Where It All Began—A Virtual Medieval Tour of the Church of the Nativity

Introduction

Beginnings and endings are eternal quests for the entity of beings. Spiritual fulfillment, paradoxically, is emphasized through physical matters, acts, and sensations. Pilgrimage, in a way, is born out of this paradox, for although it is a spiritual undertaking, pilgrims do have an earthly destination in mind. Medieval pilgrimages were arduous for the faithful, and both physical and psychological turmoil might have tested the pilgrims’ determination to complete their journeys. Perhaps it is only fair to start with one of the most significant beginnings and endings. The Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem is at once the site of the beginning of Christ’s life—and so arguably where Christianity all began—and near the end of a pilgrim’s long journey to Jerusalem.

Turbulent Times, Turbulent History?

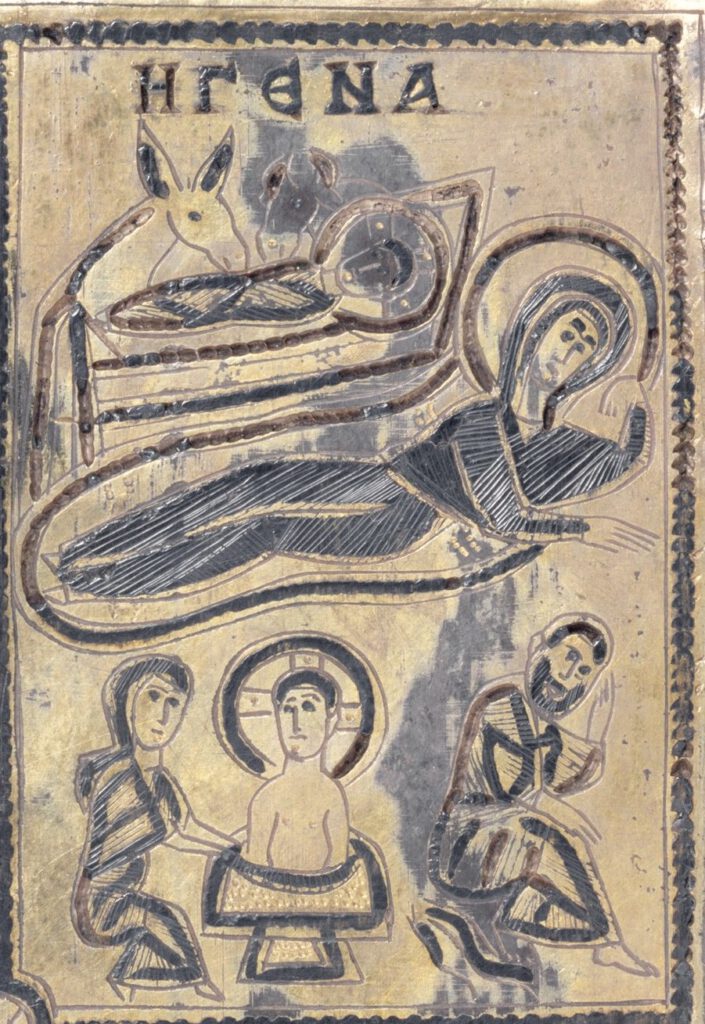

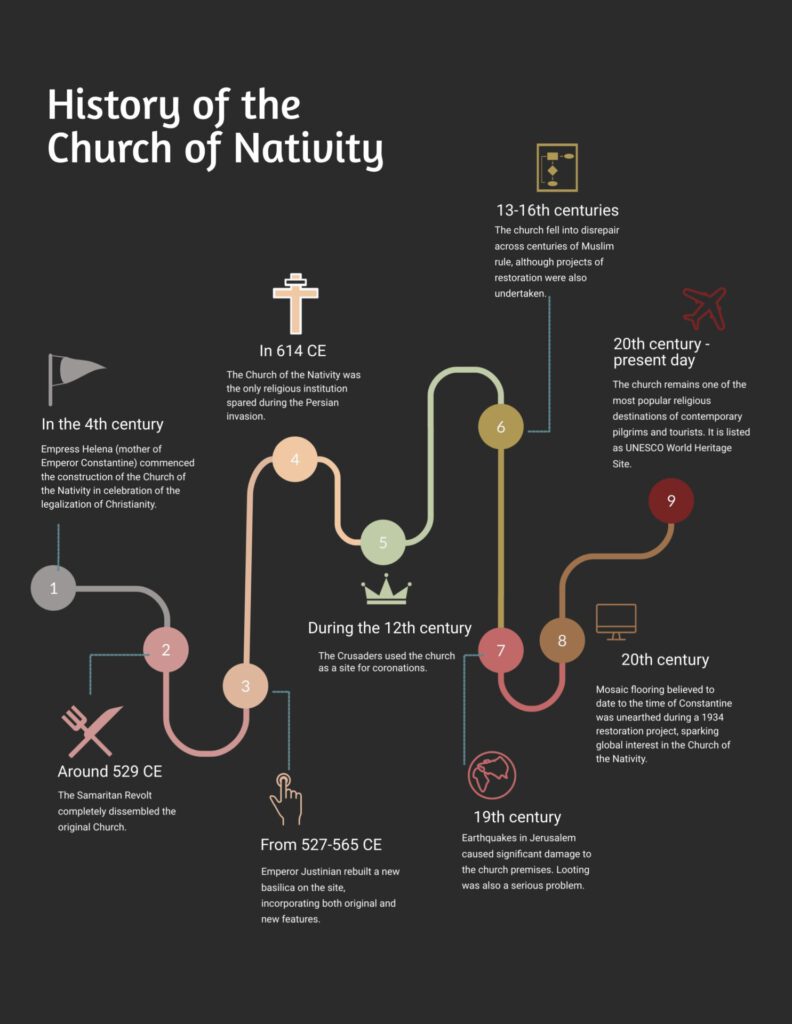

The Church of the Nativity, known in Middle Ages as the Church of Holy Mary or the Church of Our Lady, is significant because it marks the birthplace of the Messiah Jesus Christ.1 The Bible mentions that “now after Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea in the days of Herod the king, behold, wise men from the East came to Jerusalem” (Matthew 2:1) (Fig. 1).2 To commemorate Christ’s appearance on Earth, the Church of the Nativity was commissioned by Empress Helena, mother of the Roman Emperor Constantine who legalized Christianity in the fourth century. An anonymous Bordeaux pilgrim, who is generally considered to be the first Christian pilgrim to record his journey here, proved that the basilica had already been standing, under Constantine’s command of construction, at the time he visited the site in ca. 333 CE.3 Throughout the course of history, the Church of the Nativity has witnessed the rule of various religious parties, which has led to its frequent damage and reconstruction. Notable periods include the sixth-century destruction in the Samaritan Revolt and subsequent rebuilding under Emperor Justinian, and the turbulent Persian invasion in 614 CE.4 The outcome of these conflicts resulted in an interesting architectural fabric and style. Both textual and archaeological traces of the medieval site and pilgrims’ visits there provide us with clues for imagining the pilgrims’ experience at the Church of the Nativity.

