The Veronica: Enacting the Virtual and the Physical

Introduction

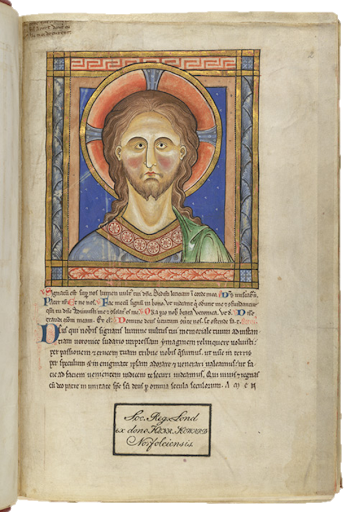

The Veil of Veronica in Rome (fig. 1), or simply the Veronica, has consistently been one of the most popular relics of the Middle Ages whose association with Christ and well-documented legends have attracted a ceaseless stream of pilgrims at least since the twelfth century. The relic’s sui generis nature of being an acheiropoieton, an image made without hands, has opened up a dynamic body of research that discusses the relic’s inherent tensions: some focus on the reproducibility and substitutability of the Veronica as a holy image and the decentered pilgrimage experience that it has created, while others study the appropriation of the Veronica’s reproductions for the purpose of augmenting the appeal of the original.

This page aims to investigate the conflicts created by the two aforementioned medieval usages of the Veronica’s reproductions. Special attention will be given to the relic’s conduciveness to reproduction, the notion of a decentered pilgrimage, the malleability of the literary tradition supporting the cult of Veronica, and finally the Church’s role in the appropriation of the legend to its own advantage.

The Evolution of the Legend of St. Veronica

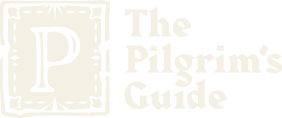

Virtually all of the apocryphal legends of St. Veronica were inspired by the story of the Haemorrhoissa from the synoptic gospels, in which an anonymous woman with “an issue of blood” was healed after merely touching Christ’s garment.1 Despite being only a minor episode in the ministry of Christ, this story and the theme of Christ’s miraculous healing through his garment was picked up in subsequent Christian writings of late antiquity, such as the ca. fifth-century Acts of Pilate, the ca. seventh-century Cura sanitatis Tiberii, and the eighth-century Vindicta Salvatoris.2 These prototype-legends vary greatly in their plots, but they all involve a certain Veronica, or Beronikē in Greek, personally acquiring the sudarium (shroud) of Christ during one of his peaceful ministries and subsequently using it to heal foreign rulers.3 Hence, most depictions of the Veronica in the early Middle Ages show the face of a peaceful Christ (figs. 2, 3).

Fig. 3 (right). Christus Acheiropoietos (The image of Christ made without hands), Vladimir Susdaler School, mid-12th century, egg tempera on wood, 77 × 71cm, originally from the Assumption of Mary Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin, now preserved in the Tretjakov Gallery, Moscow.

Remarkable here is the early Christian writers’ identification of the unknown woman in the gospel as Veronica and their fictional elaboration of the legend of the sudarium and its healing powers. It is important to note that no scholar has yet established any link between the sudarium with the Passion. Therefore, all vernicles (badges depicting the shroud) produced during the early Middle Ages show a tranquil face of Christ without exception. But this started to change from the thirteenth century onwards, during which time the church increasingly attempted to harness the power of and the benefits brought by the cult of St. Veronica through its claim of ownership of the vera icon.

