The Humans That Lurk in the Dark: Others and Othering in Medieval Pilgrimage

Introduction

While general notions of race in the modern era appear to be highly fixed, it was not always this way. Race has not always been something that could be determined at first glance. Medieval race as explored in this post, was a somewhat flexible thing.

Medieval Race and Modernity

It is easy to believe that this type of racial flexibility was one lost to time. Yet when Irish immigrants began entering the US en masse, they were originally seen as lesser than the pre-existing white American populations. America was a Protestant nation, and Irish Catholicism did not fit the mold of whiteness set by Americans at the time. In order to become white, says Noel Ignatev, the Irish had to “learn to subordinate county, religious, or national animosities…to a new solidarity based on color.”1 In order for Irish people to assimilate, in order for them to become Americans in the eyes of the people, they first had to become “pure.” This happened again, though the assimilation was not successful, in the 1940’s. In Moustafa Bayoumi’s Racing Religion he presents the argument that: “Religion determines race. At least in 1942 it did, and so Arabs were not considered white people by statute because they were (unassimilable) Muslims.”2 Bayoumi asks the reader to understand the category of racialized religion as it relates to assimilation, not just to a racial category, but to a religious category. To be seen as white, one must be both “phenotypically white” as well as “religiously white,” and the loss of one of these traits would be enough to disallow a person the status of whiteness and/or inherent purity. Hence why Muslims in this case are not perceived as “white” by a majority of Americans.

Notions of humanity have always been powerful tools for those looking to oppress others. So-called “races,” whether Plinian, medieval, or modern, are all socially constructed concepts. Examining the tympanum at Vézelay reminds us of this fact. The idea of race as something beyond a “phenotype” is not new. Furthermore, it reminds us that constructing races to aid in the power structure of the church or state is not something that happens only in the modern age. The tools of power are ancient ones. Yet, now we have a choice, we can reexamine our notions of race, our notions of how we understand each other. We do not have to make animals out of our differences, much less monsters.

