Looking at Irish Pilgrimage from Muiredach’s Cross: Meanings not Set in Stone

Introduction

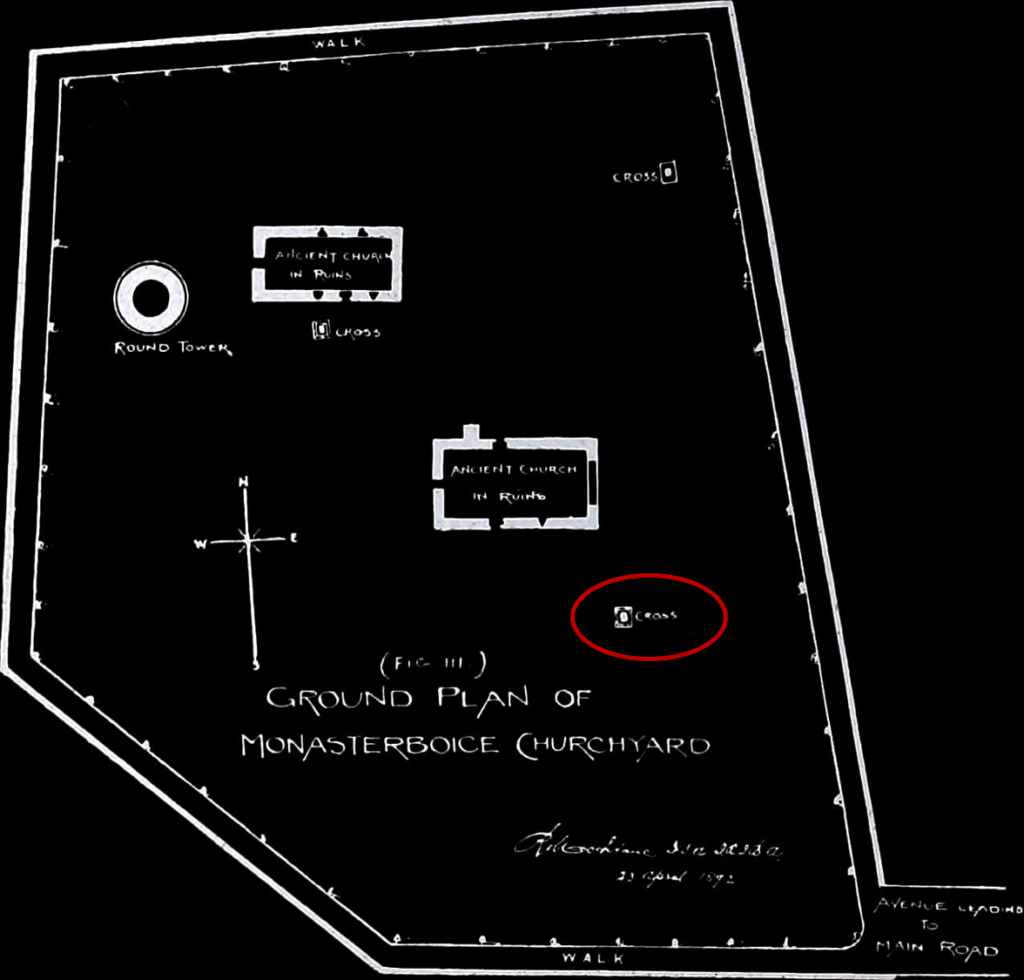

Standing at a height of 5.2m, Muiredach’s Cross (Fig. 1a) is one of the tallest points punctuating this once-monastic settlement of Monasterboice. Approaching from the narrow Southeast entrance of the enclosure (Fig. 2), the cross is the first thing that strikes the eye—a silhouette of solid sandstone against the sky.

A few more steps take viewers in front of the highly decorated surface of the ringed cross, where Christ looms overhead in the Last Judgment (Fig. 1b), at the centre of a Christian narrative programme interspersed with bits and pieces of interlace and other whimsical designs.

