Medieval (Re)interpretation of the Holy Places: Virtual Pilgrimage, Matthew Paris’s Itinerary Map, and Meditative Tools

Introduction

Matthew Paris’s map demonstrates the medieval practice of monks partaking in a virtual journey to the holy Jerusalem. Welsh pilgrimage poetry, architectural replicas of the Holy Sepulchre in Europe, and the map show the wealth of creative approaches taken by devout Christians in the Middle Ages to simulate pilgrimage experiences from different individual perspectives and local social contexts.

Virtual Pilgrimage

In medieval Europe, the pilgrimage journey was not always an option for the faithful who longed to visit spiritually revered sacred sites. It was an extensive investment of time and resources, with unforeseeable fatal risks and dangers along the way that limited socially underprivileged and vulnerable populations, such as children and women, from experiencing first-hand the spiritual reward of pilgrimage.1 At the same time, some social groups, such as cloistered monks, who were confined with strict rules and norms, were also restricted from joining the cohort of pilgrims.2 In such cases when conducting an actual pilgrimage was not an available option, virtual or imagined pilgrimages were a substitute taken by many devout Christians.

A virtual pilgrimage is an imagined spiritual journey to sacred sites along the way to the Holy City conducted in one’s mind, transcending the inevitable constraints of time, space, and resources. It allows one to “[experience] pilgrimage through objects, at a distance from the site of pilgrimage but via items relating to it,” with such items inciting a cognitive association with the pilgrimage or the experience of the pilgrimage as a whole.3

Meditation practices and tools derived from and evolved for these contemplative and highly internal exercises for these journeys to Jerusalem varied across contexts and social groups. The aim of these practices was primarily to activate a multisensory experience of the self in a temporarily imagined sacred site. Eventually, one could achieve transient transport to the far-flung Jerusalem, as a terrestrial sacred city, or even the spiritually heightened Heavenly Jerusalem, the cosmological vision of a city in the account of the apocalypse. The two may often have been superimposed and were therefore “virtually interchangeable” in the minds of medieval viewers.4 Developed as evocative cues, the employment of the medieval meditation techniques can be seen as a negotiation of time and space that can be understood as an epistemological link between a personal interpretation of Jerusalem and the representation of Jerusalem through the intercession of these tools.

Compared to the medieval period, our lives are now full of visual representations of different things. From printed tourists’ guidebooks to travel blogs on social media, contemporary people are familiar with visual representations or records of their travels. Utilizing common digital gadgets, we can even sit back and enjoy a virtual tour in the Holy City of Jerusalem from the couch, freely gazing and wandering around the sacred spaces from different viewpoints.

See above a Virtual Tour of Holy Jerusalem created by the Official YouTube Channel of the State of Israel, April 13, 2020, for pilgrims and visitors who were not able to travel to Jerusalem during Passover and Easter this year because of the pandemic.

Contemporary travelers can even pre-experience a journey before embarking on the actual journey itself and effortlessly construct anticipation for these places through an abundance of visualizations in different forms. The splendor and spectacle of the venerated Holy City are no longer as wholly novel or inaccessible as they had been to most medieval Christians.

Going back several centuries to the era before the birth of digital technology and widespread visual consumption, Matthew Paris’s itinerary map is an example for contemporary viewers to witness the tools and the profound resourcefulness of the minds behind these inventions.