Traces of History Inscribed in Stone

Located in Bethlehem, five miles south of Jerusalem, in Manger Square, the present-day church is a fortress-like structure with an absurdly small entrance—the so-called Door of Humility. Entering the Door of Humility requires today’s visitors to bend down or even kneel to enter the building’s interior. Over time, unorthodox interpretations have given the door the allegorical meaning of humbleness, enacted as a tangible, bodily reminder of the casting away of one’s egotistic pride and prejudice. It might be tempting for us to apply the same logic to medieval pilgrims, thinking that they, too, could have equated passing under this doorway to their wishes to seek redemption and cleanse their sins in the strong presence of Christ. That, however, would be an anachronistic, albeit romantic, reimagining of the past. The extant door is, in fact, post-medieval and was intended as a military defense system by the Ottoman Empire to prevent armed equestrian intruders from entering the church.5 Yet, from the church’s Justinian rebuilding through the better part of the Middle Ages, there were three fairly large post-and-lintel doors for pilgrims to enter, relatively comfortably and without the need to bow down, into the narthex.6 The cornice of the central entrance is still visible today, as are the faint outlines of a pointed arch that was sandwiched between the Justinian entrance and the extant Door of Humility (fig. 2). This pointed arch dates to the twelfth century and belongs to the extensive restoration project of the crusaders.7 As Jerome Murphy-O’Connor notes, this façade in itself “is a summary of the church’s history.”8 To the keen-eyed contemporary pilgrim or traveler, then, the miniature size of the doorway may not only evoke the later-acquired meaning of humility, but rather it can also be read as a microcosm of at least three periods in history. Now the stage is set—or shall we say the door is open—for us to enter the basilica (and the past).

