The Reliquary of Sainte Foy

Introduction

Foy (or Faith in English) was a young woman who lived in Agen in southwestern France. Widely known as a virgin martyr, Foy was a very popular saint across the Middle Ages.

Sainte Foy: Who Was She?

Sainte Foy’s life was cut short during the Roman persecution of Christians in the fourth century.1 After being arrested, Foy refused to surrender to the Romans even under torture, exhibiting her exemplary faith and religious devotion to Christianity. As written in the Passio (The Passion of Sainte Foy), when Foy was summoned before a Roman prefect,

she prayed to the Lord, saying, ‘Lord Jesus Christ, You Who always aid Your own in every circumstance, be present now with Your handmaiden and supply acceptable words to my mouth, which I may give in answer before this tyrant.’ And she armed herself with an unconquerable shield, making the sign of the holy cross on her forehead, mouth, and heart, and so she went on with her spirit strengthened.2

Even as she was threatened, Foy’s faith did not waver; filled with holy strength, she exclaimed: “For the name of my Lord Jesus Christ I have been prepared not only to be threatened but to suffer all kinds of torments.”3

Unfortunately, Foy was then tortured to death with a red hot brazier (a pan for coals) and beheaded, at only twelve years of age. Her body was then secretly buried; it was only transferred to a basilica built at the site of her martyrdom two centuries later.4 According to the Passio,

She was the first in the city of Agen to receive the crown of a martyr’s Passion; she was its glory and its model of a great martyr (…) both in her understanding and her actions she seemed to have the maturity that belongs to advanced age. She was beautiful in appearance, but her mind was more beautiful.5

Foy has been listed as Sainte Foy, “Virgin and Martyr,” in the martyrologies, with her feast day occurring on October 6.6 Nonetheless, the details of Foy’s life remain largely unknown even until today, as most records about her were made after her death.

The Holy Theft

The reliquary of Sainte Foy was originally located in a monastery in Agen. In the eighth century, a group of monks (who would later establish the Abbey Church of Sainte-Foy) fled from Spain to Conques, France, hoping to escape from the Saracens (Arab Muslims).7 At the time, Conques experienced a decline in power as King Pippin I ordered the construction of a new monastery at Figeac, located about forty kilometers north and west of Conques.8 Under such circumstances, “Conques needed a power base of its own in order to maintain its independent existence, and the appropriate power base in the ninth century was a miracle-working saint”;9 as Gobin notes, “These attempts were not always committed in the most Christian ways, but rather through deception and theft,”10 also known as furta sacra.

The common belief was that a saint’s reliquary could not be relocated without the saint’s permission; hence, a successful move was seen as indubitable evidence of a saint’s willingness to be relocated. In the case of the relic of Saint Foy, a monk sent from Conques joined the monastery in Agen and played the role of an ordinary faithful brother, quietly waiting—for ten years—for the right time to steal the relic.11 The monk was appointed “guardian of the church’s treasure, including of course Saint Foy’s tomb”;12 he then successfully retrieved the head of Sainte Foy, possibly on January 14, 866.13 Conques’ acquisition of Sainte Foy was recorded in the Translatio and naturally resulted in a shift of the cult’s religious base from Agen to Conques.14 Despite Agen’s various efforts to reclaim the Foy’s relics, it eventually acknowledged her translation.15 Conques then emerged as a major stop on the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela in Spain as the cult of Sainte-Foy spread from Conques to Spain.16

