The Furta Sacra in the Church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine

Introduction

The town of Vézelay is a departure point for the major medieval pilgrimage to the tomb of St. James in Santiago de Compostela, Spain, as well as a pilgrimage destination in its own right, as the possessor of the relics of Mary Magdalene.1

Pilgrims visit the Church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine in Vézelay (Fig. 1) to venerate these relics and receive spiritual blessings from the saint. However, the relics of the church are known to have been acquired by furta sacra, or holy theft, the practice of acquiring religious objects like relics of saints through thievery.2 More quizzically, the legends of the furta sacra of the relics of Mary Magdalene are known to have changed over time, and the reasons for this change are in dispute. Regardless, the cult of Mary Magdalene at Vézelay became phenomenally popular with pilgrims in the eleventh and throughout the twelfth centuries.3 The legends and relics of the saint, as well as the architectural and sculptural designs at the Church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine, all served to draw flocks of pilgrims to Vézelay and to usher them off on their journeys to Santiago de Compostela with their faith renewed.

Who is Saint Mary Magdalene?

Mary Magdalene was one of the female disciples of Christ. She is a figure with a great sanctity for having had contact with Christ during his lifetime. Nonetheless, little is known of her actual identity, except that she was a follower of Christ. In the Gospel of Matthew, we learn that

there were there many women afar off, who had followed Jesus from Galilee, ministering unto him: among whom was Mary Magdalene

Matthew 27:55–564

The Gospel of Luke corroborates with: “Certain women who had been healed of evil spirits and infirmities: Mary who is called Magdalen, out of whom seven devils were gone forth, … ministered unto [Jesus] of their substance” (Luke 8:2–3). The Bible also mentions that she was present at the scene of the crucifixion—one of the most significant biblical events—”now there stood by the cross of Jesus, his mother and his mother’s sister, Mary of Cleophas, and Mary Magdalene” (John 19:25). Afterward, Mary Magdalene saw the burial of Christ, as the Bible states, “Mary Magdalen and Mary the mother of Joseph, beheld where he was laid” (Mark 15:47). Mary Magdalene also witnessed the resurrection of Christ, another important event in the life of Christ. The Bible states that she beheld “the stone taken away from the sepulcher” and told the disciples that someone “[has] taken away the Lord out of the sepulcher” (John 20:1–2). Afterward, she “turned herself back and saw Jesus standing” (John 20:14). Because of her presence at Christ’s crucifixion, one of the most significant biblical events, and because Mary Magdalene had frequent contact with Christ and was in close proximity to him in life, she has great spiritual power as a saint.

Mary Magdalene’s unrecorded life, curiously, did not detract from her appeal to medieval Christians. On the contrary, it proved to be the perfect blank slate for the people and the Church alike to spin myths and legends around her, which only served to sensationalize her all the more. The characterization of her as a penitent sinner, for example, stemmed from a conflation of Mary Magdalene with an unnamed woman in the New Testament.5 This persona became so popular that it even made its way into The Pilgrim’s Guide to Santiago de Compostela:

For she is that glorious Mary, who, in the house of Simon the Leper, moistened with her tears the feet of the Saviour, wiped them with her hair, and anointed them with her precious ointment while kissing them assiduously, on account of which her many sins were forgiven her…6

It is not difficult to see why Mary, the penitent sinner, became popular among pilgrims and, in particular, those who travelled to venerate her relics and ask for the remission of their sins—from the saint whose sins had been forgiven by Christ. Who Mary Magdalene was to the medieval French people involves another legend, conveniently recounted in The Pilgrim’s Guide directly following the description of her as a repentant sinner. According to this account, she “arrived by sea from the region of Jerusalem with the blessed Maximinus, disciple of Christ, and other disciples of the Lord, in the land of Provence, that is, through the port of Marseille.”7 While there, she “led a celibate life for several years, and finally was buried in the city of Aix.”8 This story, which attempts to explain how Mary Magdalene’s remains ended up in southern France, is, in fact, told alongside a simplified version of the furta sacra legend.