Seeing through a Pilgrim’s Eyes

Before the latest restoration, which began in 2013, the Church of the Nativity’s interior might have seemed barren, and perhaps underwhelming for such a foundational site for the Christian faith (fig. 3).9 For decades before this restoration, the only glimpse visitors had of the earlier church came from the 1930s excavations, which revealed parts of a mosaic floor (fig. 4). That piece of pavement, a multi-colored and largely geometric composition, dated from the fourth century and belonged to the original Constantinian church.10 Along with the mosaic pavement, the first church also consisted of an octagonal apse that was directly above the Nativity Grotto, and a hole in the center of that apse offered a view of cave below.11 Although the Bordeaux pilgrim does not describe the interior decorations, we may imagine him, or his contemporary pilgrims, walking on the intricate mosaic designs, which survived the sixth-century fire and the Samaritan Revolt of 529.12

The Justinian rebuilding must have been—quite literally—like the phoenix that rose from the ashes. According to Eutychius of Alexandria, “The Emperor Justinian ordered his envoy to pull down the church of Bethlehem, which was a small one, and to build it again of such splendour, size and beauty that none even in the Holy City should surpass it.”13 His new church still kept the five-aisle plan of Constantine’s basilica, only he built an extra bay for the new narthex and altered the octagonal apse into a triapsidal form.14 Most of his church’s structure and plan survive to this day. Contemporary visitors still inhabit a similar architectural space as the Piacenza pilgrim (ca. 570), who called Bethlehem “a most impressive place,” and spoke at some length about the Nativity Grotto, which will be described below.15 We may never get a full picture of the interior decorations of the basilica in Justinian’s time, on the other hand. We know that it was covered, at least in part, with mosaics, as described in an anecdote that relates how this church survived the Persian invasion. According to this story, on their way to Palestine in 614, the Persian army pillaged and burned churches—but when they saw the mosaics over the door of the Church of the Nativity at Bethlehem depicting the magi in Persian dress, they spared the church.16 Given that Emperor Justinian seemed determined to build a church of marvelous “splendor, size and beauty,” we may, quite reasonably, envision an interior that was lavishly decorated with mosaics as well—in a similar way, perhaps, to that of its contemporary, the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna (fig. 5a-b).

Passing quickly through the years of Muslim rule—which our church also survived—we arrive at the Crusader period.17 Just as the building and rebuilding of the Church of the Nativity had found sponsors in Roman emperors, so too the church of this period have close royal connections to the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem established by the crusaders. Both Baldwin I (in 1100) and Baldwin II (in 1119) were crowned here, on Christmas Day no less, and the new redecoration project of the church was jointly sponsored by King Amalric of Jerusalem, Byzantine Emperor Manuel Komnenus, and Bishop Ralph of Bethlehem.18 As visitors can still see today, thanks to modern restorations, the ambitious program reflected the church’s royal ties and sacredness. As medieval pilgrims walked into the nave, they would have seen unfiltered sunlight shining through the clerestory windows, illuminating the interior space. The whole church would shimmer in gold as the sunlight glimmered off the golden mosaics (fig. 6).

A row of angels inhabit the spaces between the windows in the clerestory, seemingly floating in the light and watching over the pilgrims.19 Below the angels, mosaics of the Church Council, with the provincial councils on the north wall and ecumenical councils on the south, span the whole length of the nave.20 The east end of the church, which the angels point toward, might once have depicted the life of Christ, likely including site-specific scenes like the Nativity and Adoration of the Magi, even though this part of the mosaic is now lost.21 One can virtually picture pilgrims being astonished and overwhelmed with emotion the instant they stepped into the basilica. Given that medieval pilgrims had a severe lack of adequate transportation and obstacles posed unprecedented strain for them as they attempted to reach their destinations, successfully reaching a site like the Church of the Nativity would have held remarkable significance and reassured one’s faith.