The Pilgrimage Journey on a Map: Matthew Paris’s Itinerary Map

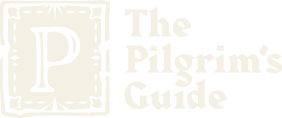

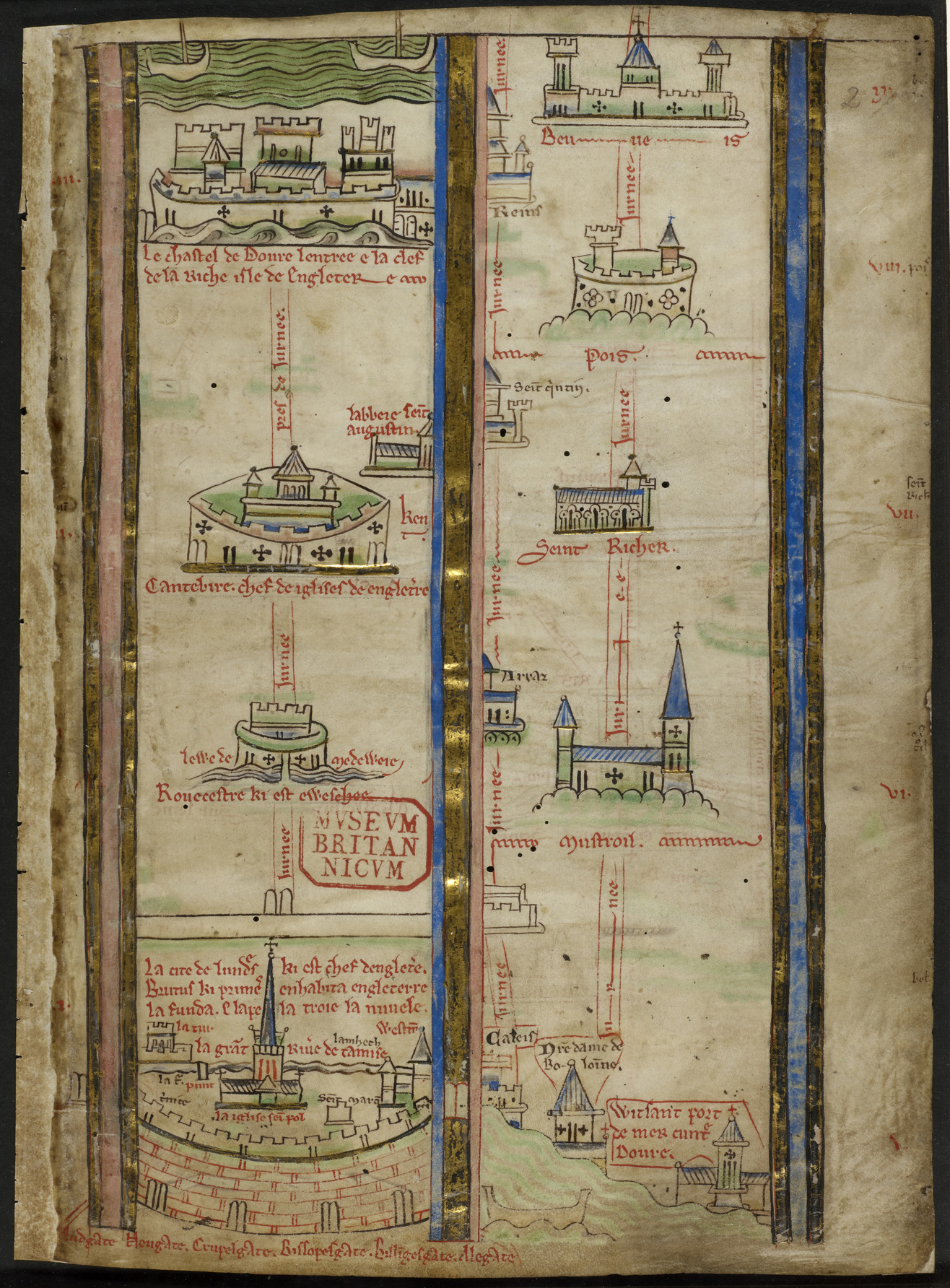

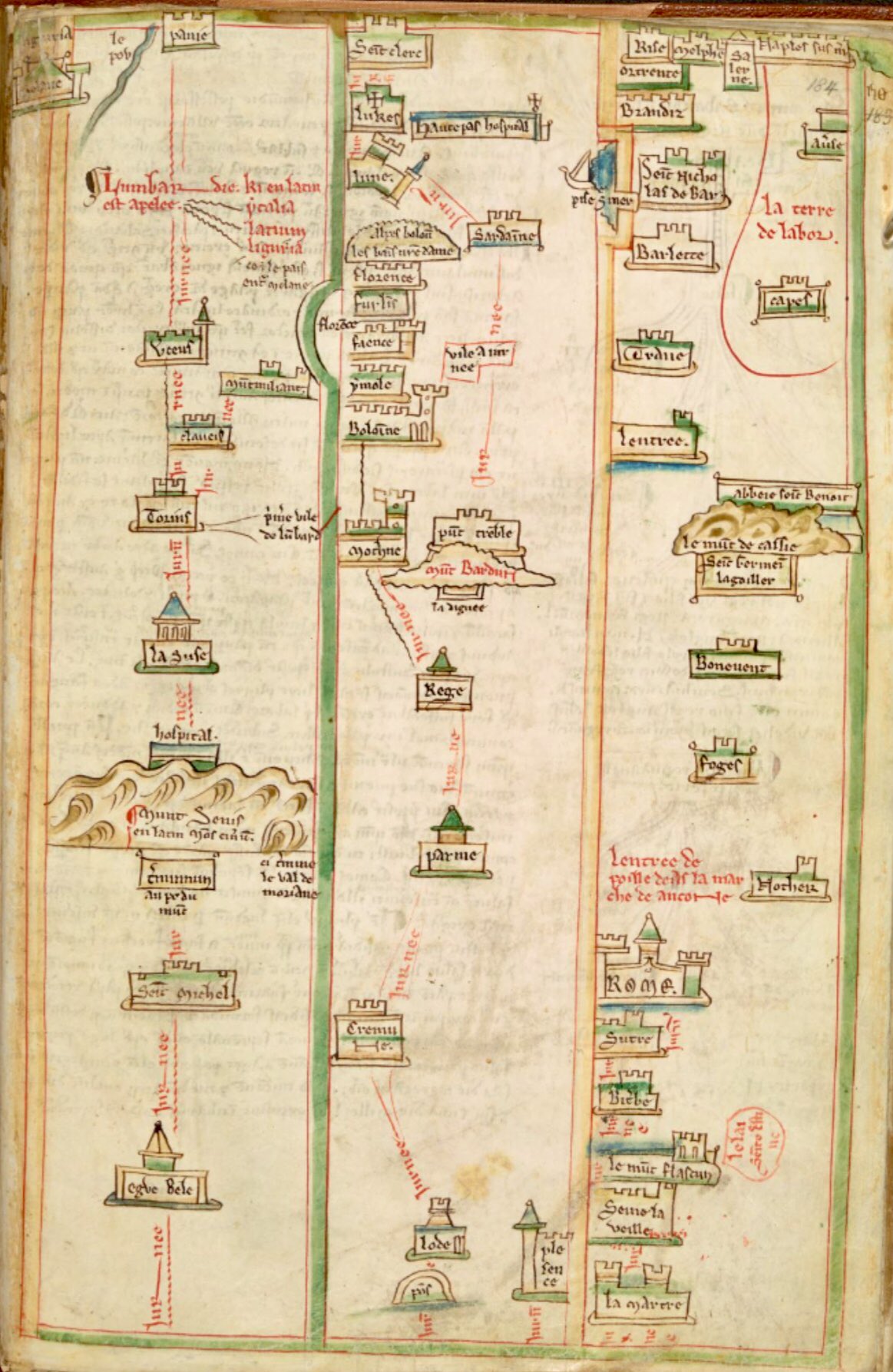

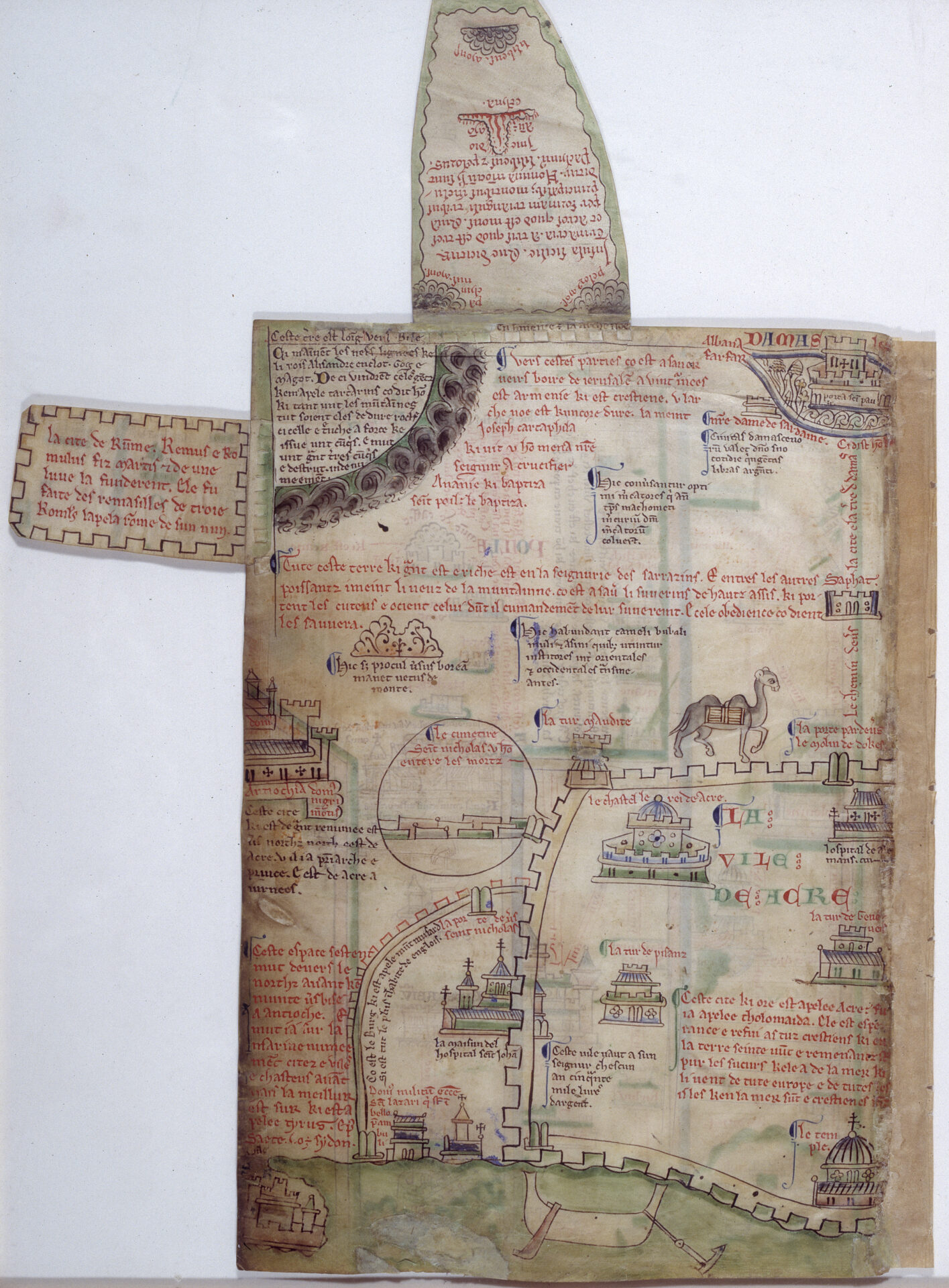

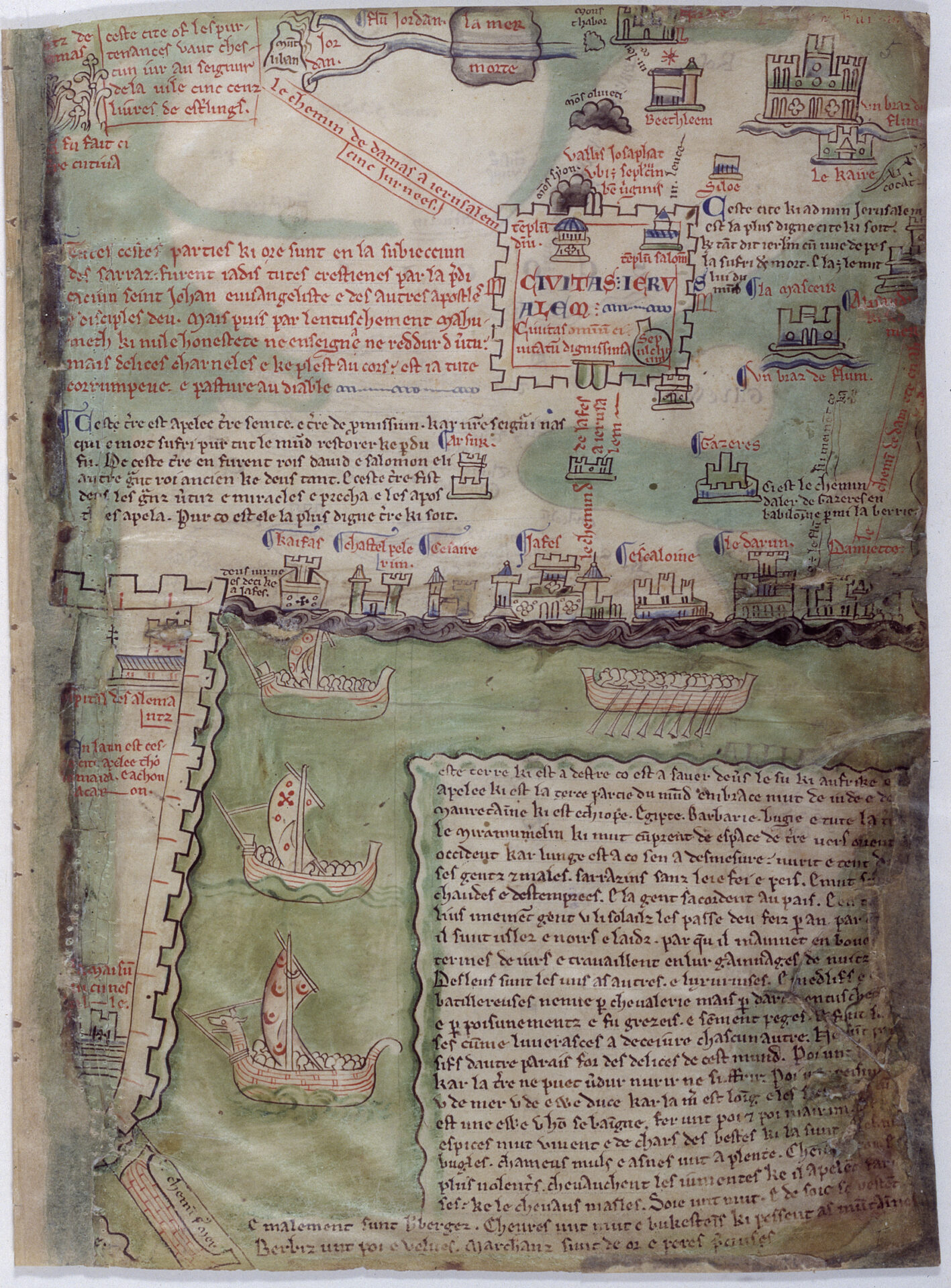

Matthew Paris’s map is a seven-page itinerary map of the Holy City pilgrimage (figs. 1–4), charting the beginning of the journey in London to the destination in Jerusalem. It was written and illustrated by the chronicler and Benedictine monk Matthew Paris at the Abbey of St. Albans in mid-thirteenth-century England. This road map was originally included as part of the prefatory materials of the renowned manuscript Chronica majora, a massive account covering genealogies, astronomy, and history.5 The map was used as a meditative aid for the Benedictine monks, who had taken a vow of stability and lived a cloistered monastic life, to conduct a spiritual pilgrimage to Heavenly Jerusalem, the ultimate spiritual goal of every pilgrimage. Whether the pilgrimage was physical or spiritual, the elevation of the soul was valued and “prized above any actual journey.”6 Serving as a meditative tool for monks to shift their spiritual consciousness to an imaginary journey to the sacred city of God, the visual representation of places and the organization of space is simplified in the map. It facilitates the spiritual heightening of contemplation needed to seek Heavenly Jerusalem, an otherworldly city of God, in the internal space of the monks, not in the actual physical world.