Changes to the Legends of Furta Sacra

According to earlier legends in the eleventh century, Mary Magdalene’s relics had either “simply appeared miraculously in the crypt tomb” at Vézelay or had been brought back by an eighth- or ninth-century monk returning from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.9 In this version, the Vézelay monastery possessed the relics of Mary Magdalene before the reign of Geoffrey (1037–50).10 However, oddly, the presence of the relics was first documented in 1050.11 This was the moment when Mary Magdalene started to gain a reputation as a penitent sinner and became, along with important and renowned saints including the Virgin Mary, Christ, Peter, and Paul, patron of the monastery.12 Reflecting the trend among monasteries and the popularity of the saints, the legend of the holy theft of Mary Magdalene evolved during the eleventh and early twelfth centuries to glorify Vézelay’s newly adopted cult and to legitimize the purported relics as “really” belonging to this patroness.13 Monasteries at that time tried to attract visitors to the church by adding to the value of the relics through the embellishment of legends into furta sacra.

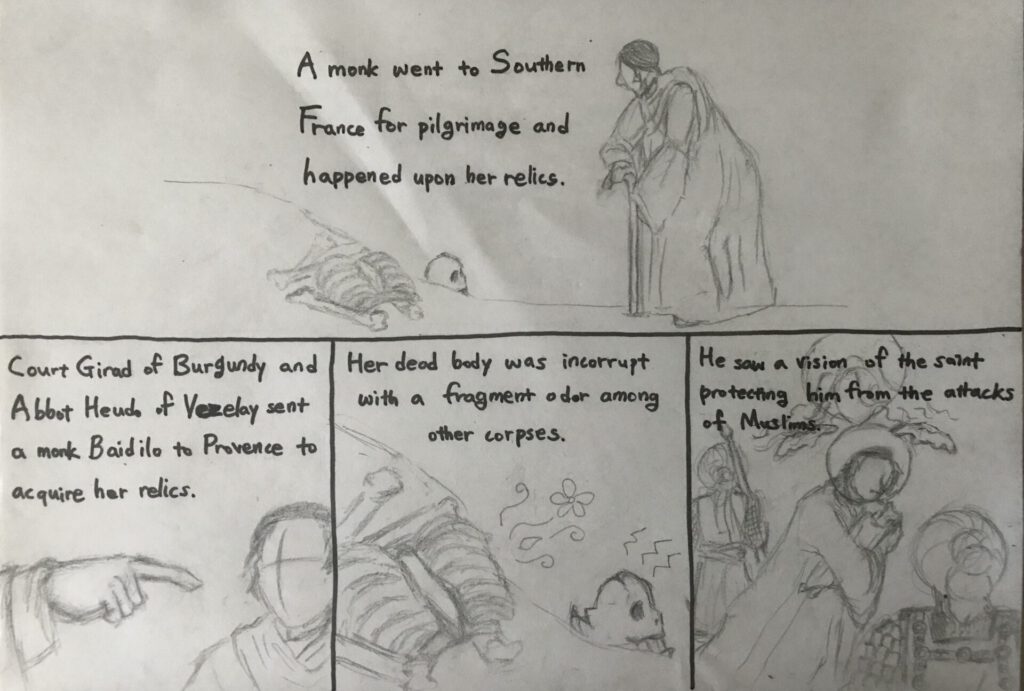

According to a new legend that was “elaborated and perfected during the course of the twelfth century,” Count Girard of Burgundy and Abbot Heudo of Vézelay sent a monk named Baidilo on a mission to Provence to acquire the relics (see Fig. 2 for an illustration of the legend).14 Baidilo was commissioned to carry out the furta sacra because Provence had been overrun by the Saracens.15 In describing Aix-en-Provence as a city full of death and destruction, the monks justified the holy theft as a reasonable action. The legend also describes the monk finding Mary Magdalene’s relics “incorrupt and giving off a fragrant odor.”16 The perfect condition of the relics would certainly highlight the sanctity and power of the saint to the medieval believers. Furthermore, while he was bringing the relics back to Vézelay, the monk saw a vision of the saint, which assured him that his act of furta sacra had her full approval.17 People in the Middle Ages believed that the saints watched over their relics and accompanied the possessor on their journey, offering protection if he or she had acquired them legitimately.18 Therefore, the monk’s vision implies that Mary Magdalene approved of the holy theft, and that she desired to move to Vézelay. Thus, the monk created a signal of approval of his acquisition of the relics, and in so doing he manipulated the public to believe that he had spiritual power that enabled the holy theft.

