Votives, Pilgrims, and Power: The Miracle Windows As the Mirror of the Popular at the Canterbury Cathedral

Introduction

Imagine a single light source in a cathedral, shining through an elongated stained-glass window along the side of a wall. The bright colors and detailed images of the window contrast with the dark and immense interior of the holy sacred place. The Miracle Windows of Trinity Chapel at Canterbury Cathedral speak to those who enter, telling the miracle stories of those who came before them and proclaiming the power of Saint Thomas Becket.

The Miracle Windows are a group of stained-glass window panels; they depict a group of miracles from the Miracles of St. Thomas of Canterbury (The Miracula Sancti Thomae Cantuariensis; 1171–73), written by Benedict of Peterborough and William of Canterbury. The Miracle Windows are important objects of study because, as recently as 2018, it was discovered that the condition of the group of glass panels was higher than expected. It was originally estimated that the windows only contained 30 percent medieval glass, the panel group actually contains 70 percent of stained-glass pieces from the Middle Ages.1

Watch the above video by Canterbury Cathedral: Dr. Rachel Koopmans (Associate Professor at York University, Canada) and Leonie Seliger (Director of the Cathedral Studios at Canterbury) discuss the discovery of medieval glass in the Cathedral’s Miracle Windows. Jan 17, 2019.

In other words, the windows contain important historical sources that can help us to understand the experience of pilgrimage to Canterbury Cathedral in the Middle Ages. Although some see the Miracle Windows as simply a visual translation of the written text, its representational images highlight the relationship between pilgrims and St. Thomas, the role of the votive as a form of displacement of the power of the church, and the delineation of a communal vision of the pilgrims to Canterbury Cathedral.

“Help Me and I Will Do This for You”

Pilgrims came to visit the tomb and shrine of St. Thomas at Canterbury Cathedral with their own devotions, which they performed with votives that they brought along with them. Votives could be any object or action, so long as it was meaningful to the devotee’s prayer. Votives functioned as a devotional promise made by the pilgrim to a divinity or saint.2 For those who came with worries or demands, such vows were made by those with faith in the saint. In this light, the stories presented on the Miracle Windows served to direct the interaction between the pilgrims and the saint.

For example, panel VII, scene 7 (fig. 1) illustrates the story of The Wife of the Earl of Hertford Retrieving Relics, in which the pilgrim donates a trindle, a large coiled candle, (on the right) and a golden votive crown (hanging above) to the saint. In addition to representing the votives themselves in this prayer scene—as well as the practice of performing these votives—all of the objects in the scene are presented using an enlarging effect as noted by Rachel Koopmans.3 For comparison, the general size of the Becket Limoges reliquaries, likely the reliquary-type to which the wife of the Earl of Hertford prays, are 15 to 25 cm, and therefore the scale of the reliquary was enlarged in the scene.4 The trindle in the wife’s hands as well as the votive crown hanging above also seem enlarged for visibility. Such enlargement of the objects highlights the role of these objects in the occurrence of miracles or, in other words, it underlines the vow made between the pilgrim and the saint. Thus, one who came to view the Miracle Windows in the Middle Ages would have understood the importance of the object to which they prayed, seeking intercession from the saint, as well as that of the votive that they brought.

Canterbury Cathedral. Photo: Mattana, 2011.