The pilgrimage journey is here compressed and simplified in a rather stylized visual representation. The consistent application of mixed vantage points—mostly aerial views and side views of architectural structures, figures, and natural forms, such as mountains and rivers, that characterize the process of transportation—convey a sense of visual flatness. The sacred places are represented by simple miniature architectural illustrations with geometric and symmetrical elements, rigid lines, and gentle color washes. In the first five pages, the sacred sites are located along the central horizontal axis of each framed column, while in the remaining pages devoted to the Holy Land and Jerusalem (see figs. 3, 4) the distribution of the buildings are less rigid and show more figurative images, like animals and humans. Different routes are shown and arranged in a highly organized and regular way to illustrate the linear sequence of different sites along the whole pilgrimage journey, as well as different possible itineraries for the user to study and contemplate. The chronicler records the travel time needed to proceed to each point and the name of the sacred site, and some of the folios are filled with a profusion of textual accounts in Old French, including descriptions and legends related to the depicted sites.7

Welsh Pilgrimage Poetry

Outside the Benedictine monastery, one of the dominant meditative tools adopted in the non-monastic Welsh community was poetry on the pilgrimage experience.8 These textual accounts are recorded in words that were either transmitted in the form of written accounts or oral performances. Sight and hearing were involved in comprehending the written poetic accounts of pilgrimage and the verbally performed poetry, in turn generating both a virtual experience and an internal vision, as if the virtual pilgrims were having multisensory experiences themselves. As one can imagine, their mental journeys varied due to different bodily gestures, linguistically prosodic features used, and the context of each performance.

Similar to the itinerary map, one fifteenth-century Welsh example is a brief poetic description of the pilgrimage to Rome, which gave signposts to people with a certain amount of geographical knowledge:

I am doing penance / Three roads to Peter and Paul / I walked in search of them / From Anglesey to Rome yonder, / The Rhine Valley and the extensive land of Burgundy, / Italy, Lombardy once again, / Brabant and Germany together, / Swabia, and Flanders as well.9

Compared to the monastic map, this poetic description is more simple and brief, simply illustrating the redemptive nature of pilgrimage and the routes to Rome without any account or discussion of Christian exegesis to directly incite contemplation about doctrine and scripture. The poetry was composed in the vernacular Welsh language, so it was comprehensible to a wider audience. The subject matter of these poems is diverse, ranging from the danger of sea crossing and safe homecoming, which dominated in the fifteenth century, to the spiritual rewards and the sight of sacred places on pilgrimages, seen in the twelfth to fourteenth centuries.10 With these different themes, the poems highlight the practicality and personal experience of actual pilgrimage in a descriptive manner. They construct a collective experience for the virtual pilgrimage community, as it was more relatable and accessible for devout Christians living outside cloistered communities.11

Communal poetic literature production in late medieval Wales was used to transmit the once private and personal experience and knowledge of pilgrims, regardless of their reasons for partaking in a pilgrimage, to the local population. This simulated an empathetic, common experience, and reinforced community identity and bonding with this collective asset formulated through virtual pilgrimage.