On Vézelay

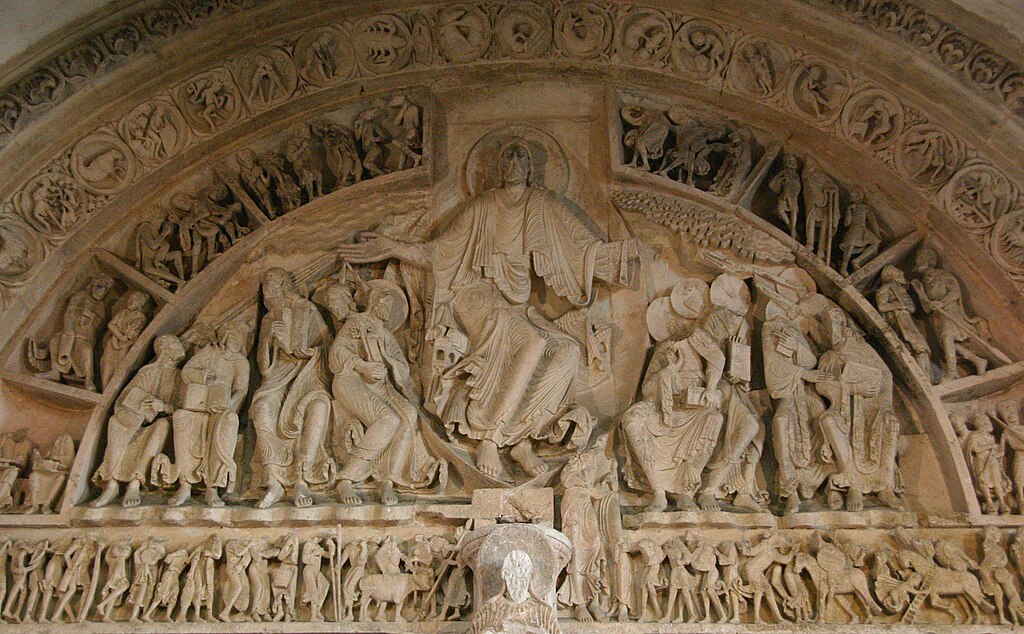

The Church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine was caught up in several socio-political conflicts while it was being constructed. It was originally a monastery for women circa 858, then it was destroyed by Normans in 873 and re-founded as a monastery for men in 878.3 In the years between 878 and 1050, the monastery claimed ownership of a relic of Mary Magdalene, thus making the church a major destination for pilgrims.4 Vézelay was also a popular starting point for travelers on the Camino de Santiago de Compostela. However, the traffic produced by this pilgrimage caused unrest amongst the locals, both secular and religious, and led to a series of conflicts between them regarding the building. The church caught fire in 1120, killing several pilgrims, and an elaborate narthex with three carved portals was built during the reconstruction of the church. The church was consecrated in 1158.5

Within the arches of the narthex we find various depictions of pilgrims, some human, some who appear like man-animal hybrids, and some who appear fully inhuman. These “other” pilgrims are creatures derived from the Plinian Races, and they present an interesting question for both modern and medieval viewers. The portal and the central tympanum were built after 1120, meaning pilgrimage was common for people of the day, but pilgrims likely had not begun journeying to Vézelay en masse.6 This suggests that the sculptors of the portal believed that Vézelay would rise to prominence as a site for pilgrimage before it did and that the motif of the pilgrims was inspirational, not representational. If this is true—why select the specific “others” that were chosen?

Thus, the primary question of this article: What makes someone human in the medieval mind, and what makes someone inhuman?

Explore below this interactive Map of Medieval Others, created by the author. Feel free to zoom in and out and drag the map around. Click on the top-left icon to show the legends, and click on each pin marker to show descriptions. Click on the top-right icon to explore the map in a new tab.

On “Race”

The term “race” itself is contentious among modern scholars of the subject, both in its definition and its utility. Combined with the label “monstrous,” the modern mind is primed to read these descriptions of the other as one of two things: One—a non-human entity from the medieval imagination, or Two—a human entity being detected as non-human, a racist caricature of (typically) nonwhite bodies. However, according to Asa Simon Mittman:7

(…) we should reject the term because its retention reifies the implicit reality of the ‘white’ or ‘European’ or ‘Christian’ ‘race’ at the core of medieval discourse. Whenever we write ‘monstrous race,’ we accept ‘Christendom’s’ rhetoric of its own existence, and we imply the presence of a ‘normal’ or ‘normative race’ at the center, revealed by these ‘monstrous races’ at the periphery.

While grappling with this discourse, this article will endeavor to utilize the term “Other” over “Race” as to both separate the modern and medieval context, as well as attempt to practice the antinormativity Mittman describes. This is primarily an attempt to retain the theoretical humanity of the figures depicted. While they appear different from traditional understandings of humanity, they are still based upon the body/form of the human species. To regard them as “monstrous races” implies that groups other than White/Christian are inherently inhuman and fall back into the normative pattern Mittman describes.8