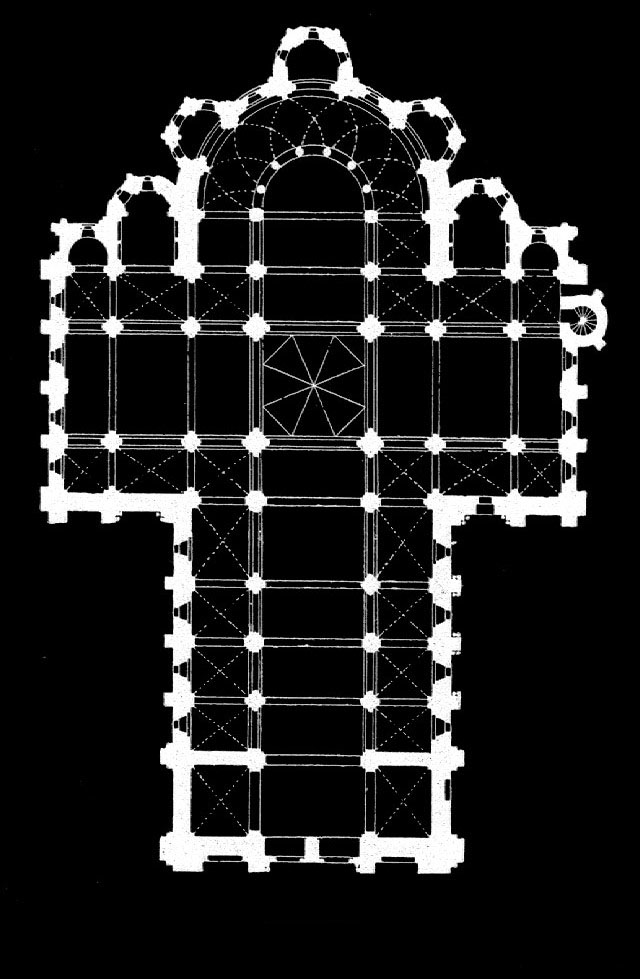

Consequently, Conques began to receive an influx of pilgrims, reaching its peak in the eleventh century when “pilgrims made Conques the goal of their journeys.”17 As Kathleen Ashley and Pamela Sheingorn point out, diverse groups of visitors frequented Conques, including “nobles, peasants, and prisoners.”18 To accommodate the increased flow of visitors, the church of Conques was expanded under the direction of Abbot Odoric and was completed in around 1120.19

The Abbey Church of Sainte-Foy

Click here to take a virtual tour of the church.

What is especially remarkable about the newly constructed church is its Romanesque features, including barrel vaulting, a projecting transept, and radiating chapels. The church consists of “three majestic towers project into the heavens atop a single, two-part elevation, and a barrel-vaulted nave culminating with chapels radiating from its east end,”20 effectively evoking a sense of awe and respect in pilgrims and visitors as they approach the building. The adoption of Romanesque architectural forms provides insight into the increase in pilgrimage and religious practices in the medieval age.

This church plan in fact adheres to a general design that is shared between a number of Romanesque pilgrimage churches, and reflects how architectural innovations might have arisen out of the need to accommodate pilgrims. Historically the Abbey Church of Sainte-Foy has been connected to a group of churches that includes the Basilica of Saint Martin at Tours, the Abbey of Saint Martial at Limoges, the Basilica of Saint-Sernin at Toulouse, and finally, the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, with scholars noting similar features between them such as fireproof stone vaulting, an apse with ambulatory and radiating chapels, and enlarged crypts.21 The new layout of the church ensured adequate space for all the visiting pilgrims (see fig. 3): “Using the side aisles and ambulatory, pilgrims could progress through the church to view, through the protective iron grillwork, the reliquary-statue reigning over the choir. They could also crowd into its spacious nave and transepts for special occasions such as the saint’s feast day.”22

When one travels to the west door of the church, they come across a great tympanum that depicts the Last Judgment (see fig. 4). Examining this piece more closely, Sainte Foy can be found on the right side of Christ, representing heavenly peace and harmony (as opposed to the atrocities of hell on the opposite side). This scene specifically portrays the hand of God recognizing Sainte Foy as an intercessor (see fig. 5).23

The Reliquary of Sainte Foy

Watch this video to imagine the sensory experience of venerating the reliquary-statue of Sainte Foy. Historiens de l’Art Migrateurs, “St Foy Révélée,” Centrum Raně Středověkých Studií, Masarykova Univerzita, 2017.