Therefore, Welsh pilgrimage poetry is fundamentally different from the monastic itinerary map. The portrayal of pilgrimage is from a more intimate perspective, even if emphasis is put on the spiritual and devotional perspective, because the works were performed and consumed by the patrons, their families, and even community members. The nature of this tool is essentially personal and individualized.12 In contrast, the map puts limited focus on the physical experience of the pilgrimage journey. Familial intimacy and excitement are apparently not features encapsulated in the pictorial portrayal of pilgrimage in Matthew Paris’s map. Instead of being a visually mesmerizing object for entertainment, the itinerary map was fundamentally utilized as a functional tool for study, through internal contemplation and meditation. Hence, any “unnecessary” decorative ornaments, like marginal illuminations commonly found in medieval manuscripts, especially the humorous, secular, and entertaining ones, would have been unfavorable and inappropriate. The simplicity and consistency of the visual style serve the object’s purpose as a as meditative tool, as discussed by Vasilius, and the scarcity of information or decoration may have been a pragmatic decision to enhance the effectiveness of mental contemplation.13 The information included in the representation of pilgrimage is selective in that it structurally caters the use of the tool to the potential user.

It is clear that the functional goal of the tool and the identity or, more specifically, the social background of the audience were important to the composition and the representation of the pilgrimage experience. The meaning attached to Jerusalem and other pilgrimage sites was slightly different between the Benedictine monks and the Welsh common people. Different experiences—built through the use of tools such as (virtual) pilgrimage and the interaction with people from different backgrounds and practices related to this place—could provide them with different meanings for the city of Jerusalem and other sacred sites.

Architectural Replicas of the Holy Sepulchre

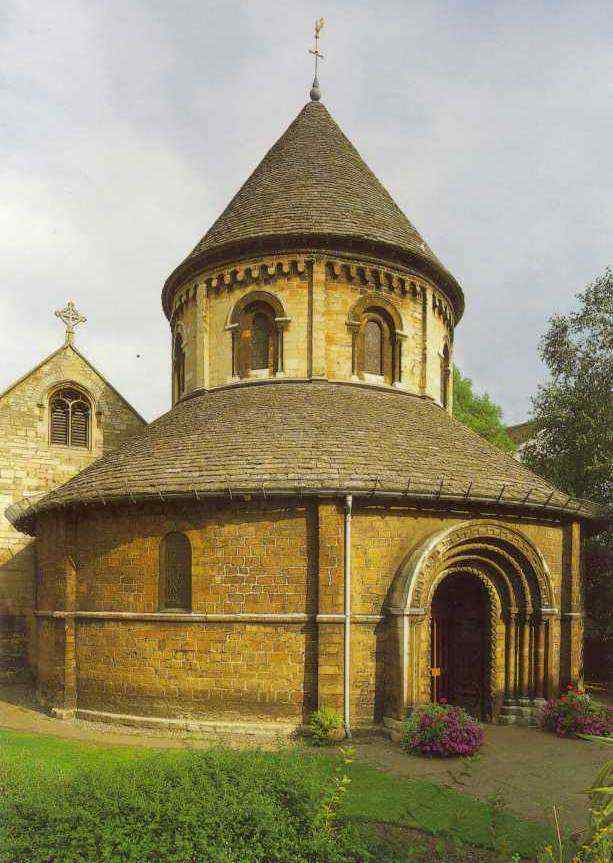

Numerous architectural replicas based on the highly venerated Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem (fig. 5) were erected all over medieval Europe from the fifth to seventeenth centuries for a wide range of intentions.14 The prototype of the Holy Sepulchre was borrowed by and situated in churches, sites of pilgrimage, liturgical dramas, and even cemeteries and baptisteries, with effects ranging from the establishment of civic identity, as in the case of the dedicated copies from Jerusalem at Bologna, to the reflection of the Christian vision of birth and death, as in the case of the baptistery and cemetery in Pisa.15 These edifices also functioned as “sensory simulacra” to replicate the physical spaces, experiences, and sensory engagement one might expect from a pilgrimage journey to Jerusalem.16

Different from a manuscript, these architectural replicas were three-dimensional appropriations of the holy place in Jerusalem in which the physical spaces and corresponding movements were emphasized. A visitor could situate his or her own physical body in the physical construction, one based on the holiest site that medieval Christians longed to visit in person, allowing the performance of devotional activities or theatrical engagement. They served as local pilgrimage sites, an evocative substitute experience, pre-experience, or re-experience of pilgrimage journey to the holy site, where medieval visitors could achieve an “empathic devotional state.”17