Reasons for the Holy Theft

Despite the rationalization of the holy theft by relating this action with spiritual significance, monetary value may have also motivated the church to acquire the relics. Because the main purpose of pilgrimage is the veneration of relics, and because Vézelay was the location of the relics of a saint with great spiritual power, the city became an important pilgrimage site.19 At such sites, visitors pray to the saint and donate their money to the church, contributing to its monetary development. The donated money further allowed the abbey to have profitable landholdings in the local area, and the pilgrimage trade helped not only the economy of the monastery but also the economy of the surrounding town.20 Therefore, because the Church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine promoted their acquisition of the relics of Mary Magdalene, the church transformed into one of the leading pilgrimage sites of Western Europe in the twelfth century, resulting in its own monetary prosperity.21 The fact that Vézelay and its furta sacra legend made their way into The Pilgrim’s Guide, as cited above, is a testament to the success of this rationalizing and advertising tactic—the relics and the accompanying legend did attract pilgrims, and with them their offerings, to Vézelay.

Art and Relics at the Church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine

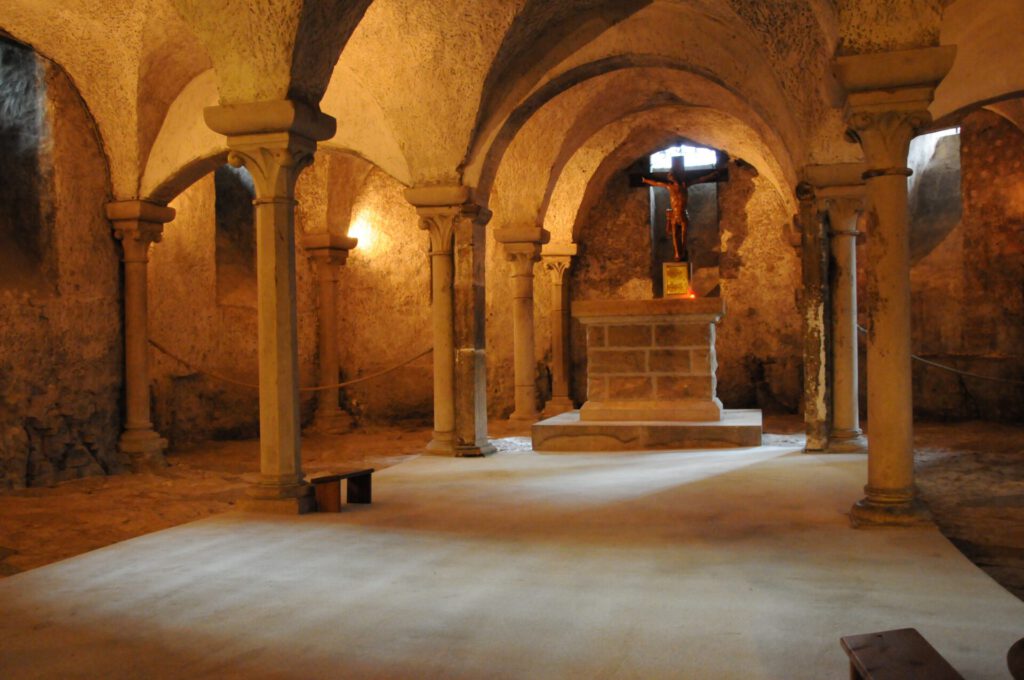