Scholars have long considered the possible iconographic “sources” of Irish High Crosses—like Muiredach’s Cross—to be early Christian Roman sarcophagi and Coptic textile.1 How did Ireland that is at “the world’s edge”, in the words of the seventh-century Irish monk Columbanus, possibly connect with Rome and Egypt?2 Dorothy Verkerk is the first to propose pilgrimage as the transmission method.3 The footsteps of Irish pilgrims may indeed be the invisible thread drawing all of these disparate dots on the map together. The physical pilgrimage journey, however, is perhaps only half of the story. The conception—especially the Irish conception—and practices of pilgrimage should also enter the picture if we are to (re)imagine the nebulous meanings that were once captured, maybe, but not set in stone on Muiredach’s Cross in Monasterboice.

3D model of Muiredach’s Cross. Zoom and drag to explore.

Pilgrimage to Rome: There and Back Again?

Pilgrimage to Rome was also popularly known as pilgrimage ad limina apostolorum—“to the threshold of the apostles”—which means that the pilgrim’s chief business would be to visit the “thresholds, or tombs, of Saints Peter and Paul,” among other early Christian saints.4 Arriving at Rome would probably have been, as it is now, synonymous to an onslaught on the senses. Streets inside and outside the city were lined with churches, while catacombs still dotted the land just beyond the city walls. Inside each of these spaces, there were also countless frescos, icons, and sarcophagi for reverent eyes to feast on all day long. One of the images that would certainly have made an impression is the famous Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus (Fig. 3a; detail in Fig. 3b.) in S. Pietro (the old St. Peter’s Basilica). This sarcophagus has been hailed as a possible source for the iconographic design on Muiredach’s Cross (Fig. 4a; detail in Fig. 4b.).5

Fig. 4b (right). Detail of Muiredach’s Cross (West face) – traditio clavium.

As to how the imagery on sarcophagi made it back to Ireland, Verkerk’s explanation is quite convincing: “Being separated from the ties of a tight kinship group, a hallmark of Irish monasticism, the pilgrim is in a marginal state and therefore highly susceptible to visual stimulation and impression.”6 In this way, the images these Irish pilgrims encountered at their destination not only had visual impact while they were there, but would also have become ingrained to their minds, and so become something they took home.

In a letter Cummian, an Irish bishop, wrote to other clergy in Ireland, he recounted the pilgrimage experience his delegates had in Rome. One of the things that may surprise modern readers is the diversity of peoples and cultures these delegate-pilgrims were able to encounter in seventh-century Rome:

And they were in one lodging in the church of St Peter with a Greek, a Hebrew, a Scythian and an Egyptian at the same time at Easter, in which we differed by a whole month. And so they testified to us before the holy relics, saying: As far as we know, this Easter is celebrated throughout the whole world.7

Other than confirming the correct date of Easter, during the time the Irish stayed with these people from different places in Christendom, they could also have learned about their customs, and, as Françoise Henry suggests, even artistic practices and styles.8 When considering the form of the ringed High Crosses, one particular Coptic textile with an image of a jewelled cross (Fig. 5) often enters into the discussion. Made in early Christian Egypt, this textile is generally interpreted to be referencing the actual Crux Gemmata (Gemmed Cross), erected on Golgotha of Jerusalem in the 5th century and contained a piece of the True Cross.9 If there is a grain of truth in this speculation, then it seems that by going to Rome, the delegates (and other Irish pilgrims like them) not only arrived at the threshold of the Roman church, but the crossing of many winding paths that lead to and from different parts of the Christian world.

Cummian’s account of the delegates’ pilgrimage to Rome may also be revealing with regard to the possible intentions and ideas behind the creation of Muiredach’s Cross and other Irish High Crosses. While applying Victor and Edith Turner’s anthropological theory on pilgrimage, Verkerk puts it this way:

Catholic pilgrimage creates communitas, especially through participation in the Eucharist: one leaves his or her regional identity to be subsumed within the larger community of the universal church.10

Having got the confirmation from the delegation that all other Christians indeed celebrated the same Easter—no matter if they were Greeks, Hebrews, Scythians, or Egyptians—Cummian wrote the letter in question to urge his fellow Irish cleric to follow suit. The synthesis of Roman and Coptic stylistic features on the Muiredach’s Cross, then, can be read as a visual representation of this communion with the rest of the Church.