Thus, the constant reference to the religiously significant Holy Sepulchre has a different symbolic meaning and function than a manuscript. It signifies the possibility and room for interpretation and reinterpretation of the holy site.18 Regardless of the variety of functions, the sacrality and significance of Jerusalem derived from the multifold interpretation in Christian’s minds are centered in the replica, namely the historical root of Jerusalem as the city of the Jews, the allegorical church of Christ, and the anagogical manifestation of the Heavenly Jerusalem.19

Richard Krautheimer raises an interesting question about the great difference in architectural forms seen among the replicas. Even though the four copies at Fulda, Paderborn, Caen, and Cambridge (fig. 6) he discusses are all direct references to the rotunda of the Holy Sepulchre, three of them are round and one is octagonal, and each has a completely different configuration of the ambulatory, nave, and other architectural features. This shows that there were minimal similarities among the copies.20 More intriguingly, the similarity between the eclectic entombment chapel of the Jerusalem Chapel at Burges and the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem is barely visible to visitors centuries later. Contemporary viewers may be disappointed or perplexed when they find that these “copies” are inaccurate, imprecise, and unfaithful copies of the Holy Sepulchre.

Scholars have provided insight into the medieval notion of architectural copying. Essentially, there is great discrepancy between the contemporary and medieval understandings of exactness and accurateness. To erect a copy in the medieval period, only a few of the outstanding architectural features—often those embedded with religious significance—were selected among a much greater number of features and applied discretely.21 In addition to this selective transfer process, the architectural design could be extended and elaborated on based on the appropriation of other visual elements. The meaning of these amendments was based on the concepts of geometry, numerology, dedications, and their symbolic meanings in medieval Christendom.22 The number of supports and the round shape and the floor plan of the church were all deft employments of Christian semiotics and symbolism.

In other words, the architectural replica was not meant to accurately reproduce the original in terms of measurements, forms, and materials, as one might expect from the analytical scientific approach generally taken in contemporary times. Rather, the symbolic meaning of the holy site and the commemorative character of the copy serve as the core link between the copy and the original.23 As Krautheimer states, “both immaterial and visual elements are intended to be an echo of the original capable of reminding the faithful of the venerated site, of evoking his devotion and of giving him a share at least in the reflections of the blessings which he would have enjoyed if he had been able to visit the Holy Site in reality.”24

Into the Minds of the Benedictine Monks

In the light of the medieval indifference toward visual exactness, we can better understand Paris’s Benedictine itinerary map. The map is far from accurate in a scientific perspective but rather is more likely another type of “sensory simulacra.” Instead of replicating the visual form of the architecture, the simplified symbols of architecture on the map activate the internal knowledge of its monastic users. The vagueness of the cartographic information allows divergent interpretations, for each user can formulate their own individualized journey in their own imagination. In this way, the architectural illustrations with names attached could work in a similar way to the architectural replicas: the visual forms are armatures that carry the symbolic significance of the sites—the notion of sacrality rested in their earthly existence. The handwritten name of the site is an effective stimulus for the monastic viewer to recall the dedication and the source of sacredness, the relics at the holy sites, and the corresponding teaching of the saints.

The cartographic articulation of the map is formulated under a system of syntactic rules that determine the user’s bodily engagement and perception of space. The map is designed to be “read” from the bottom to the top and then from left to right, following the one-way linear order of the route to Jerusalem, consistently vertically upwards and horizontally rightwards to the parallel column. This fixed and patterned bodily movement of the user, in the direction of their gaze and page-turning direction, cultivated a habitual behavior that could be used to decode the iconographic arrangement and extract the information embedded in the simplified visual cues.

This implicates the monastic understanding and identification of the sacred places, manifested in the two-dimensional flat surface with its distinctive visual characteristics. The consistent system of rules in using the material can be also seen as a microscopic exemplar of the structural rule, as the map allows interactive and performative engagement and creative interpretation by the viewers, but these activities are bounded by the syntactic rules of the visual program. To be exact, the great depth of encoded meanings can be decoded legitimately through this system of rules, cultivated through repetitive practices of manipulation and utilization of the map and the knowledge within the monastic mind. Different meanings and interpretations are available through the kinetic engagement of the user, who, configuring and reconfiguring the map, explores the visual composition and relates it to his existing bank of knowledge. As such, the monastic education commonly possessed by the monks possibly enables a more similar interpretation among the group. This process can be conducted far more often than a physical pilgrimage, and the room framed by the physicality of the material tool and the invisible syntactic rules give the basic framework of the cognitive process, while the personal experience, sociocultural background, and knowledge accumulated since birth set the possible variations in interpretation of the meditative tool.