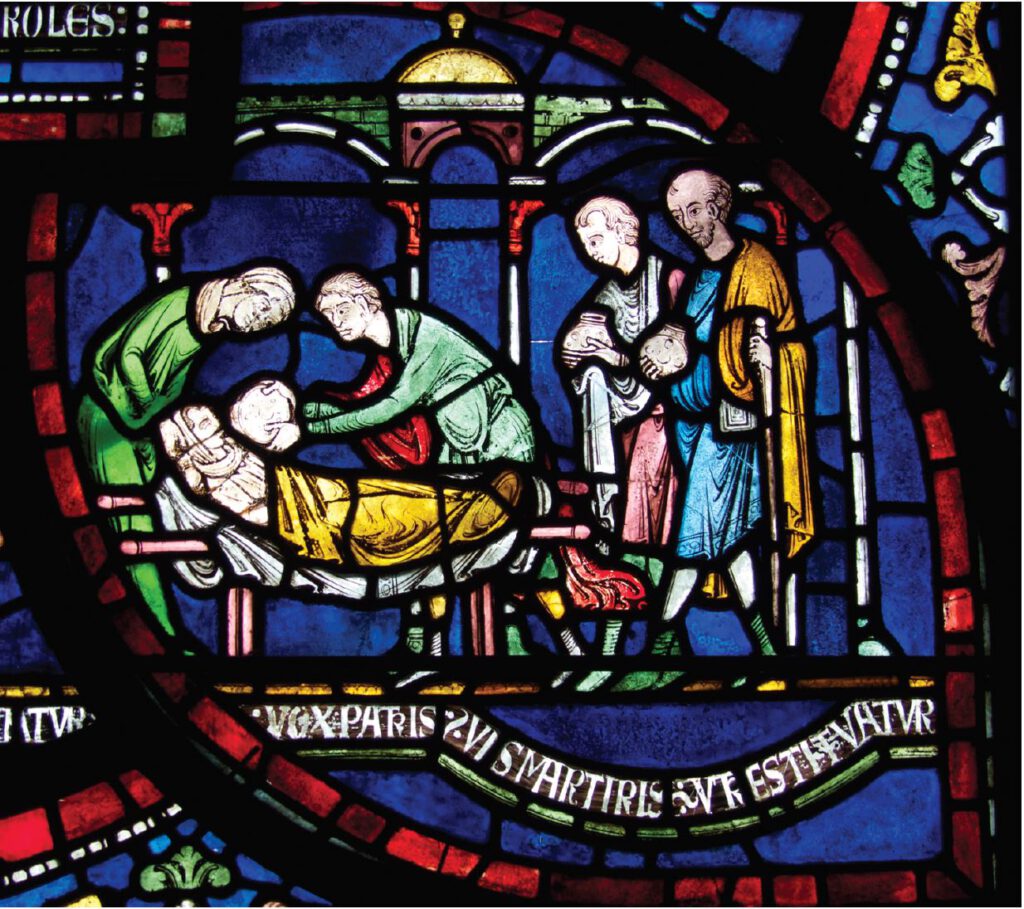

In addition, panel II, scene 11 (figs. 2a-b), illustrates the miracle of Jordan Fitz-Eisulf, in which knight Jordan Fitz-Eisulf hosts pilgrims from Canterbury in his home. When his son got sick and died, the pilgrims gave the boy holy water from the ampullae and the boy came back to life. The ampulla that contains Becket’s holy water, known as “Canterbury water,” is represented in an enormous scale that contrasts with the boy’s head. The large scale of the ampullae on the Miracle Windows, shown almost the size of a human head, contrasts with the surviving Becket ampullae from the medieval period that are only 6 to 7 cm tall.5 The importance of the ampulla and “Canterbury water” will be discussed below, yet, here the ampulla serves as a symbol of the St. Thomas cult and his blessing on its followers.

Canterbury Cathedral. Photo: Jules & Jenny from Lincoln, UK, 2014.

Fig. 2b. Miracle Window, Satined-glass panels. II, ca 1213-20, Canterbury Cathedral. Photo: Gary Ullah from UK, 2014.

These recorded miracles of St. Thomas direct the relationship between the pilgrims and the saint, which is contingent on the vow performed.6 Dana Vasiliu describes the happenings of healing miracles in terms that are almost akin to a transaction: “In most of the cases it involves a double agency and a mutually agreed on manner of conduct.”7 The “double agency” involves the monks, who were supposed to be spiritually perfect so as to be able to administer the use of St. Thomas’s relics, and the ailing recipient who was “pious” and “spiritually sound.”8 This is illustrated in how the wife of the Earl of Hertford presented her devotion with votives and how knight Jordan Fitz-Eisulf was given help from St. Thomas because he kindly hosted the pilgrims. Thus, those who came to the tomb and shrine of St. Thomas at Canterbury Cathedral would understand how they should react and communicate with their saint in order to request help themselves.