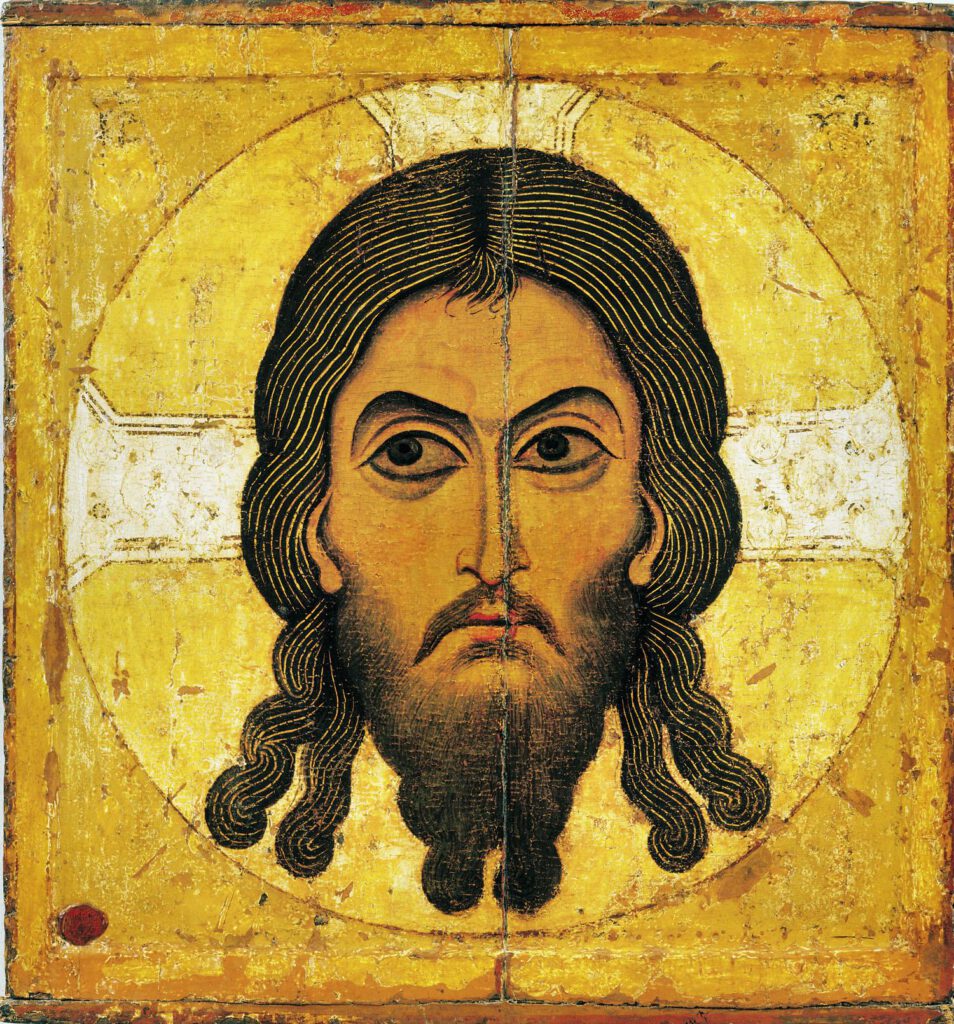

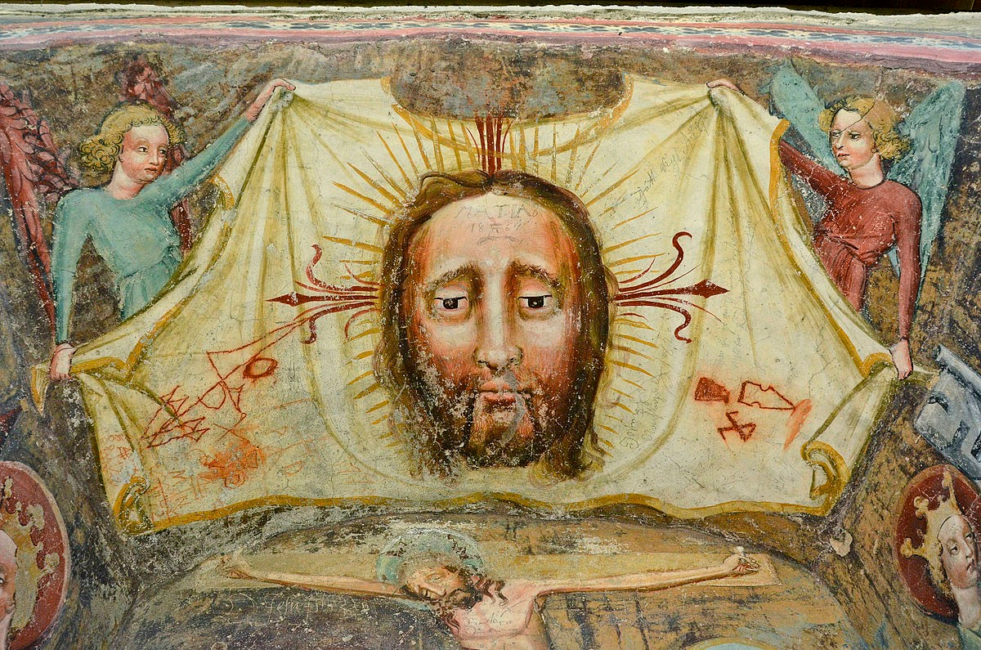

The final linkage of the legend of Veronica to the Passion was eventually furnished by the thirteenth-century La Grant Estoire dou Graal.4 Here, the location of Veronica’s acquisition of the sudarium has been moved to the via Dolorosa. It narrates that on Christ’s way to Golgotha for crucifixion, he specifically required that Veronica use the cloth, which she originally meant for sale, to wipe his face, leaving not only the impression on the cloth of the Christ’s face, but also that of the crown of thorns and blood stains. As a result, the vernicles produced from the late thirteenth century onwards started to show not necessarily the face of a tranquil Christ, but one that is undergoing the Passion (figs. 4, 5).

The Nature and Appeal of the Veronica

The popularity of the Veil of Veronica can be attributed to its unique nature among other relics as an acheiropoieta. Christ’s face, the crown of thorns, and his blood miraculously left an impression on Veronica’s sweat cloth, an image that was not created by the hands of Veronica, but by the divine power of Christ. Unlike other relics of bodily remains and objects in association with saints, the Veil of Veronica fulfilled people’s desire to have Christ’s visual presence before them. The salvific power of a face-to-face encounter with Christ is even evident in the Bible:

For God … hath shined in our hearts, to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God, in the face of Christ Jesus. (2 Corinthians 4:6)5