The relics of Sainte Foy “were enclosed in the head” of the reliquary-statue of Sainte Foy (fig. 6), now located in a small treasury museum in the west gallery.24 The original statue was in fact quite different from what we see today: it represented “the saint seated in a stiff, frontal posture” and only had a “cylindrical projection” in place of a head.25 The gold head, portraying an adult male, was speculated to have come from an imperial sculpture of the fifth century and was likely a royal donation.26 After the miracle of Guibert (see the section on Sainte Foy’s miracles for details) and with the help of various donations that came thereafter in the late tenth century, the statue was modified to the basic form of what we are familiar with today: “a crown, ecclesiastical garb, and a throne.” (figs. 7-8)27

The reliquary is also thoroughly sheathed in gold and adorned with a number of gems, emanating a sense of the sacred and unearthly, yet it is physically present in front of the viewer’s eyes. These statues, known as “majesties,” which enshrine relics in three-dimensional forms, “blurred the distinction between image and reality, between memory and presence,” allowing the viewer to experience the saint as an actual living being “who could hear and see them and, most important of all, could grant their petitions.”28 As Gobin remarks, this “[adheres] to the theory that the more elaborate the reliquary is, the more significant the relic is within: the reliquary becomes a relic itself.”29

The glorious appearance of the reliquary can be seen as a representation of the sacred powers of the relic within. The golden statue at times took on the power of the saint that it represents, since although the saint usually appeared in miraculous visions as a little girl, she sometimes took the form of her statue as well.30 In other words, there is a construction of meaning and significance through the form of the reliquary; ultimately, the line between the reliquary and the saint herself is blurred, and the two become one.

The Miracles of Sainte Foy

Sainte Foy was believed to be one of the most powerful saints in medieval history. She had the “ability to not only heal the sick (primarily eyesight … ) but could raise the dead, and break the chains of the enslaved.”31 She protected the good and punished and haunted the evil, sometimes even causing physical harm to those who refused to submit to her.

One of her most famous miracles was the miracle of Guibert, which involved Sainte Foy restoring a man’s injured eyes, possibly occurring in 983; the man was thereafter known as Guibert the Illuminated.32 The miracle “stimulated a great flood of donations, grants of land and churches, which enabled the creation of a new golden altar frontal.”33 Interestingly, the sources of donations seem to have undergone changes over the years:

Through the mid-eleventh century, it was the local castellans, feudal tenants, and peasants who made Conques wealthy. After 1065, the donors were people of power and authority—bishops and archbishops, counts and countesses, even kings—and represented a wide geographical distribution.34