The Votives, History, and Power of Canterbury Cathedral

Among the miracle stories presented on the windows, the many luxuries and precious votives stand out. As mentioned above, votives could be any object or action. In contrast to humbler gifts like trindles, a number of the votives left at the tomb and shrine of St. Thomas were jewels, gold pieces, and crowns.9 These luxurious and precious votives demonstrate the popularity of Canterbury Cathedral. Although the tomb needed to be cleared for more pilgrims and their votives, these precious objects were honored by being kept separately, and they were later used as decoration for a new shrine.10 Although that new shrine was destroyed during the Dissolution of the Monasteries as ordered by Henry VIII, written accounts remark on its sumptuousness—made of gold, studded with gems and pearls, and “even crowned with a regal diadem.”11 To think that pilgrims’ votives helped create such a marvelous object that dazzled fellow pilgrims’ eyes; not only that, but their personal votives ended up being the closest that was possible to the saintly relics of St. Thomas. Moreover, the beauty of these luxurious votives can be seen on the Miracle Windows, where they were displayed for new pilgrims and served as a displacement of the power of the church.

The experiences of the earlier pilgrims served as the ultimate evidence of and inspiration for the power or St. Thomas. In light of the Miracle Windows as a visual translation of the Miracles of St. Thomas of Canterbury, one can see a shift from textual to visual, from typology to memory, and from the elite to the popular.12 Anne Harris highlights the fact that although textual sources of Becket’s miracles abounded from the beginning of the cult and probably also flowed into oral traditions, they still were primary written by and targeted at an elite, literate audience, and employ metaphorical languages that are usually steeped in patristic and exegetic traditions.13 Contrastingly, the miracle stained glass windows “prompt the worshippers to envision the saint as present in their own space.”14 That the windows depict pilgrims and other benefactors of Becket’s miracles must surely have seemed to the visiting pilgrims that their presence was acknowledged, and would have, perhaps, made them more conscious of their own bodily experience at the cathedral during their visits. As Harris demonstrates with the window of the Cure of Mathilda of Cologne, the figural repetition of Mathilde within the carefully constructed pictorial space “instill a kind of physical memory in the viewer.”15 We may imagine that, after their visits, the name “Becket” or “Canterbury” would not just elicit a conception of the saint or the site of the cult, but the vivid memory of their own somatic experiences inside that space, when they had once directly encountered with the saint.

Photo: Royal Institution of Cornwall, Anna Tyacke

Fig. 3b. Ampulla with lombardic ‘T’ representing the cult of St Thomas of Canterbury (back), ca. 1400.

Photo: Royal Institution of Cornwall, Anna Tyacke

Fig. 3c. Detail of Fig. 1b. Ampullae with Saint Water from Canterbury.

Aside from the images of luxurious votives and of miracles, highly symbolic ampullae and also other everyday objects were also included on the Trinity Chapel windows. Vasiliu identifies most of the objects depicted on the stained-glass as containers or vessels, with ampullae being a prominent example.16 “The explanation is very simple,” she goes on to say, “The most powerful relic associated with Thomas Becket was his blood which the monks at Canterbury collected immediately after the murder”—blood, specifically, to be put into containers and vessels.17 The blood collected immediately after St. Thomas’s martyrdom was indeed recognized as the symbol of Canterbury Cathedral as well as a relic specifically associated with St. Thomas.18 His blood was diluted with water to create the widely distributed “Canterbury water,” in part to ensure that the blood would be virtually infinitely renewable, and in part to avoid any association with Christ’s blood in the Holy Sacrament.19 Since 1171 and through most of the thirteenth century, ampullae containing Canterbury water could be purchased and worn by pilgrims as powerful relics.20 Thus, the ampullae on the Miracle Windows authorized and announced the pilgrims to Canterbury Cathedral, forming a visible community of pilgrimage. Furthermore, the stories from the Miracle Windows do not simply proclaim Canterbury water-filled ampullae as the symbol of Canterbury Cathedral, but they also delineate how St. Thomas would take special care of the people who made the pilgrimage to Canterbury: it was the “pilgrims’ proximity to that blessed man” that mattered more, said Benedict.21

Visualizing the Community

By presenting miracle stories that one might have heard before they began their pilgrimage to Canterbury, the Miracle Windows were the reenactment and physical embodiment of miracles that had happened in the past. The visualization of the stories’ scenes with the actual votives placed in front of the tomb and shrine of St. Thomas served as a reinforcement of the realness of the cult, like a script for pilgrims to follow for how their vow would bring about their own relationships with the saint, how pilgrims in the past had come with demands, and how the present pilgrims were to receive blessings when they left. The Miracle Windows formed a visible and imaginary community of pilgrims, connecting previous visitors and their gifts, in particular the outstanding and famous cases of those who received miracles, with pilgrims in the present bearing votives and actively praying to St. Thomas Becket.