The mimetic quality of the Veronica made this experience possible for medieval audiences. In fact, the pilgrimage to the Veronica was one of the most popular pilgrimage routes throughout the Middle Ages.6 Since the sanctity of the Veronica lies in its imagehood, it shows a potential to be reproduced without disruping its divine imagehood. That said, pictorial translations inevitably introduce nuances. The gaps between the copies and the original have generated new meanings and understandings.7

Decentering Pilgrimages

Pilgrimages to the Veil of Veronica were extremely popular and deemed important in the Middle Ages.8 Pilgrims going to Rome could take back a vernicle—a badge with the sudarium depicted upon it—as a proof of their journey to Rome. Vernicles are not only the validation of one’s physical journey to Rome to gain indulgences, but also one’s proof of spiritual ascendance after the pilgrimage. They imply not only the bodily, but also the spiritual voyage for redemption.9 This fifteenth-century copper vernicle (fig. 6) exemplifies the conventional design of a vernicle, depicting the orthodox representation of the Holy Face with the Latin inscription “salve sante facies nostris redeptori” (Hail, the holy face of our redeemer). Other than evoking the embodied experience of pilgrimage, the vernicle somehow acts as a substitute for the Veil of Veronica, and its divine power, by merely bearing the image of the Holy Face. The Latin-inscribed prayer also closes the gap of representation by inducing the spiritual quality of the Veil of Veronica via the redemptive prayer dedicated specifically to the Holy Face.10