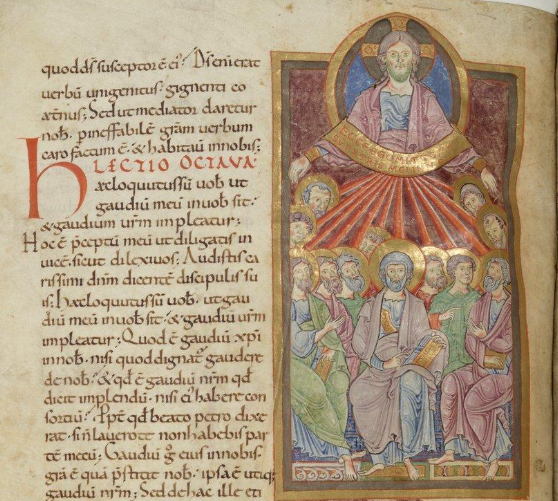

The Pentecost and Other Imagery

The Monstrous Races by John Block Friedman, a text on medieval conceptualizations of race across disciplines including the arts, provides our beginning. Here, he lays out a veritable dictionary of the Plinian races; one such notable entry is the “Cynocephali” (“dog-head”).9 Among the most popular of the races are the Dog-Heads, who, according to Ctesias, “live in the mountains of India.”10 Friedman gives us varied medieval depictions (produced from the eighth to the fifteenth century) of men or creatures taken from the same source as the Cynocephali. Additionally, he establishes that the Cynocephali were most often targets for conversion, and seen frequently in scenes of the Pentecost. In medieval Christianity, it was thought that through conversion to Christianity, some of these “non-humans” were able to regain or “earn” their humanity.11 If this is true, it indicates that the tympanum at Vézelay has more to tell us about medieval race than just how it is (hierarchically) organized. It tells us that the medieval race was less concrete than we see it currently, and that for those who devoted their life to religion, it may have been possible to transcend race and the boundaries of humanity itself. As Paul Freedman states: “The existence of peoples bordering on the non-human provoked questions about why they were created…or might be converted to Christianity. …[T]heir relation to the ultimate purpose of the secular order differentiated the medieval monstrous races from their classical counterparts.”12 In essence, the context of these hybrid creatures, specifically on the central tympanum at Vézelay, changes their meaning. To understand what these hybrid creatures are doing and what they communicate at Vézelay, we must understand how they work more broadly in medieval Christian contexts.

It is particularly significant that the sculptors chose to use scenes of the Pentecost for this tympanum. The Pentecost is a biblical story in which the Holy Spirit comes to the apostles and blesses them with the ability to speak the languages of the world, allowing them to preach the word of God to all people. Interestingly, the Gospel of Mark proclaims that it is a holy duty to preach the word of God to “every creature.”13 This distinction between “creature” and “people” further complicates the tympanum because it calls into question the nature of these hybrid forms. Are they the people of the Pentecost, just people from other nations that God has created, or are they creatures decidedly worthy of God but not afforded the same sentience and identity? If medieval race is a mutable condition rather than a permanent one, choosing to sculpt these others in their “sinful” forms vs. their “pure” forms asks the viewer to once again dichotomize the world around them. They are either pure or sinful and, therefore, human or non-human.

While the Pentecost is traditionally a joyful scene, Adolf Katzenellenbogen challenges this “welcoming” narrative. Discussing in particular the apocalyptic prophecies of Isaiah, he points out that the Pentecost can also be read as an apocalypse, as the bible states that the people of the world will convert to Christ at the end of times.14 This creates another interesting dimension for the pilgrims as they traverse the Camino de Santiago or other pilgrimages. Did they see their foreign counterparts as equals or as signs of the end times? According to Nahir I. Otaño Gracia and Daniel Armenti:15

The existence of these categories [white and non-white] creates a foundation for an ideology of racism between a ‘European’ nature and an ‘Other’ nature: the former is superior to the latter in the hierarchy of virtues.

This hierarchy of virtue closely relates to Katzenellenbogen’s reading of the procession at the Pentecost. The white and “pure” are given visual importance through their central placement, but they are also given another sort of status—their humanity. In choosing to depict other humans as inhuman creatures, the medieval viewer is asked to assign themself one of two categories: human or not. Katzenellenbogen states: “These different classes of humanity are arranged in hierarchical order. The lowest classes form the end of two processions, at the extreme left the hunters, at the extreme right the savages. The highest classes, the priests and the soldiers, are afforded the favored places at the heads of the procession.”16 Importantly, Debra Higgs-Strickland reminds us that: “For medieval Christians, the monstrous races tradition…received its ultimate authority from the Genesis account of the aftermath of the flood, which describes the propagation of humanity from Noah’s three sons.”17 These monstrous races then begin like us—human. In the Christian mind, it is when they turn away from God they are rendered into these strange and non-human creatures. With the previously discussed notions of medial race in mind, the hierarchies of humanity feel especially potent. It is a stark reminder that even if one could achieve “purity” in the eyes of God, it does not necessarily mean that humans believed that you were worthy of respect or dignity. You then had to exist within the same power scale as the rest of humanity. To even be human is a hierarchical category in itself, and then the circumstances of humanity will dictate your importance to other humans.