Irish Peregrinatio: “Home is behind, the world ahead—”

Pilgrimage to Rome was not the only way of Irish pilgrimage, nor was the form of the ringed cross the only link the Irish had with Christian Egypt. There is a particular blend of Irish peregrinatio that cares not the destination, only that the pilgrim leaves home behind.11 An early Irish homily actually refers to pilgrimage as “white martyrdom”, in which one turns away from all that is familiar and dear to them “for the sake of God.”12 The way to do it would be to set sail at sea, and let the wind and tide take one where they will. This directionless pilgrimage contrasts sharply with most of the other Christian pilgrimages, where there is a set destination, and so a clear “there and back again” motion. Peregrinatio had been so widespread, especially among monks, that it became an Irish tradition—but it was actually modelled after the ascetic monasticism of the Desert Fathers in early Coptic Christianity.13 This old shared ideology may be why there is a scene of St. Anthony and St. Paul (of Thebes)—the original Desert Fathers—breaking bread on the capstone of Muiredach’s Cross (Fig. 6). Strictly speaking, this is a foreign iconography perhaps, but the same spirit of monasticism had become so deeply ingrained in Ireland for so long that it had ceased to be foreign influence, but rather part and parcel of Irish Christianity.

There were some Irish monks who went on peregrinatio and actually landed somewhere else and became missionaries. The one who went the farthest was probably St. Columbanus and his company, who first landed in Brittany, and then went as far as Switzerland and northern Italy in the seventh century.14 Such acts of evangelism curiously echo the idea behind the traditio clavium on the cross, which is related to the apostles’ mission to become the foundation of the Church and to spread the Word of the New Covenant “to the ends of the earth.”15 The local flavour of Irish peregrinatio seems to have come full circle to reconcile with the vision of the one universal Church once again.

Epilogue: “Not all those who wander are lost”

There is an inscription is at the base of Muiredach’s Cross soliciting prayers for its titular patron—Muiredach, one of the abbots of Monasterboice. Visitors are meant to kneel down in prayers in front of the cross.16 The question is: who would have knelt before the cross? Henry Morris’s intriguing—though still much contested—interpretation puts forward the possibility of there being a mix of Irish and Viking, newly converted, Christians at Monasterboice.17 If that is true, then the Vikings had come by boat—like how the Irish would do if they were going on peregrinatio—and eventually arrived at the holy site of Monasterboice where the relics of its founder St. Buite were housed.18 It would almost be like they had gone on an accidental pilgrimage. This would ring especially true in the spiritual sense—Augustine had called all Christians his “fellow-pilgrims” and “companions of [his] way.”19 These Viking converts, if they were indeed present at Monasterboice, would also be pilgrims on their lifelong journeys in search of God.

No matter if it was Rome at the centre, or Ireland or Egypt at the far end of the earth, pilgrimage has a way of bringing peoples, arts, and ideas together. Just as meanings are not set in stone on Muiredach’s Cross, the constant movements of these different parties are always criss-crossing one another’s paths, never settling down.

Bibliography

Birch, Debra J. Pilgrimage to Rome in the Middle Ages: Continuity and Change. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 1998.

Cummian. De Controversia Paschali. Digitalised by the Corpus of Electronic Texts (CELT), a project of of University College, Cork. Accessed 3 Dec, 2019. https://celt.ucc.ie//published/T201070.html.

DeAngelo, Jeremy. “Imitating Exile in Early Medieval Ireland.” In Outlawry, Liminality, and Sanctity in the Early Medieval North Atlantic. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019, 69-104. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv92vpqj.6.

Dunn, Marilyn. The Emergence of Monasticism: From the Desert Fathers to the Early Middle Ages. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2000.

Harbison, Peter. The Golden Age of Irish Art: The Medieval Achievement 600-1200. New York: Thames and Hudson Inc., 1999.

Henry, Françoise. Irish Art in the Early Christian Period. 2nd edition. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1947.

McHugh, Ned. “Monasterboice Conservation Study: Selected Excerpts.” Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society 27, no. 2 (2010): 177-215. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41433021.

Morris, Henry. “The Muiredach Cross at Monasterboice. A New Interpretation of Three of Its Panels.” The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Seventh Series 4, no. 2 (Dec 1934): 203-12. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25513737.

Roe, Helen M. “The Irish High Cross: Morphology and Iconography.” The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland 95, no.1 (1965): 213-26. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25509591.