If the vernicle badge became a crystallization of the sudarium that implied the physical and spiritual journey one experienced during their long travel to St. Peter’s despite spatial and temporal boundaries, then Matthew Paris’s drawing of the Holy Face would even further complicate the need and effect of conducting a long journey to Rome. It is the Arundel Veronica (fig. 7) in the Arundel Psalter, attributed to Paris, that illustrates the Holy Face. It was paired with prayers from psalms that emphasized the salvific quality of Christ’s “sign” and “face,” and the transformative power of Christ’s face and its effects on one’s soul.11 What is more, on the page facing this Arundel Veronica, Paris remarked,

the face of the Savior is here depicted by the work of the artist in order that the soul may dedicate itself to devotion.12

Validated with the referenced biblical texts, this remark addresses the Arundel Veronica’s ontological nature, surprisingly, not as an acheiropoieta, but as a true image although it is painted by the artist himself. In Paris’s view, a faithful depiction would bear equal significance to the Holy Face, just as a seal’s impressions would be all deemed authoritative. This not only sheds light on the reproducibility of the Holy Face, but it also shifts our focus from the materiality of the Veronica, or how it is made, into the religious implication of the image. The physical journey to St. Peter’s seemed redundant to Paris, as the importance of the sudarium does not lie in the physical veil, but in the imprinted Holy Face that could now be witnessed in Paris’s drawing and various other depictions. This separates the spiritual gain of a pilgrimage (which is witnessing the sudarium) from the physical journey to St. Peter’s Basilica. This profoundly disputes the traditional pilgrimage experience, as it spatially abstracts the whole experience from Rome and dislocates it anywhere anytime, transforming the Veronica from a site-oriented experience to a viewer-centered experience that could happen virtually anywhere and anytime.Although medieval visual copies always claimed to be legitimate, faithful representations, their accuracy of form is far less important than their spiritual connotations.13 These copies are not accurate quotations but devices to communicate the saintly authority of the prototype.14 Reproductions like the Arundel Veronica were meant to recall and refresh people’s imagination who had visited the Veronica and, at the same time, convey the distant holiness to viewers who had not seen the Veronica in person. The Arundel Veronica ultimately forms an epistemological route that connects the viewers to Rome. If one also considers the various acheiropoieta relics of the true image of Christ, this forms an even larger ontological network that allows viewers to roam spiritually.

The Church’s Intervention and Appropriation

The first record of the church’s possession and public display of the sudarium came in 1000, when the relic was described to be housed in the oratory of Pope John VII in Old St. Peter’s, and by the end of the twelfth century it was placed inside a ciborium (a chalice-like receptacle) for public veneration in the selfsame chapel (fig. 8).15 The thirteenth century saw a series of campaigns by successive popes to associate the cult of St. Veronica with the Passion of the Christ. First in 1208, Pope Innocent III organized a procession of the relic by the canons from Old St. Peter’s to the hospital of Santo Spirito.16 And, after expounding definitively the dogma of transubstantiation in the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, the church went on to further incorporate the image in the scheme of eucharistic redemption: the first ever Feast of Corpus Christi, instituted by Pope Urban IV in 1264 to celebrate the presence of Christ and during which Christ’s relics were lavishly displayed and venerated, featured the sudarium heavily.17 Utilizing the association of the sudarium with the Passion, one that has been made vivid in popular imagination through tireless papal initiatives, the church endorsed and affirmed Veronica’s proper role in Christian hagiography and liturgy.

By endorsing the view that the sudarium had been produced during Christ’s journey to the Cavalry and not, according to earlier accounts, during one of Christ’s earlier peaceful ministries, the church has irrevocably tied Christ’s Passion, his redemptive journey for all mankind, with the personal redemptive journey of pilgrimage. In other words, the late medieval pilgrimage to see the icon in Rome has been construed to resemble Christ’s arduous journey. A second tier of spiritual parallel was then also drawn between the ultimate fruit of Christ’s journey—salvation for all—and the indulgence offered to the pilgrims at the end of the journey to Rome.18 It is easy to see why the Passionized Veronica gained widespread appeal from the late thirteenth century onward: this kind of religiously emotive visual stimulus sat well with the then dominant Franciscan discourse that encouraged poverty, meditation, and pilgrimage.19 This culminated in the Franciscan Pope Nicolas IV’s proclamation that Veronica was a more important relic than even St. Peter’s tomb.20

In addition, given the sacred role Christ’s blood played in both the Eucharistic mysticism in scholastic circles and the masses for laymen, a new depiction of the Holy Face in vernicles that shows a bloodied, suffering Christ served to emphasize Christ’s blood’s miraculous properties. Having long established its monopoly on the administration of the process of transubstantiation, the late medieval church effectively appropriated the power of the sudarium for its own entrenchment.