Bibliography

Blick, Sarah. “2. Votives, Images, Interaction and Pilgrimage to the Tomb and Shrine of St. Thomas Becket, Canterbury Cathedral.” Push Me, Pull You, 2011, 21–58. doi:10.1163/9789004215139_023.

——— . “Reconstructing the Shrine of St. Thomas Becket, Canterbury Cathedral.” In Art and Architecture of Late Medieval Pilgrimage in Northern Europe and the British Isles, edited by Sarah Blick and Rita Tekippe, 405-41. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2005.

“Exciting 12th Century Stained Glass Discovery.” Canterbury Cathedral. September 4, 2018. https://www.canterbury-cathedral.org/whats-on/news/2018/09/04/exciting-12th-century-stained-glass-discovery/.

Harris, Anne F. “Pilgrimage, Performance, and Stained Glass At Canterbury Cathedral.” In Art and Architecture of Late Medieval Pilgrimage in Northern Europe and the British Isles, edited by Sarah Blick and Rita Tekippe, 243–81. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2005.

Koopmans, Rachel. “Visions, Reliquaries, and the Image of “Becket’s Shrine” in the Miracle Windows of Canterbury Cathedral.” Gesta 54, no. 1 (March 2015), 37–57. doi:10.1086/679400.

Lee, Jennifer M. “Searching for Signs: Pilgrims Identity and Experience Made Visible in the Miracula Sancti Thomas Cantuarienis.” In Art and Architecture of Late Medieval Pilgrimage in Northern Europe and the British Isles, edited by Sarah Blick and Rita Tekippe, 473–91. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2005.

Vasiliu, Dana. “The Thingness of the Thing: The Role of Everyday Objects in Becket Miracle Windows.” Romanian Journal of English Studies 11, no.1 (2014): 1-6.

Image Credits

Header. Canterbury Cathedral Trinity Chapel Stained Glass, Kent, UK. Source: Wikipedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Canterbury_Cathedral_Trinity_Chapel_Stained_Glass,_Kent,_UK_-_Diliff.jpg, Licensed under Diliff / CC BY-SA 3.0.

Fig. 1 Canterbury, Canterbury cathedral-stained panel n. VII. Source: Wikipedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Canterbury,_Canterbury_cathedral-stained_glass_17.JPG. Licensed under Mattana / CC BY-SA 3.0.

Fig. 2a. Canterbury Cathedral Window n.II detail. Source: Wikipedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Canterbury_Cathedral_Window_n.II_detail_(37163751463).jpg. Licensed under Jules & Jenny from Lincoln, UK / CC BY 2.0.

Fig. 2b. Canterbury Cathedral Window n.II. Source: Wikipedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Canterbury_cathedral_(20812776040).jpg. Licensed under Gary Ullah from UK / CC BY 2.0.

Fig. 3a. Medieval Ampulla (Front). Source: Wikipedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ampulla_(front)_(FindID_833995).jpg. Licensed under Royal Institution of Cornwall / CC BY 2.0.

Fig. 3b. Medieval Ampulla (Back). Source: Wikipedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ampulla_(back)_(FindID_833995).jpg. Licensed under Royal Institution of Cornwall / CC BY 2.0.

Fig. 3c. Detail of Fig. 1b.

Fig. 4. Miracle Window, stained-glass, ca. 1170 – 1220, Canterbury Cathedral Trinity Chapel. Photograph by Jules & Jenny from Lincoln, UK, May 18, 2015. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Canterbury_Cathedral_interior,_Stained_glass_windows_(45774904264).jpg#/media/File:Canterbury_Cathedral_interior,_Stained_glass_windows_(45774904264).jpg. Licensed under CC BY 2.0.

The Author

Emily Leung is a graduate from the University of Hong Kong studying Fine Arts and Hong Kong Studies. Her research interests include both contemporary arts and cultural theories, focusing on postcolonial art movements as well as identity politics in East Asian societies, such as Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, and China in particular.