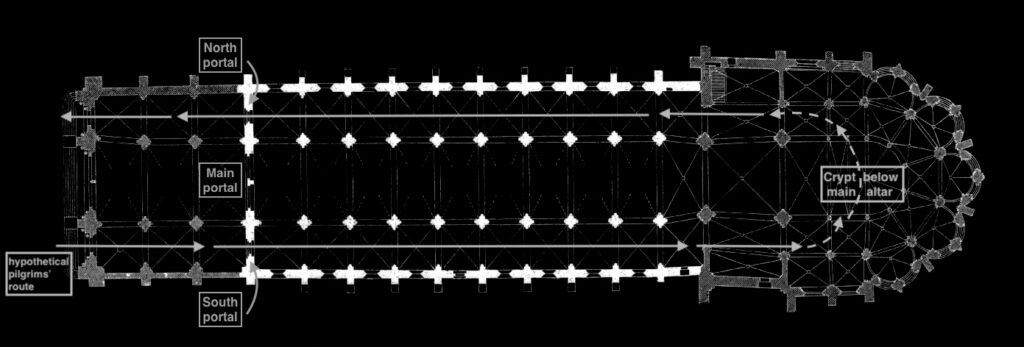

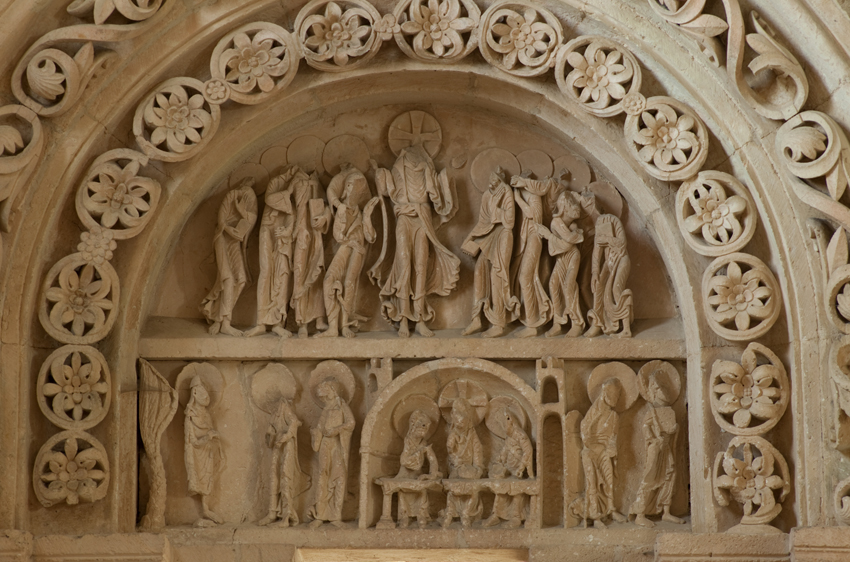

Several sculptural features at Sainte-Marie-Madeleine portray scenes that add to the medieval pilgrim’s experience of coming to see the saint’s relics. The relics of Mary Magdalene were kept in the tomb beneath the main altar in the crypt of the basilica (Fig. 3).22 The easiest way to reach the crypt, which was accessible through staircases to the east of the transept, was to go into the church by either of the side portals (Fig. 4).23 On the tympanum (upper tier) of the south portal is a depiction of the Adoration of the Magi (Fig. 5). As Peter Low points out, not only were the three magi considered the archetypal divinely protected and gift-bearing pilgrims, but the scene of the Adoration also evokes the theme of arrival.24 The north tympanum (upper tier), on the other hand, depicts the Blessing at Bethany (Fig. 6) (Luke 24:50–52), in which the apostles departed for Jerusalem—one of the greatest pilgrimage sites in Christianity.25 This scene would have read as a parallel to the experience of the pilgrims themselves, who would have sought to receive benedictions from the local monks before they set off on their journeys to Santiago de Compostela. The architectural design of the church and the sculptural program on the two side portals, in addition to serving a didactic purpose, potentially create a route for pilgrims visiting the church to venerate the relics of Mary Magdalene.26