In a broader sense, within the culture of the monastic community, the wealth of theological knowledge and collective concern to achieve a spiritually ideal state enabled this cloistered community to utilize this tool in a specific way. The Benedictine monks were able to activate their theological association with the depicted sacred sites and manipulate their own bodies so as to process the information crystalized in the compressed map. Ideally, this practice would eventually allow them to gain access to the spiritually superior Heavenly Jerusalem through this mentally constructed pilgrimage journey.

Conclusion: A Pilgrimage Journey for All Christians

These medieval meditative tools are far more than byproducts of pilgrimage activities or descriptions of pilgrimage routes. They are profound visual representations of pilgrimage experiences and holy places. Matthew Paris’s map is composed of the interpretation of holy places and the understanding of sacredness and the spiritual significance of earthly existence.

In sum, the invention of meditative tools of virtual pilgrimage is inevitably associated with an extensive system of theological knowledge, the history and interpretation of places, cultural values, and concerns of social groups; as well as their unique practices and bodily engagement with those tools. These intriguing dynamics, complexity, and fluidity also exist in the mind of individuals, where the virtual pilgrimage takes place, as a product of complex social and mental connections.

With the abundance of tools and media for the devout during the Middle Ages, one could travel along the arid pathway to the holy sites, witness an immense storm surge, and kneel before the Tomb of Christ in Jerusalem with the most faithful heart in a virtual pilgrimage. The presence and love of God could be felt by devotees when they immersed themselves wholeheartedly in the internal realm, where time and space were no longer constraints stopping them from visiting the holiest pilgrimage site and also the spiritually sublime Heavenly Jerusalem.

Bibliography

Boulton, Meg. “Introduction: Place and Space.” In Place and Space in the Medieval World, edited by Meg Boulton, Jane Hawkes, and Heidi Stoner, xv-xxi. New York: Routledge, 2018.

Breen, Katharine. “Returning Home from Jerusalem: Matthew Paris’s First Map of Britain in Its Manuscript Context.” Representations, no. 89 (2005): 59–93.

Connolly, Daniel K. “Imagined Pilgrimage in the Itinerary Maps of Matthew Paris.” The Art Bulletin 81, no. 4 (1999): 598–622.

Gelfand, Laura D. D. “Sense and Simulacra: Manipulation of the Senses in Medieval ‘Copies’ of Jerusalem.” Postmedieval 3, no. 4 (2012): 407–22.

Hurlock, Kathryn. Medieval Welsh Pilgrimage, c. 1100–1500. The New Middle Ages. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, 2018.

Krautheimer, Richard. “Introduction to an ‘Iconography of Mediaeval Architecture.’” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 5 (1942): 1–33.

Ousterhout, Robert. “‘Sweetly Refreshed in Imagination’: Remembering Jerusalem in Words and Images.” Gesta-International Center Of Medieval Art 48, no. 2 (2009): 153–68.

Vasiliu, Dana. “A Thirteenth Century Meditational Tool: Matthew Paris’s Itinerary Maps.” B. A. S. British and American Studies, no. 15 (2009): 167–78.

Image Credits

Cover image. Attributed to Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora, Self Portrait of Matthew Paris, England, ca. 1250, British Library, London, MS Royal 14 C VII, fol. 6r. Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matthew_Paris#/media/File:BritLibRoyal14CVIIFol006rMattParisSelfPort.jpg. In the Public Domain.

Fig. 1. Attributed to Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora, Itinerary from London to Beauvais. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Itinerary_by_Matthew_Paris_-_Historia_Anglorum_(1250-1259),_f.2_-_BL_Royal_MS_14_C_VII.jpg, licensed under (CC0 1.0)

Fig. 2. Attributed to Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora, Itinerary from London to Apulia. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tabula_itineraria_ab_urbe_Londinum_ad_Neapolin_et_extremitatem_Apuliae_(Cotton_MS_Nero_D.I,_f.184r).jpeg. In the Public Domain.

Fig. 3. Attributed to Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora, the Holy Land, left half, England, ca. 1250. London: British Library MS Royal 14.C.VII, fol. 4v. Source: British Library, https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/matthew-paris-itinerary-map. In the public domain.

Fig. 4. Attributed to Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora, the Holy Land, right half, England, ca. 1250. London: British Library MS Royal 14.C.VII, fol. 5r. Source: British Library, https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/matthew-paris-itinerary-map. In the public domain.

Fig. 5. Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jerusalem_Holy_Sepulchre_BW_23.JPG, licensed under (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Fig. 6. West front of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Cambridge. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Holy_Sepulchre_Cambridge_Photo.jpg, licensed under (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Illustration. A monk engaging with Matthew Paris’s Itinerary Map, by Jasmin Lin.

The Author

Jasmin Lin: Lifelong artist, art-lover and student of art history and sociology from Hong Kong.