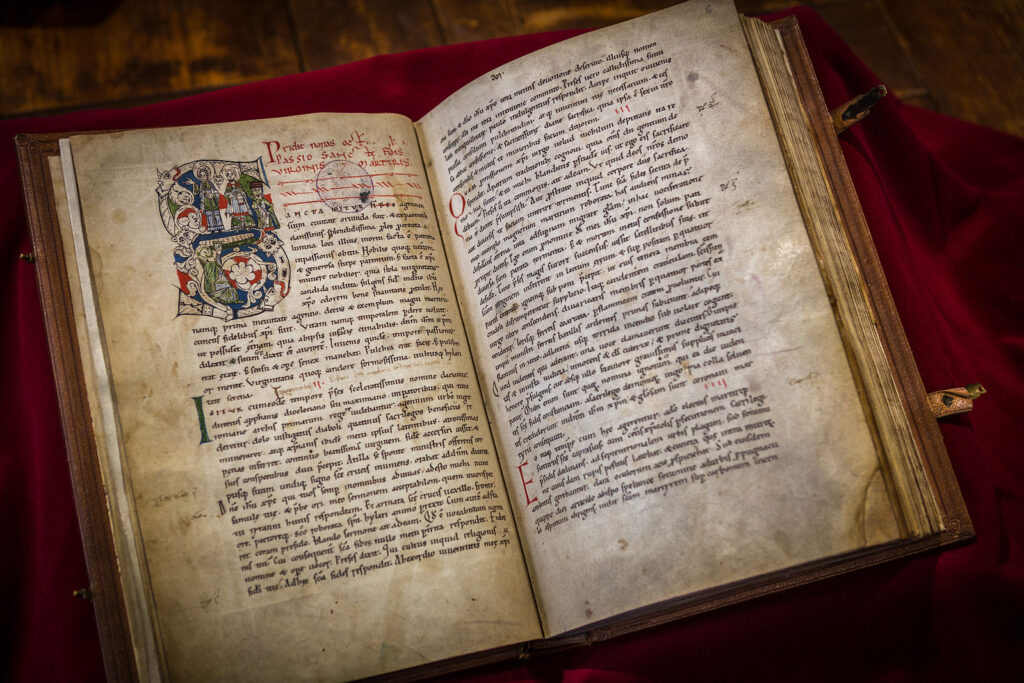

For instance, the treasury in which the reliquary is located today includes a number of donations from royalty: there are over twenty sumptuous reliquaries, including the golden Reliquary of Pippin and mysterious A of Charlemagne.35 This suggests that the church’s influence expanded beyond the bounds of religion into the political field; these donations could also be interpreted as a royal endorsement of the church, which likely further elevated its status. Additionally, Foy’s miracle-working powers attracted Bernard of Angers, who made repeated pilgrimages to Conques and recorded the miracles he had witnessed in what would become known as the first two books of the Book of Sainte Foy’s Miracles (see fig. 9).36 Bernard then contributed to the reputation of the church and Conques by spreading his records in northern France.37

Over time, Sainte Foy received substantial tributes from her devotees and pilgrims for her powerful miracles. Even today, the church and the reliquary of Sainte Foy continue to welcome those who wish to witness the saint’s glory to its fullest. Additionally, annual processions on Sainte Foy’s feast day in October still take place regularly.

Bibliography

Ashley, Kathleen and Sheingorn, Pamela. “An Unsentimental View of Ritual in The Middle Ages or, Sainte Foy Was No Snow White.” Journal of Ritual Studies 6, no. 1 (1992): 67.

Geary, Patrick J. Furta Sacra: Thefts of Relics in the Central Middle Ages. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Gobin, Sydney K. “The Cult of Saints: Sainte Foy.” The Medieval Magazine, May 8, 2019. https://www.themedievalmagazine.com/past-issue-features/2019/5/8/the-cult-of-saints-sainte-foy-by-sydney-k-gobin (accessed Apr. 4, 2020).

Remensnyder, Amy. “Legendary Treasure at Conques: Relics and Imaginative Memory.” Speculum 71, no. 4 (1996): 884–906.

“Romanesque Architecture.” Encyclopedia Britannica. August 21, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/art/Romanesque-architecture (accessed Apr. 4, 2020).

Sheingorn, Pamela. The Book of Sainte Foy. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995.

Vernon, Eleanor. “Romanesque Churches of the Pilgrimage Roads.” Gesta, Pre-Serial Issue (1963): 12-15.Ward, Benedicta. Miracles and the Medieval Mind: Theory, Record, and Event, 1000-1215 Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. 1987.

Image Credits

Header Image. Reliquary of Sainte Foy, ca. 1000 with later additions, Church of Sainte-Foy in Conques, France. Photograph © E. Lastra.

Fig. 1. Abbey Church of Sainte-Foy, Conques, France. Photograph © E. Lastra.

Fig. 2. Abbey Church of Sainte-Foy from the west, Conques, France. Photograph © E. Lastra.

Fig. 3. Plan of the Church of Sainte-Foy. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Abbatiale_Sainte-Foy_de_Conques_plan_01.jpg. Modified image in the public domain.

Fig. 4. Last Judgment Tympanum, Church of Sainte-Foy in Conques, France. Photograph © E. Lastra.

Fig. 5. Sainte Foy kneeling before the hand of God, Last Judgment Tympanum, Church of Sainte-Foy in Conques, France. Photograph © E. Lastra.

Fig. 6. Reliquary of Sainte Foy, ca. 1000 with later additions, Church of Sainte-Foy in Conques, France. Photograph © E. Lastra.

Fig. 7. Reliquary of Sainte Foy, ca. 1000 with later additions, Church of Sainte-Foy in Conques, France. Photograph © E. Lastra.

Fig. 8. Reliquary of Sainte Foy, ca. 1000 with later additions, Church of Sainte-Foy in Conques, France. Photograph © E. Lastra.Fig. 9. Livres des miracles de Sainte-Foy, La Bibliothèque Humaniste de Sélestat, France. Photograph by Claude Troung-Ngoc, January 21, 2014. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Biblioth%C3%A8que_humaniste_de_S%C3%A9lestat_21_janvier_2014-117.jpg, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

The Author

Emily Su is a Taiwanese student majoring in Economics and Philosophy at HKU. She is also an avid art lover who enjoys studying Fine Arts.