The pilgrims arrived at the basilica’s door to venerate the relics, often in the hope of witnessing or experiencing a miracle. Targeting this desire of pilgrims, the sculptures in the main, central portal (Fig. 7a) of the church depict scenes of ailments and healings that could easily be associated with the saint’s miracles.27 The Pilgrim’s Guide to Santiago de Compostela glorifies the spiritual power of Mary Magdalene while urging readers to visit her relics at Vézelay on their way to Compostela, describing her miracles as follows:

There, for love of this saint [Mary Magdalene], transgressions of sinners are forgiven by the Lord, sight is restored to the blind, the tongue of the mute is loosed, paralytics are raised, the possessed are delivered and ineffable benefits are granted to many.28

In the archivolt compartments, there are several groups of figures, including dog-headed people to represent muteness, gesturing figures to show deafness, a man being led to characterize blindness, and people with disabled or painful limbs (Fig. 7b-d).29 Many of the pilgrims who visited and prayed in the Church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine might have felt empowered by these tangible representations of these suffering figures—just like themselves—and also convinced by the saint’s spiritual power in delivering them from sicknesses or injuries.

The sculptural program in the tympana on all three portals of the church, according to Low, work together to illustrate the theme of the transformation of non-apostles into apostles.30 As pilgrims passed from the south to the north portal, it is as if they had passed from being like the magi—non-apostolic travelers and venerators—to being like the apostles at Bethany, who had just seen the face of the holy saint and were about to embark on a journey to a holy site. This theme of transformation also accords with the scene of the Pentecost on the tympanum of the main portal: the apostles are portrayed receiving the Holy Spirit and would soon be ready for their evangelizing mission.31 Now we may recall the persona of Mary Magdalene as the penitent sinner: just as the saint had transformed into a disciple of Christ after meeting him, pilgrims were likely to reflect on the biblical story of Mary Magdalene as they witnessed this imagery in the sculptures. In doing so, the sculptures would have reinforced the reflection of pilgrims on Christian values by illustrating how the stories related, thematically, to Mary Magdalene. In this way, the church subtly stressed its possession of her relics, despite the absence of her imagery in the three portals.32 The overall sculptural program on the triple portals would have encouraged the pilgrims to venerate the relics of the saint and to participate in liturgical ceremonies, so as to be authentic disciples of Christ, just like Mary Magdalene.33 The message of transformation would then be firmly in the pilgrims’ minds as they left Vézelay to commence their pilgrimage along the Camino de Santiago.

Bibliography

Andrea, Alfred J., and Paul I. Rachlin. “Holy War, Holy Relics, Holy Theft: The Anonymous of Soissons’s ‘De Terra Iherosolimitana’: An Analysis, Edition, and Translation.” Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques 18, no. 1 (1992): 152.

Ehrman, Bart D. Peter, Paul, and Mary Magdalene: The Followers of Jesus in History and Legend. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Ferrari-Barassi, Elena. “The Narrative about Saint Mary Magdalene in the Church of Cusiano, Italy.” Music in Art 32, no. 1/2 (2007): 102–12.

Geary, Patrick J. Furta Sacra: Thefts of Relics in the Central Middle Ages. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Latin Vulgate Bible with Douay-Rheims and King James Version Side-by-Side Complete Sayings of Jesus Christ. Accessed April 17, 2020. http://www.latinvulgate.com/logreg.aspx.

Low, Peter David. Envisioning Faith and Structuring Lay Experience: The Narthex Portal Sculptures of Sainte-Madeleine De Vezelay (France). 2001.

Manseau, Peter. “‘Throw Me the Idol, I’ll Throw You the Whip’: Sacred Stories, Holy

Theft, and the Task of the Religion Writer.” CrossCurrents 65, no. 2 (2015): 218–28.

Scott, John and Ward, John O., eds. and trans. Introduction to Hugh of Poitiers, The Vézelay Chronicle and Other Documents from MS. Auxerre 227 and Elsewhere. Binghamtom, NY: Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 1992.

Shaver-Crandell, Annie and Gerson, Paula, eds. The Pilgrim’s Guide to Santiago de Compostela: A Gazetteer. London: Harvey Miller Publishers, 1995.