Vézelay and Beyond

Greta Austin when discussing the Wonders of the East, provides us an interesting insight into the medieval mind regarding race stating: “In the Wonders, however, the human body could be shaded by relative degrees of ‘humanity’ and ‘bestiality.’”18 and later, “I believe that Wonders was interested in other peoples in order to represent, in pictures as in words, the order and diversity of those to whom God offers his salvific grace.”19 Wonders itself can be found in a few extant manuscripts, all dating back to around the 11th/12th century thus placing this type of thinking chronologically in line with Vézelay.20 Beyond that, it provides us an additional temporal and geographical source for these hybrid creatures, this type of figural imagery was not solely isolated to Vézelay, or even France. This type of hierarchical organization of the non/semihuman appears across medieval landscapes and minds. Humanity and nonhumanity are not two entirely disparate concepts, they exist on a spectrum, just as morality or purity might. Thus for pilgrims, the concept of the other/race, would have shifted as the ideas of “purity” did.

Bibliography

Ashcraft, W. Michael. “Review: The Ashgate Research Companion to Monsters and the Monstrous Edited by Asa Simon Mittman with Peter J. Dendle.” Nova Religio 20, no. 1 (2016): 107–108. https://doi.org/10.1525/novo.2016.20.1.107.

Barbato, Mariano. “Power through Pilgrimage: The Making of the Papacy.” In Power of the Priests, edited by Sabine Kubisch and Hilmar Klinkott, 215–30. Berlin and Boston: Walter de GruyterGmbH, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110676327-012.

Bayoumi, Moustafa. “Racing Religion,” CR: The New Centennial Review 6, no. 2 (Fall 2006): 269, https://doi.org/10.1353/ncr.2007.0000.

Caswell, Helen Rayburn. The Parable of the Sower. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1991.

Connell, Charles W. “Foreigners and Fear in the Middle Ages.” In Handbook of Medieval Culture: Fundamental Aspects and Conditions of the European Middle Ages, vol. 1, edited by Albrecht Classen. Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110267303-025.

Feldman, Judy Scott. “The Narthex Portal at Vézelay: Art and Monastic Self-Image.” PhD diss.: The University of Texas at Austin, 1986. http://libproxy.vassar.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/narthex-portal-at-Vézelay-art-monastic-self-image/docview/303438000/se-2.

Friedman, John Block. The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2007.

Gracia, Nahir I. Otaño, and Daniel Armenti. “Constructing Prejudice in the Middle Ages and the Repercussions of Racism Today.” Medieval Feminist Forum: A Journal of Gender and Sexuality 53, No. 1 (2017): 187-88. http://dx.doi.org/10.17077/1536-8742.2093.

Higgs-Strickland, Debra. “Monstrosity and Race in the Late Middle Ages.” In The Ashgate Research Companion to Monsters and the Monstrous, edited by Asa Simon Mittman and Peter J. Dendle, 365-87. Surrey and Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2012.

Horner, Ralph C. Pentecost. Brockville, Ont.: Henderson Printing, 1993.

Ignatiev, Noel. How the Irish Became White. London: Routledge, 2015.

Jones, Timothy S., and David A. Sprunger, eds. Marvels, Monsters, and Miracles : Studies in the Medieval and Early Modern Imaginations. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 2002.

Katzenellenbogen, Adolf. “The Central Tympanum at Vézelay: Its Encyclopedic Meaning and Its Relation to the First Crusade.” The Art Bulletin 26, no. 3 (1944): 141–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/3046949.

Kempe, Margery. The Book of Margery Kempe: A New Translation, Contexts, Criticism. Edited and translated by Lynn Staley. New York: W.W. Norton, 2001.