Since the medieval church controlled the consumption and display of the Vatican Veronica, by extension they also had authority over the visual translation and dissemination of the veil.21 For example, Paris’s Arundel Veronica, created in 1240, is based on the papally sanctioned image of the original Veronica and the accompanying prayer: the Vatican Veronica rotated itself 180 degrees during a procession led by Pope Innocent III in 1216. Judging it to be a bad omen, he immediately ordered the public veneration of the Veronica and commissioned an image of it with an official prayer.22

Conclusion

This page has surveyed the literary tradition of the cult of Veronica with specific focus on its malleability, which has made it susceptible to multiple subsequent appropriations. The appeal of enabling a face-to-face encounter with Christ has elevated the Veronica from other relics and suggests its potential reproducibility. This is further affirmed in the various reproductions of the Holy Face, such as the vernicles and Matthew Paris’s book. They reminded medieval viewers not only of the physical pilgrimage they could have or had conducted, but also a decentered spiritual pilgrimage via contemplating the nature of the Veronica, forming a mental network of pilgrimage routes that connected viewers to all the images of the Holy Face.

(Above) A map locating the distribution of the reproductions of the Holy Face in Europe, the Mediterranean and Western Asia, created by https://veronicaroute.com/. Zoom in and click on the icons to explore.

This stands in stark contrast with the church’s appropriation and monopoly of the Veronica with the intention to evoke an intense religiosity and the physicality of the original image. The tensions inherent in the nature of the Vatican Veronica have inspired two very divergent responses of appropriation. The physical and virtual possibilities of the relic have propelled it into the forefront of medieval pilgrimage studies. This article hopes to contribute to the unfortunately understudied aspects of “alternative pilgrimages” and reflect on the conventional physicality discussed in pilgrimage studies.

Link to Useful Website

https://veronicaroute.com/ (An online catalog of the reproductions of the Holy Face from the year 1000 to the present day).

Bibliography

Blick, Sarah, and Laura Deborah Gelfand. Push Me, Pull You. Studies in Medieval and Reformation Traditions. Leiden: Brill, 2011.

Bolton, Brenda M. “Quifldelis est in mínimo: The Importance of Innocent III’s Gift List.” In Pope Innocent III and his World, edited by Moore, John. London: Routledge, 2016.

Cura Sanitatis Tiberii, translated by Tuomas Levänen. www.academia.edu/15436621/Cura_Sanitatis_Tiberii_English_Translation.

Heullant-Donat, Isabelle. “Martyrdom and Identity in the Franciscan Order (Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries).” Franciscan Studies 70 (2012): 429-53.

McKitterick, Rosamond, John Osborne, Carol M. Richardson, and Joanna Story. Old Saint Peter’s, Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Molinari, Andrea Lorenzo. “St. Veronica: Evolution of a Sacred Legend.” Priscilla Papers 28 (2014): 10-16.

Nitze, William A. “Messire Robert De Boron: Enquiry and Summary.” Speculum 28, no. 2 (1953): 279-296.

Ousterhout, Robert. “”Sweetly Refreshed in Imagination”: Remembering Jerusalem in Words and Images.” Gesta-International Center of Medieval Art 48, no. 2 (2009): 153-68.

Rhodes, James F. “The Pardoner’s “Vernycle” and His “Vera Icon”.” Modern Language Studies 13, no. 2 (1983): 34-40.

Rosser, Gervase. “Turning Tale into Vision: Time and the Image in the “Divina Commedia”.” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 48 (2005): 106-122.