After the fall of the Crusader Kingdom to Saladin in 1187, the Church of the Nativity did not have a smooth ride.22 The illustration below (fig. 7) depicts the grounds in approximately 1487, when parts of the church’s outer walls were left in ruins. Muslim rule did not seem to be enough deterrent, however, for the devout pilgrims who still wished to pay homage at the birthplace of Christ, despite their strenuous journeys . Christian services and activities were, in fact, not at a complete standstill in Bethlehem, and in the wider Holy Land, as we might presume. Some clerical and monastic activity, as well as pilgrimage traffic, continued intermittently.23 From 1347 onwards, the Franciscans started to represent the Western church at the Church of the Nativity on a regular basis, with some parts of the church under the management of Greek Orthodox and Armenian Christians.24 In point of fact, even as late as the early sixteenth century, pilgrims still flocked to Bethlehem, as the French monk Jean Thenaud did: “as soon as [Bethlehem] came into sight I was so filled with joy, comfort, and spiritual elation that all my past sufferings were forgotten.”25

Nativity Grotto: (“here is the root of the root . . . ”)

Medieval pilgrimages varied throughout the course of history, but the Nativity Grotto remained a pivotal sacred space within the premises of the Church of the Nativity. In the Bible, the birth of Christ is depicted as thus: “[Mary] gave birth to her firstborn Son, and wrapped Him in swaddling cloths, and laid Him in a manger, because there was no place for them in the inn” (Luke 2:7). In the present day, as it has been since the first Constantinian church, the Nativity Grotto is a crypt beneath the church’s stone-slab floor. The Nativity Altar (fig. 8a) is now adorned with opulent drapery, curtains, and embellished with silverware; beneath the altar, a fourteen-pointed silver star marks what is taken to be the birthplace of Christ (fig. 8b).26

There is no mention of that fourteen-pointed star in medieval sources, yet the cave still seemed to be a sensory feast for pilgrims at that time. The Piacenza pilgrim who visited the Justinian church, for instance, describes the grotto as “decorated with gold and silver; lamps within burning night and day.” According to Arculf, who also visited the Justinian church in ca. 680, “the whole of that cave of Bethlehem, with the Lord’s manger, is completely covered on the interior with precious marble.”28 Toward the later Middle Ages, aural stimuli seems to have played a significant part in pilgrims’ visits as well. Lisa Mahoney proposes that the bell towers that the crusaders added to the church would have created the “clarion sound [that] complemented material presence.”29 The Dominican friar Riccoldo da Monte di Croce (ca. 1243–1320) even witnessed a kind of mystery play commemorating the Nativity, and worship often was accompanied by anthems and hymns.30

Interestingly, the grotto is linked with a massive network of burial caves and underground passageways related to early saints and the Virgin. One account tells of pilgrims nearby reverently gathering soil, which was still white from the Milk Grotto (attributed to the Virgin Mary), ascribed as possessing divine power.31 Pilgrims also noted the many objects that reminded them of the Nativity in some manner or other, such as a rock with rings for tethering the animals to the manger, and a hole through which the star that guided the magi had purportedly disappeared.32 All these tales surely still provide vivid imaginative picture for contemporary viewers.

Afterword

Political turmoil and destruction seem to have long strained the site for worship, pilgrimage, and visits. Nonetheless, the Church of the Nativity is, for its many visitors, both a historical substantiation of Christ and a well-attended tourist destination in the new millennium. The latest restoration project that began in 2013 (see more in the video below) brought different religious communities together in the common desire to preserve this exceptional site of worship and pilgrimage. As one chapter of the Church of the Nativity draws to a close, there will always be another new beginning to come.

Watch the Short film by the Presidential Committee for the Restoration of the Nativity Church, documenting the ongoing restoration program begun in 2013.

Bibliography

Britt, Karen Christina. “Mosaics in the Byzantine Churches of Palestine: Innovation or Replication?” PhD diss., Indiana University, 2003.

Chareyron, Nicole. Pilgrims to Jerusalem in the Middle Ages. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005.

Cummings, E. E. “i carry your heart with me (i carry it in.” Poetry Foundation. Accessed May 1, 2020. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/49493/i-carry-your-heart-with-mei-carry-it-in.

Folda, Jaroslav. “Art in the Latin East: 1098–1291.” In The Oxford Illustrated History of The Crusades, edited by Jonathan Riley-Smith, 141–59. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Hunt, Lucy-Anne. “Art and Colonialism: The Mosaics of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem (1169) and the Problem of ‘Crusader’ Art.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 45 (1991): 78–81.

Jacobs, Andrew. “The Bordeaux Pilgrim (c. 333 C.E.).” Andrew Jacobs. Accessed April 18, 2020. http://andrewjacobs.org/translations/bordeaux.html.