Saint Augustine. Book X. The Confessions of Saint Augustine. A.D. 401. Translated by E. B. Pusey. Available on Project Gutenburg. Accessed 4 Dec, 2019. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/3296/3296-h/3296-h.htm#link2H_4_0010.

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. London: HarperCollinsPublishers, 2007.

Verkerk, Dorothy Hoogland. “Pilgrimage ad Limina Apostolorum in Rome: Irish Crosses and Early Christian Sarcophagi.” In From Ireland Coming: Irish Art from the Early Christian to the Late Gothic Period and its European Context. Edited by Colum Hourihane. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001. 9-26.

Werner, Martin. “On the Origin of the Form of the Irish High Cross” Gesta 29, no. 1 (1990): 98-110. https://www.jstor.org/stable/767104.

Image Credits

Header image. “The Cross of Muiredach – IMG_7015.” Photograph by Felipe Garcia, April 2, 2017. Source: Creative Commons, https://ccsearch.creativecommons.org/photos/e647bf0e-8a0b-4d5d-a694-cd33fa09d5dc. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Fig. 1. Muiredach’s Cross (East face). Photograph by kewing, June 8, 2017. Source: Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/32219803@N00/36701556251. Licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Fig. 2. Monasterboice ground plan, in Robert Alexander Stewart MacAlister, Muiredach, Abbot of Monasterboice, 890-923 A.D.: His Life and Surroundings (Dublin: Hodges, Figgis Co. Limited, 1914), p.76. Digitalised by Internet Archive. Source: Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/internetarchivebookimages/14591116489/. Public domain.

Fig. 3a. Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus. Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarcophagus_of_Junius_Bassus#/media/File:Tesoro_di_san_pietro,_sarcofago_di_giunio_basso.JPG. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Fig. 3b. Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, details – traditio legis. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Sarcophagus_of_Junius_Bassus#/media/File:Vatican_Museum_(5986707445).jpg. Cropped image licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Fig. 4. Muiredach’s Cross (West face). Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muiredach%27s_High_Cross#/media/File:Muiredach’s_High_Cross_(west_face)_(photo).jpg. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Fig. 5. Coptic textile with jewelled cross. The Centennial Fund: Aimee Mott Butler Charitable Trust, Mr. and Mrs. John F. Donovan, Estate of Margaret B. Hawks, Eleanor Weld Reid, Minneapolis Institute of Art Accession Number: 83.126. Source: Minneapolis Institute of Art, https://collections.artsmia.org/art/3149/curtain-coptic. Public Domain.

Fig. 6. Detail of Fig. 1. Muiredach’s Cross (East face). Cropped image licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

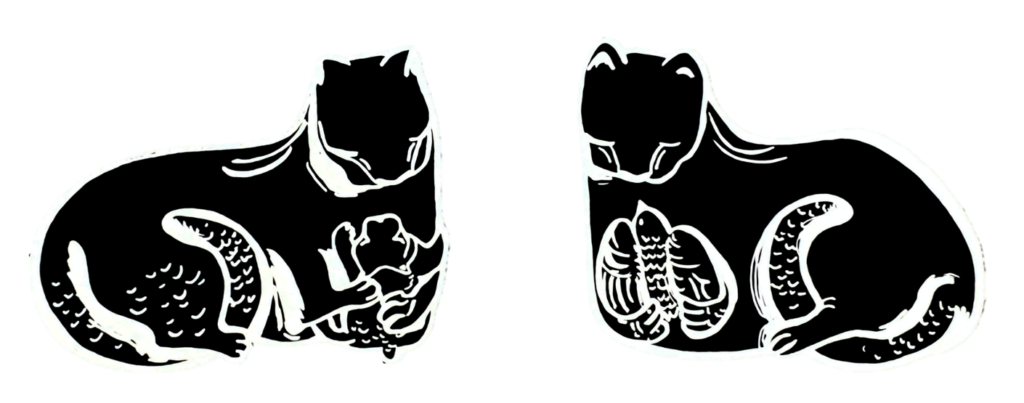

Footer image. Illustration of sculptural details at the foot of Muiredach’s Cross (West face), showing two cats: the left one holding a kitten and the right one holding a bird. © Gigi Leung.

The Author

Gigi Leung received her Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Hong Kong, with a double major in Fine Arts and English Studies. An exchange year at the University of Edinburgh first ignited her interest in medieval art, literature, and culture.