, taken from https://quod.lib.umich.edu/a/aict/x-rq049/RQ049?auth=world;lasttype=boolean;lastview=reslist;resnum=2375;size=50;sort=aict_ti;start=2351;subview=detail;view=entry;rgn1=ic_all;q1=aict. Licensed under CC0 1.0.

Fig. 13. Sculpture of Mary Magdalene. Source: “LazareAutun” by anonymous, taken from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:LazareAutun.jpg. Public domain.

The Author

Peter Yik is a fourth-year Psychology student at the University of Hong Kong who endeavours to acquire interdisciplinary knowledge, such as in art history. As manifestations of the psyche, medieval artworks are intricate lenses for probing into human interactions and experience. He will be pursuing further studies in neuroscientific topics to uncover the intricacy of the human mind.