———. “The Piacenza Pilgrim.” Andrew Jacobs. Accessed April 18, 2020. http://andrewjacobs.org/translations/piacenzapilgrim.html.

Mahoney, Lisa. “The Church of the Nativity and ‘Crusader’ Kingship.” In Crusading in Art, Thought and Will, edited by Matthew E. Parker, Ben Halliburton, and Anne Romine, 9–36. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2018.

Meehan, Denis, ed. “Adamnan’s De Locis Sanctis: An Electronic Edition.” UCC. Accessed April 15, 2020. http://research.ucc.ie/celt/document/T201090?segment=1#Chapter/toc.1.

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome. The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

O’Connor, Anne-Marie. “In Bethlehem’s Ancient Church, a Long Unseen Presence Appears.” National Geographic. May 27, 2016. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2016/05/Greeks-Geographic-exhibit-ancient-treasure-Agamemnon-Alexander-archaeology-museum/church-of-nativity-bethlehem-restoration-mosaics-angel/.

Pringle, Denys. The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: A Corpus, Volume I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Restoration of the Church of The Nativity. Accessed May 1, 2020. https://www.nativityrestoration.ps/.

Runciman, Steven. A History of the Crusades, Volume 1: The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1951.

Shomali, Qustandi. “Church of the Nativity, History & Structure.” Proceedings of the International Congress More than Two Thousand Years in the History of Architecture. Paris: UNESCO, 2003.The English Standard Version. Accessed May 1, 2020. https://www.esv.org/Matthew+2/.

Image Credits

Header image: The Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem, West Bank, Palestine, Israel. Photograph taken by Neil Ward, August 2, 2012. Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church_of_the_Nativity#/media/File:Church_of_the_Nativity_(7703592746).jpg, licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Timeline: “History of the Church of the Nativity” by Pinky Tsang.

Fig. 1 Scene of the Nativity, part of the decoration on the underside of the lid of The Fieschi Morgan Staurotheke (reliquary of the True Cross), Byzantine, early 9th century, niello, collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/472562?searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&showOnly=openAccess&ft=nativity&offset=60&rpp=20&pos=79. Modified image in the public domain.

Fig. 2 “Door of Humility”. Photograph taken by Sek Keung Lo, February 10, 2011. Source: Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/7411596@N08/5485778792. Licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Fig. 3 Photograph of the central nave of the Church of the Nativity, facing the apse, taken between 1934-1939. Source: “Interior of Church of Nativity showing barrel of blessed water on Epiphany day,” United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division (digital ID matpc.04155), http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/matpc.04155/. Public domain.

Fig. 4 Original Mosaic Floor of the Church of the Nativity from the Time of Constantine. Photograph taken by Wknight94, February 5, 2010. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Church_of_the_Nativity_mosaic_floor_2010_2.jpg, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Fig. 5a The presbytery, Basilica of San Vitale. Photograph by Tango7174, created on September 19, 2007. Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Emilia_Ravenna5_tango7174.jpg. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Fig. 5b Emperor Justinian and his retinue, Basilica of San Vitale. Photograph by Roger Culos, created on October 5, 2015. Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basilica_of_San_Vitale#/media/File:Sanvitale03.jpg. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Fig. 6 North nave. Photograph by discoste, taken on November 15, 2008. Source: Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/48589011@N00/3069194014. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Fig. 7 Illustration from Konrad von Grünenberg’s Beschreibung der Reise von Konstanz nach Jerusalem (Description of the Journey from Constance to Jerusalem), 1487, f.47r. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Beschreibung_der_Reise_von_Konstanz_nach_Jerusalem#/media/File:Konrad_von_Gr%C3%BCnenberg_-_Beschreibung_der_Reise_von_Konstanz_nach_Jerusalem_-_Blatt_47r_-_099.jpg. Public domain.

Fig. 8a The Altar of Nativity within the Nativity Grotto, the Church of the Nativity. Photograph taken by Rossnixon, January 17, 2001. Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church_of_the_Nativity#/media/File:Birthplace_of_Jesus.jpg. Public domain.

Fig. 8b Detail of the 14-pointed star. Photograph taken by Mark87, March 30, 2007. Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church_of_the_Nativity#/media/File:Nativity_Grotto_Star.jpg. Public domain.

The Author

Pinky Tsang is a very modern student writing about “unmodern” times.