Image Credits

Fig. 1. The Church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine in Vezelay, France, c. early 12th century Photograph by User:Breeze, September 29 2005. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Basilique_%C3%A0_V%C3%A9zelay.jpg. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5.

Fig. 2. Illustration on the change in legend of furta sacra of the relics of Mary Magdalene, created by Minha Park.

Fig. 3. The Crypt of the Tomb of Mary Magdalene, the Church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine. Photograph by Dorothea Witter-Rieder, May 19 2008. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?sort=relevance&search=crypt+of+vezelay&title=Special:Search&profile=advanced&fulltext=1&advancedSearch-current=%7B%7D&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Vezelay-krypta-dwr-1.jpg. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Fig. 4. Architectural plan of the Church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine, showing hypothetical pilgrims’ route proposed by Peter Low. Originally from G. Dehio and G. von Bezold, Die kirchliche Baukunst des Abendlandes, Stuttgart, 1887-1902, fig. 145, lithograph. Digitalized by Wetman, August 23 2005. Source: Wikipedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Plans_of_V%C3%A9zelay#/media/File:VezelayDB145.jpg. Modified image in the public domain.

Fig. 5. The Adoration of the Magi in the Central Tympanum, the Church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine, Vézelay, c.1120s-1130s. Source: “Tympanum of south portal in narthex” created by G. David Donahue, July 1997, part of the “Images of Medieval Art and Architecture” project © Alison Stones, taken from https://www.medart.pitt.edu/image/france/france-t-to-z/vezelay/portals-sculpture/South-Portal/vezport038s.jpg. Permission is granted for reproduction and use of images for non-profit research and educational purposes.

Fig. 6. The Blessing at Bethany in the North Tympanum, the Church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine, Vézelay, c.1120s-1130s. Photograph by PMRMaeyaert, April 13 2010. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Basilique_Sainte-Marie-Madeleine_de_V%C3%A9zelay_PM_46658.jpg#/media/File:Basilique_Sainte-Marie-Madeleine_de_V%C3%A9zelay_PM_46658.jpg. Licensed by CC BY-SA 3.0.

Fig. 7a. Central portal of the Church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine, Vézelay, c.1120s-1130s. Photograph taken by Vassil, July 15 2008. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/V%C3%A9zelay_Abbey#/media/File:Basilique_de_V%C3%A9zelay_Narthex_Tympan_central_220608.jpg. Public domain.

Fig. 7b. Top compartment on the left of the central portal, showing dog-headed people representing muteness, and neighboring figure groups representing deafness and blindness. Source: “Peoples on Tympanum of Central Portal in Narthex” created by G. David Donahue, July 1997, part of the “Images of Medieval Art and Architecture” project © Alison Stones, taken from https://www.medart.pitt.edu/image/france/france-t-to-z/vezelay/portals-sculpture/Central-portal/Peoples/vezport005b.jpg. Permission is granted for reproduction and use of images for non-profit research and educational purposes.

Fig. 7c. Second-to-top compartment on the left of the central portal, with the left-most figure representing demonic possession, and other figures showing physical ailments. Source: “Peoples on Tympanum of Central Portal in Narthex” created by G. David Donahue, July 1997, part of the “Images of Medieval Art and Architecture” project © Alison Stones, taken from https://www.medart.pitt.edu/image/france/france-t-to-z/vezelay/portals-sculpture/Central-portal/Peoples/vezport004s.JPG. Permission is granted for reproduction and use of images for non-profit research and educational purposes.

Fig. 7d. Second-to-top compartment on the right of the central portal, showing a figure with what seems to be a pilgrim’s staff. Source: “Peoples on Tympanum of Central Portal in Narthex” created by G. David Donahue, July 1997, part of the “Images of Medieval Art and Architecture” project © Alison Stones, taken from https://www.medart.pitt.edu/image/france/france-t-to-z/vezelay/portals-sculpture/Central-portal/Peoples/vezport011b.jpg. Permission is granted for reproduction and use of images for non-profit research and educational purposes.

The Author

Minha Park is a Fine Arts student pursuing a Bachelor of Arts at HKU.