Kim, Susan M., and Asa Simon Mittman. “Monstrous Iconography.” In The Routledge Companion to Medieval Iconography, edited by Colum Hourihane, 518-33. New York: Routledge, 2017.

Low, Peter. “‘You Who Once Were Far Off’: Enlivening Scripture in the Main Portal at Vézelay.” The Art Bulletin 85, no. 3 (2003): 469-489. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2003.10787086.

Mittman, Asa Simon. “Are the ‘Monstrous Races’ Races?” postmedieval 6, no. 1 (Spring 2015): 36–51. http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/gnqd-tg94.

Morehead, John W. “Michael E. Heyes, ed., Holy Monsters, Sacred Grotesques: Monstrosity and Religion in Europe and the United States.” Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts 31 (1): 140-143, 169. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/holy-monsters-sacred-grotesques-monstrosity/docview/2537700623/se-2.

O’Malley, Patrick R. “Irish Whiteness and the Nineteenth-Century Construction of Race.” Victorian Literature and Culture 51, no. 2 (2023): 167-98. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1060150322000067.

Rudolph, Conrad. “Macro/Microcosm at Vézelay: The Narthex Portal and Non-elite Participation in Elite Spirituality.” Speculum 96, no. 3 (2021): 601-661. https://doi.org/10.1086/714579.

Whitaker, Cord J., Nahir I. Otaño Gracia, and François-Xavier Fauvelle. “Speculum Themed Issue: ‘Race, Race-Thinking, and Identity in the Global Middle Ages’.” Speculum 99, no. 2 (2024): 321-330. https://doi.org/10.1086/729426.

Zeringue, Christine Ann, “Evaluation of the central narthex portal at Sainte-Madeleine de Vèzelay”. Master’s Theses, Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, 2005. https://repository.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/85.

Image Credits

Header Image. Detail of the central tympanum at the church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine, Vézelay, ca. 1120-1130s, showing right uppermost compartment on the archivolt. Photograph by user “Gaudry daniel”, August 9, 2012. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vezelay_narthex_central10.jpg. Cropped image licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 Deed.

Fig. 1. Central tympanum of the Church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine, Vézelay, ca. 1120-1130s. Photograph by Gerd Eichmann, September 20, 2008. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:V%C3%A9zelay-Sainte-Marie-Madeleine-122-Tympanon_innen-2008-gje.jpg. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 Deed.

Figs. 2. Detail of the central tympanum of the Church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine, right of lintel. Photograph by user “Gaudry daniel”, August 9, 2012. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vezelay_narthex_central_1.jpg. Cropped image licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 Deed.

Fig. 3. Detail of the central tympanum at the church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine, showing the left uppermost compartment on the archivolt. Photograph by user “Ibex73”, August 7, 2019. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tympan_du_narthex_de_la_basilique_de_V%C3%A9zelay_(d%C3%A9tails)_(14).jpg. Cropped image licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 Deed.

Fig. 4. Detail of the central tympanum at the church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine, showing right uppermost compartment on the archivolt. Photograph by user “Gaudry daniel”, August 9, 2012. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vezelay_narthex_central10.jpg. Cropped image licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 Deed.

Fig. 5. A cynocephalus, detail from a photographic reproduction of a copy of the “Nuremberg Chronicle”, 1493, fol. 12r. Photograph by user “Mattes” / Beloit College, August 10, 2006. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Schedel%27sche_Weltchronik-Dog_head.jpg. Public Domain.

Fig. 6. Illuminated miniature of the Pentecost, from the “Lectionnaire de Cluny”, ca. 1100, fol. 79v, Bibliothèque nationale de France. Source: Gallica Digital Library, Bibliothèque nationale de France / Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lectionnaire_de_Cluny_-_BNF_NAL2246_f79v.jpeg. Public Domain.

The Author

Eva Martinez is a student of Religion and Medieval/Renaissance Studies at Vassar College. They are fascinated by all things Medieval, and are particularly interested in how modern and medieval religion/culture intersect.