Sand, Alexa Kristen. Vision, Devotion, and Self-representation in Late Medieval Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Spencer-Hall, Alicia. Medieval Saints and Modern Screens: Divine Visions as Cinematic Experience. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2018.

Van Dijk, Ann. “The Afterlife of an Early Medieval Chapel: Giovanni Battista Ricci and Perceptis of the Christian past in Post-Tridentine Rome.” Renaissance Studies 19, no. 5 (2005): 686-98.Vettori, Alessandro. “Veronica: Dante’s Pilgrimage from Image to Vision.” Dante Studies, with the Annual Report of the Dante Society, no. 121 (2003): 43-65.

Image Credits

Fig. 1. A canon of St. Peter’s holding up the sudarium during the ceremony celebrating the Fifth Sunday of Lent, screenshot. Accessed on April 15, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7BceFgXa3Ww&t=2s.

Fig. 2. Icon of Abgar of Edessa Holding the Sudarium, St. Catherine’s Monastery, Mount Sinai, ca. tenth century. Photograph by Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Saint Catherine, Egypt. Source: Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image_of_Edessa#/media/File:Abgarwithimageofedessa10thcentury.jpg, accessed on April 15, 2020. Public domain.

Fig. 3. Christus Acheiropoietos (The image of Christ made without hands), Vladimir Susdaler School, mid-12th century, egg tempera on wood, 77 × 71cm, originally from the Assumption of Mary Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin, now preserved in the Tretjakov Gallery, Moscow. Photograph bythe Tretjakov Gallery. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Christos_Acheiropoietos.jpg#/media/File:Christos_Acheiropoietos.jpg. Public domain.

Fig. 4. Cycle de la Passion en dix tableaux (Le portement de croix avec Véronique), Heinrich Lutzelmann, 1485, oil on panel, Eglise Saint-Pierre-le-Vieux catholique, Strasbourg. Photograph by Ralph Hammann. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:StPierreVieuxC12.JPG#/media/File:StPierreVieuxC12.JPG. Public domain.

Fig. 5. Veil of Veronica, ca. 1430. Vault of Kernmaier-Kreuz newsstand at Sankt Walburgen, Austria. Photograph by Johann Jaritz. Source: Wikimedia Commons, accessed on April 15, 2020, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Eberstein_Sankt_Walburgen_Kernmaier-Kreuz_Alkovenmalerei_Acheiropoieton_18032014_044.jpg. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 AT.

Fig. 6. Anonymous, the Vernicle, or the Veil of Veronica, copper alloy, ca. fifteenth century. Museum of London (Object ID: 88.9/18), London, United Kingdom. Source: Museum of London, accessed on April 15, 2020, https://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/online/object/31308.html. Fair dealing use of images applicable to non-commercial research.

Fig. 7. Attributed to Matthew Paris, Veronica, England, ca. 1240. London, British Library MS Arundel 157, fol. 2r. Photo © The British Library Board. Accessed on April 15, 2020, http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=arundel_ms_157_fs001r.

Fig. 8. Ciborium in the Oratory of John VII, from Giacomo Grimaldi, Instrumenta, 1620. Vatican Apostolic Library, Vatican City. Published in Rosamond McKitterick, John Osborne, Carol M. Richardson, and Joanna Story, eds., Old Saint Peter’s, Rome (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 238. The publication of Old Saint Peter’s Rome is in copyright, © The British School at Rome2013, and subject to statutory exception, which, according to the UK Intellectual Property Office, includes non-commercial research.

Mini-Papers Download

Veronica in the “Age of Pilgrimage.”

Universalization of the Veil of Vernonia.”

The Authors

Kevin Lam is a Fine Arts student and art-enthusiast from Hong Kong who is interested in exploring identity, phenomenological experiences of art, and their relationships with society across geographies and times.

A final-year student majoring in Fine Arts, Charlie Lee’s research area includes Western medieval and pre-1800 art and architecture.